by Rev. Dorothy S. Boulware

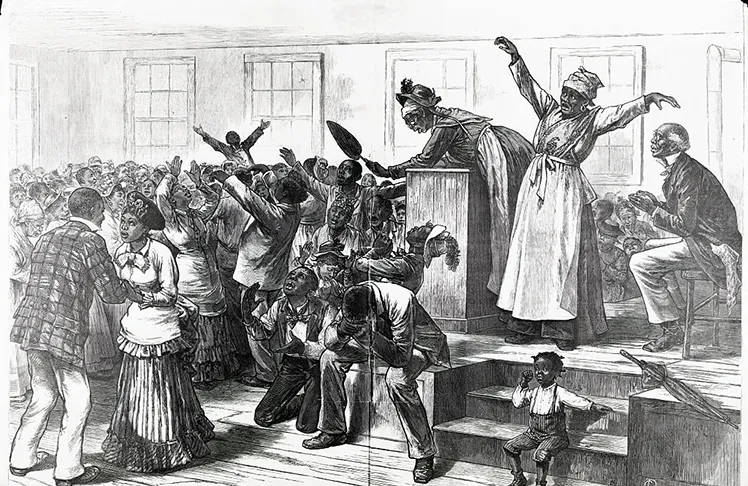

On Dec. 31, 1862, cloaked by what likely was a cold, dark night in the dead of winter, groups of Americans of African descent — some free, others still enslaved — gathered together in secret. As a bloody war over their place in the nation raged, the African Americans took part in an age-old religious tradition of Wesleyan origin, marking the end of one calendar year and the beginning of another with prayer and reflection.

Instead of somber reflection on past sins and prayers to God for obedience and grace, however, the Black men, women, and children who huddled in dank cellars, in ramshackle slave quarters, or outdoors under the stars, waited anxiously as midnight slowly approached, when the Emancipation Proclamation would take effect — marking what they hoped would be freedom for themselves and their loved ones.

Most people in the Black community are familiar with Watch Night, one of the oldest cultural traditions of New Year’s Eve. Marked with late-night worship services in church, the event is usually followed by a fellowship meal or a love feast.

The great demonstrations of faith do not belie the remnants of superstition imported along with the ancestors. One is that a man had to walk through the entire house before any residents, especially women, to ward off any bad luck for the incoming year.

Another is the selection of particular foods to accentuate the meals: collard greens to assure the influx of money and black-eyed peas with rice — hoppin’ John— also for good luck.

Black people adopted Watch Night and made it their own.

But the history of Watch Night is one of contradictions.

Even in 1862, celebrated in secret, Watch Night was a time of celebration of the faithfulness of God, his goodness and his grace — a strange sentiment for people stolen from their homeland and held against their will in chattel slavery. Although some elements have been altered by time and necessity, the tradition prevails in the Black community, regardless of war or hard times.

Modeled after the New Year’s Eve service begun by the Moravians, a 18th-century religious sect, and incorporated into Protestant worship by Methodist theologian Rev. John Wesley, Black people adopted Watch Night and made it their own. Along with religious gratitude, they transformed it into an expression of gratitude, overlaid with anticipation of freedom and high hopes for their future.

According to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the first Watch Night took place during the height of the Civil War.

“On the night of December 31, 1862, enslaved and free African Americans gathered, many in secret, to ring in the new year and await news that the Emancipation Proclamation had taken effect,” according to the museum’s website. “Just a few months earlier, on September 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued the executive order that declared enslaved people in the rebelling Confederate States legally free.”

“However, the decree would not take effect until the clock struck midnight at the start of the new year,” according to the NMAAHC. “The occasion, known as Watch Night or ‘Freedom’s Eve,’ marks when African Americans across the country watched and waited for the news of freedom.”

Watchman, watchman, please tell me the hour of the night.

The nature of Watch Night services hasn’t changed much except for the specified religious litanies designated by various denominations. Safety concerns have influenced the timing of services; some are as early as noon on New Year’s Eve, while others take place at 9 p.m. or later.

As congregants bow in prayer minutes before midnight, someone sings, “Watchman, watchman, please tell me the hour of the night.”

The minister replies, counting down the time: “It is three minutes to midnight.”

“It is one minute before the new year.”

Then, finally, he calls out, “It is now midnight — freedom has come!”