More than a third of prospective international students applying to study in the US last year were turned away. The F-1 visa refusal rate surged to 36% in 2023 for a total of 253,355 refusals, higher even than in 2022. What’s more, the rate of refusal for student visas was nearly twice that of refusal for other types of visa, according to US government data presented in an article by David J. Bier, associate director of immigration studies at The Cato Institute.

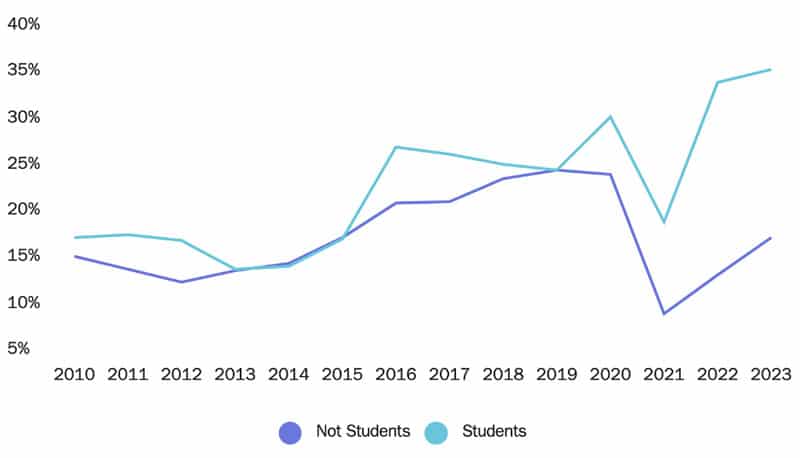

As in Australia, the increasing rate of student visa refusal in the US appears to be exerting downward pressure on applications. Lower application volumes and a declining approval rate have combined to inform a -31% decrease in visa issuances between 2015 and 2023.

Mr Bier has calculated the effect of these trends on the broad US economy:

“It is important to understand that before a student can even apply for an F 1 visa they must already be accepted into a government‐approved university. This means that the US Department of State turned down 253,355 students who would have likely paid roughly $30,000 per year or $7.6 billion per year in tuition and living expenses. Over four years that number rises to $30.4 billion in lost economic benefits to the United States.”

To put that in context, NAFSA last measured the economic impact of international students in the US in November 2023, at which point it explained that, “The over one million international students at US colleges and universities contributed more than US$40 billion to the US economy during the 2022-2023 academic year—up by nearly US$6.3 billion (almost 19%) compared to the prior academic year—and supported more than 368,000 jobs.”

What’s behind the increasing refusal rate?

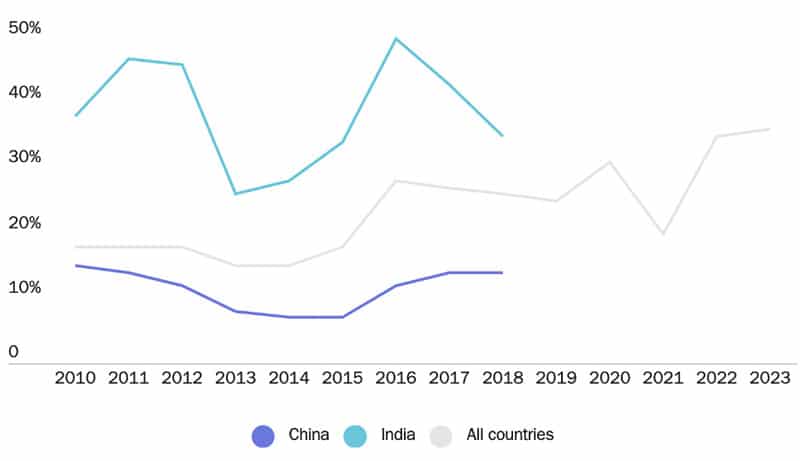

While a number of factors are at play, Mr Bier notes that a particularly influential one may be the rise in Indian applicants. Those applicants received 29% of all visa issuances in 2023 and have historically been more likely than Chinese students to be refused a visa, which means that Indian student applications were likely extremely high in 2023 (though the US government has not released a breakdown of refusals by nationality).

Whatever the data-based reasons for the growing refusal rate, Mr Bier says that it is likely the extreme subjectivity US immigration officials can apply in student visa interviews more than any official immigration strategy that is driving the trend. He provides the example of Don Heflin, the head of the Consular Affairs division of India, who in 2022 explained how his team handled visa interviews:

“Bring [bank statements] just in case the vice consul asks, but we are looking at this less than we used to. We know Indian families usually find a way [to pay].… Mostly it’s about explaining why this school and this curriculum makes sense to you. It’s what in American English we call the Elevator Pitch. You’ll have a minute and a half to tell us why this [school] makes sense to you. Don’t walk up and recite something from memory about the campus, the student body, and how old the school is.… Listen, I have a lot of Indian friends. I know that your father may have told you where you were going to go to school and what you were going to study. That’s fine. Tell us what he told you. Show us that it makes sense for you.”

Mr Bier calls this practice “absurd” and expresses amazement that the US government would willingly pass up billions of dollars in revenue from potential students “just because they memorized their ‘elevator pitch’ on why they want to study computer science in Kansas. It’s totally irrelevant.”

He writes, “The administration needs to increase transparency about student visa denials and adopt a fair and uniform policy for reviews.”

Mr Bier’s sentiments bring to mind those of international education stakeholders in Australia, who are concerned about the subjectivity being applied by their country’s immigration officials when making decisions about which students will be allowed in.

While the US is the outlier of the “Big Four” destinations in not adjusting immigration settings to curb international student numbers this year, its current visa refusal rate nonetheless means that it, like Australia, Canada, and the UK, is becoming less accessible to many international students than in the past.

For additional background, please see:

Source