The Chinese government is again reporting on youth unemployment rates after have suspending such data releases for the past several months – but now using a revised method that excludes students from the data. The news is not great: the National Bureau of Statistics found that the jobless rate for 16-24-year-olds rose to 18.8% in August 2024, up nearly two percentage points compared with July, when it was 17.1%. These are historically high rates of unemployment for the college-aged cohort in China.

There are rising numbers of jobless Chinese between the ages of 25 and 29, as well. For this age bracket, the rate was 6.9% in August, up from 6.5% in July.

Faced with limited prospects and a faltering economy, many young Chinese are choosing to keep studying rather than try to find a job. This is reflected in the fact that top Chinese universities are reporting more graduate than undergraduate enrolments. At top-ranked Tsinghua University, for example, there were 3,800 new undergraduates admitted in September versus 9,925 postgraduates.

Some Chinese who opt to keep studying will find spots in Chinese universities, while others will look abroad. But the average Chinese student-consumer looks different than in the past, less buoyed and confident given the relatively sluggish Chinese economy and more willing to look beyond elite educational brands. As we reported in July 2024, there is sometimes a misconception among foreign educators that many Chinese families can still readily fund study abroad to the same extent they have in the past. The reality is more complicated.

Slowdown is an adjustment for Chinese consumers

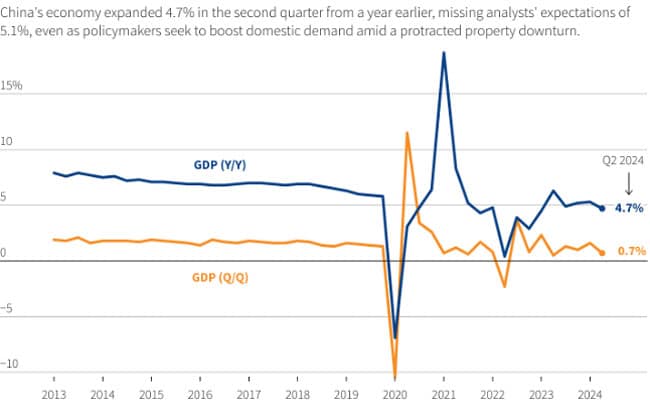

China is the world’s second-largest economy and had set a modest growth target of 5% for 2024. Analysts now expect this target to be missed. The economy grew by 4.7% between April and June 2024

At the root of the issue is an extended property downturn, deflationary pressures affecting the retail sector, and stagnant salary levels. China’s manufacturing output is relatively stable, but domestic consumer demand is weakening as consumers put more of their money into savings. In February 2024, the consumer savings rate hit an all-time high – at the same time as consumer confidence came close to an all-time low.

Lynn Song, chief economist for Greater China at ING, told Reuters:

“A negative wealth effect from falling property and stock prices, as well as low wage growth amid various industries’ cost cutting is dragging consumption and causing a pivot from big ticket purchases toward the basic ‘eat, drink and play’ theme consumption.”

Speaking with NBC News, Wang Ran, a 27-year-old designer, said she was changing her spending habits:

“[Before] I pretty much bought things whenever I saw something I liked. But this year, I might have to consider the financial aspect a bit more.”

The Chinese middle class ballooned from 3% of the population in 2000 to over half in 2018, according to the Pew Research Centre. Given China’s huge population (1.4 billion), that’s a lot of middle-class citizens feeling the pinch of a tougher job market and an economic downturn.

Youth anxiety is easily spotted in China these days, says NBC News:

“On social media, users share hacks to save money. Public libraries are filled with working-age people who are searching job sites and polishing résumés or who just need somewhere to go.

Young urban professionals also appear to be driving a surge in sales of lottery tickets, which reached a record 580 billion yuan ($80 billion) last year, according to data from the Finance Ministry. About 85% of purchasers were ages 18 to 34, compared with about 55% in 2020, the Chinese research firm MobTech reported.”

Value for money replaces fixation on luxury brands for many

A trend known as “reverse consumption” – which involves prioritising value for money over brand name – is taking hold in China. This is a marked change from the obsession with luxury brands that we saw in the years of China’s rapid economic expansion. Young people are driving the trend.

Jie Zhou, writing for PayXert, a payment services provider, says that reverse consumption is not a “consumption downgrade.” She says:

“Consumption downgrading typically involves reducing spending and opting for lower-quality and more affordable products. In contrast, reverse consumption takes a different approach. It aims to maximise happiness while minimising expenditure. This approach also values personal taste and individuality, with consumers willing to invest in unique designs and experiences.”

Ms Zhou advises foreign brands to understand the evolving mindset of Chinese youth. She said, “reverse consumption and evolving consumer behaviour pose new challenges like declining sales … however, they also offer opportunities for enhancing competitiveness and fostering sustainable development.”

Specifically, she adds:

“Businesses can better adapt by focusing on the following:

• Cost-effectiveness & competitiveness: Chinese consumers tend to more and more prioritise quality and cost-effectiveness over brand names. Brands should understand competitors’ offerings and optimise their sales strategies, particularly in terms of price/performance.

• Brand value & social responsibility: Consumers now seek brands with meaningful philosophies, social responsibility, and sustainability practices.

• Personalisation & differentiation: Tailored products and services appeal to Chinese consumers, especially youth.”

Western institutions face increasing competition from Asian universities

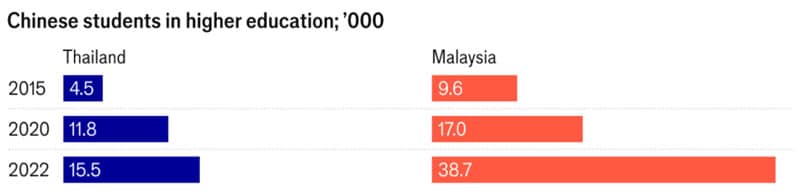

We have reported in the past couple of years about Chinese families’ increasing price-sensitivity regarding study abroad, and their consequent interest in more affordable destinations such as Thailand.

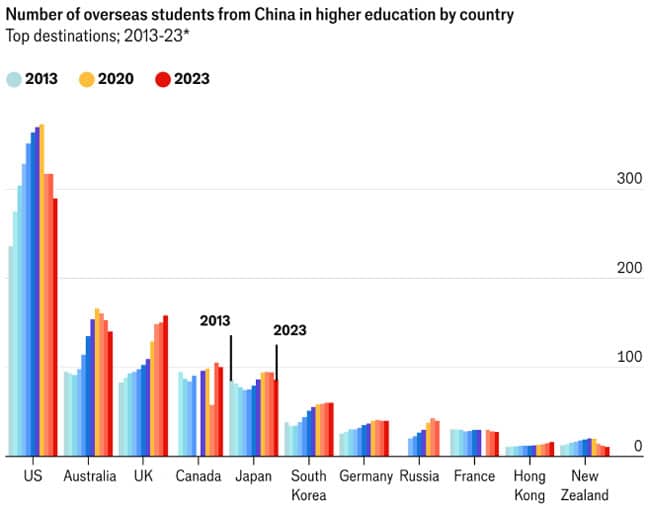

The Economist Intelligence Unit also explored this trend in July 2024, providing a chart that illustrates declining Chinese enrolment trends in Western destinations other than the UK and another chart that shows growing Chinese demand for study in Asia.

Show me the money

No matter where an institution is – North America, Europe, or Asia – it will have to prove its programmes lead to positive job outcomes, in China or elsewhere.

Su Su, senior project consultant at BONARD’s China branch, said in a webinar earlier this year that:

“The so-called return-on-investment is a term I hear mentioned more and more by parents and students when planning overseas studies. Parents will consider affordability and employability when choosing a school and will appreciate internship opportunities in local companies.”

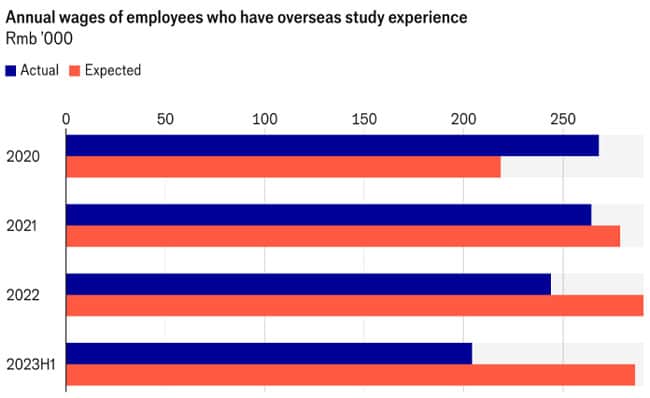

There is a growing feeling in China that study abroad may not provide the ROI that families are looking for. The Economist adds:

“The allure of overseas study derives principally from the ability to secure a higher income through a foreign education. However, this has become less true over the years, as the actual average income of those who have overseas experience has been declining. In addition, students who return to China tend to find work in sectors such as information technology and finance, which have been facing crackdowns from the Chinese authorities in recent years, considerably limiting their wage growth. Chinese students may also avoid overseas experience if they want to get into the civil service system, amid the intensifying anti-espionage movement in China.”

Key takeaways

It is going to take more to recruit Chinese students now than in the past – even now, when many Chinese students are choosing to continue to study rather seek a job. The idea that Chinese students are rich and driven purely by rankings and prestige is outdated – the market is much more complex than that going into 2025.

Careful, targeted strategies based on current market intelligence are needed. Chinese regions and cities offer varying levels of opportunity. What works in one area may not work in another. Be prepared to lead with graduate outcomes, internships, career services, and scholarships. It’s a new day in China, and students there are more savvy, cautious, and complex in their decision-making about study abroad.

For additional background, please see:

Source