A fascinating presentation at the October 2024 Australian International Education Conference (AIEC), “Global student flows: understanding the ‘next’ wave in international education,” showcased data-based forecasts for international student mobility for the rest of the decade.

Gabrielle Rolan, pro vice chancellor at the University of South Australia, led the event, which featured senior Navitas Australia executives Jonathan Chew (chief insights officer) and Ethan Fogarty (senior manager, government relations) sharing Navitas’ projections. Those projections were based on a variety of primary and secondary inputs from Oxford Economics and UNESCO.

International student mobility set to grow

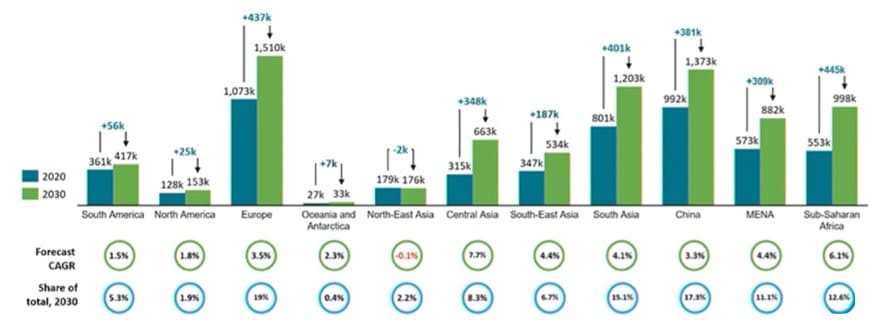

In 2019, six million students were studying in countries other than their own. Navitas projects 4% growth over the next few years, culminating in just over nine million students abroad by 2030.

India and China will continue to send the most students, followed by Nigeria. Regionally, Central Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa are expected to post the most percentage growth.

Will India overtake China?

The question is on everyone’s minds. Indian student demand for study abroad has been extraordinarily high for several years, while Chinese demand has been more complicated – slowed by the pandemic and disrupted by the proliferation of high-quality domestic options.

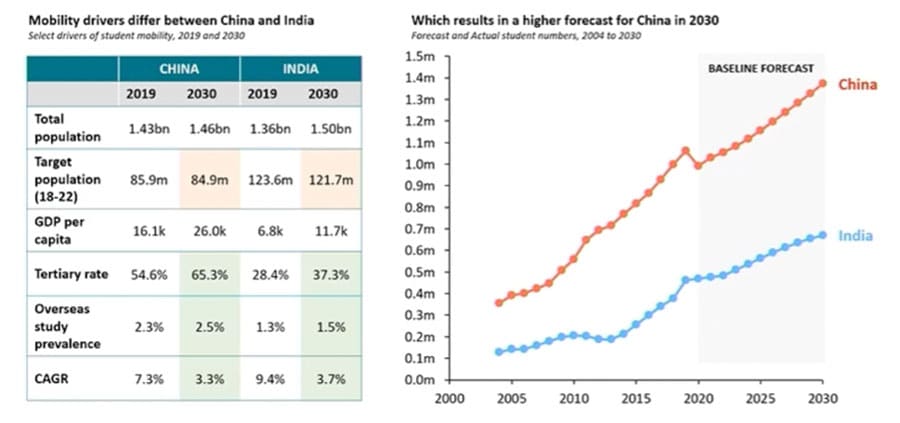

Mr Fogarty crystallised the complex interplay of factors that might inform the answer. India’s overall population will exceed China’s in 2030, as will its number of 18–22-year-olds. These dynamics guarantee an upward outbound mobility trajectory.

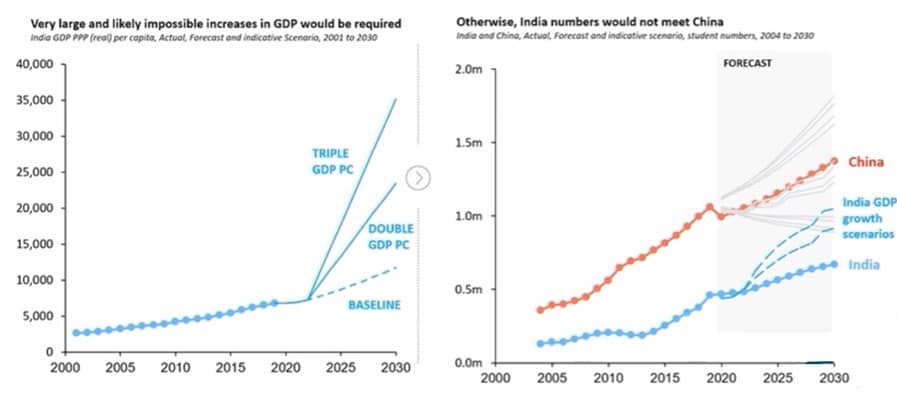

However, India trails China in several ways that will affect how many of its students will study abroad in the next few years. Its tertiary enrolment ratio, outbound study mobility ratio, and GDP per capital are much lower than China’s. These factors lead to a lower projected outbound volume in 2023 than China’s.

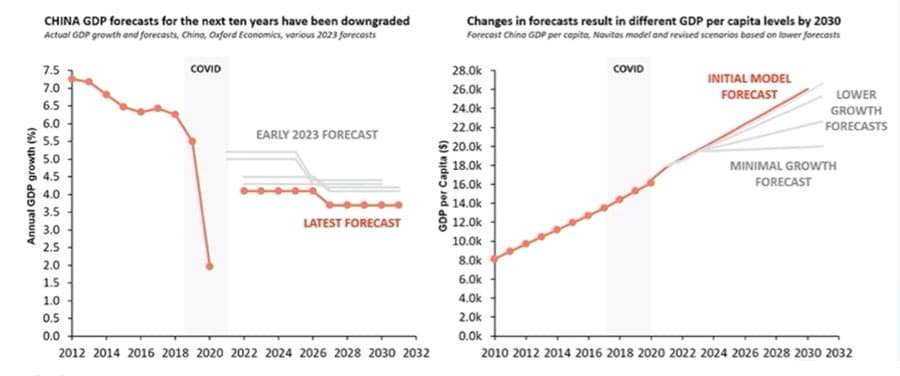

Still, for China, the outlook is uncertain. Mr Fogarty notes that confidence in the Chinese economy has deteriorated since the pandemic. Predictions for Chinese outbound have been volatile as a result, as shown in the following chart.

Mr Fogarty foresees “countervailing” inputs that will determine what happens in the event China’s economy deteriorates:

- On the one hand, affordability would become more of an issue – fewer families might be able to send their children for study abroad;

- On the other, unemployment and limited job prospects would drive more Chinese students to pursue opportunities in other countries.

Mr Fogarty points out: “Poor employment prospects can actually drive positive effects for students’ propensity to study.”

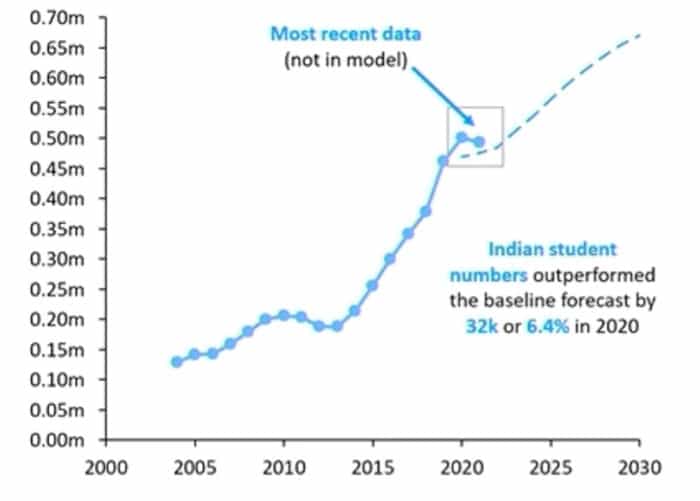

Because of this uncertainty, it is not impossible that India will defy the forecast and edge ahead of China by 2030. India has outperformed Navitas’ forecasts in the past, and it was instrumental to the recovery of international education sectors in leading destinations post-COVID.

But India would a great deal of catch-up in the next few years to match the market fundamentals of China. As shown below, GDP per capita would need to move from 6.8K in 2019 to 35K in 2030. Tertiary enrolment would have to jump from 28.4% to 58%. And there would need to be a doubling of the outbound student mobility ratio.

The more likely scenario – if India were to outpace China – would be more compelling “pull” factors for Indian students, such as better post-study work and immigration opportunities.

Whatever happens, it is almost certain that China and India will remain the top two sending markets in 2030.

A narrower pool of students

New immigration settings in leading destinations are fundamentally changing the way (1) international students consider study abroad, (2) educators recruit overseas. The following chart succinctly summarises this shift for Australia, but it could easily be extrapolated to the other three of the Big Four: Canada, the UK, and the US. Incoming students will be more academically motivated and less price-sensitive.

This isn’t to say that demand for foreign qualifications in emerging markets will lessen. To the contrary, it will probably grow. But transnational education, including branch campuses, international exchanges, and models where students complete part of their degree at home and part abroad, will likely play a much larger role in expanding access to globally recognised degrees in the future.

For additional background, please see:

Source