The Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) has released data showing that in 2022/23, international enrolments in the UK continued to climb to a new peak of 758,855. This represents a 12% increase over the total in 2021/22 (675,200).

It is important to note that the UK is the last of the “Big Four” study abroad destinations to report 2022/23 data, and that the 12% year-over-year growth occurred before the UK government announced that in January 2024, international students (other than those on government scholarships and in research-oriented postgraduate programmes) would lose their right to bring their family with them to the UK.

Preliminary data indicators for 2024 suggest that the next of round full-year HESA reporting on foreign enrolments (2023/24) will show a reversal of the growth trends we are reporting on today.

That said, the 2022/23 data represents an important baseline from which to judge the effect of immigration policy on student mobility to the UK. The last time we had such an opportunity was when the government announced that “Graduate Route” work rights would be restored in 2021. International applications enrolments correspondently surged, with an estimated economic impact in the billions of pounds.

What the 2022/23 data can tell us

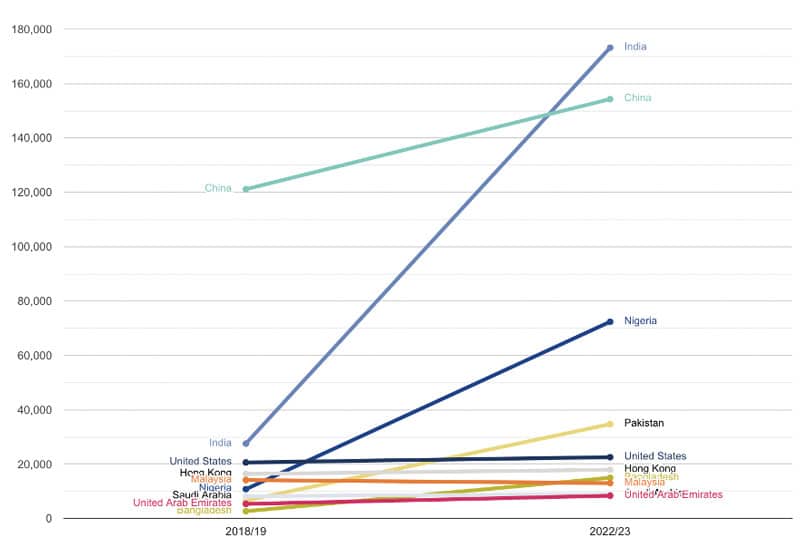

India (173,190 students) surpassed China (154,260) as the main sender of students to UK universities. China had been the #1 market since 2018/19. Indian students represented a quarter (26%) of all international students in the UK in 2022/23.

India (+37%), Nigeria (+39%), and Pakistan (50%) were by far the fastest-growing student source countries, year-over-year.

The top 10 non-EU sending markets were:

- India (173,190, +37%)

- China (154,260, +2%)

- Nigeria (72,355, +39%)

- Pakistan (34,690, +50%)

- US (22,540, -2%)

- Hong Kong (17,095, +3%)

- Bangladesh (14,945, +18%)

- Malaysia (13,005, +7%)

- Saudi Arabia (9,045, +3%)

- UAE (8,350, +3%)

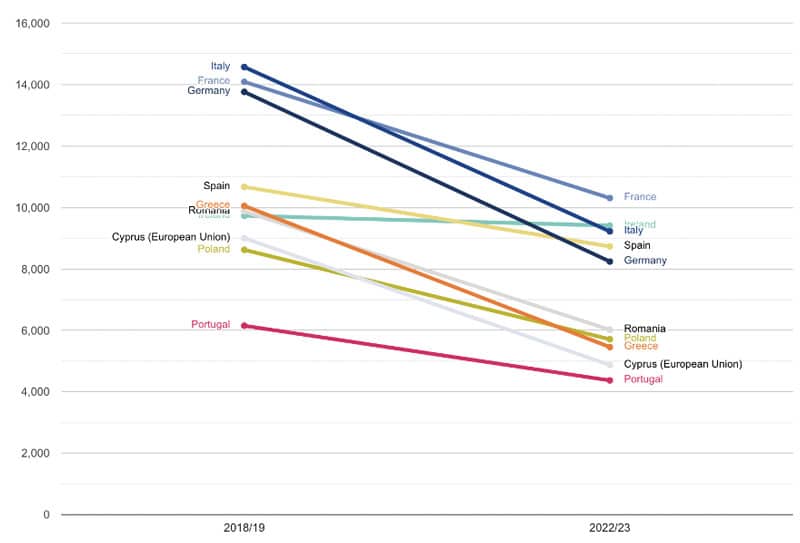

Non-EU enrolments continued to decline (overall, by 8%), as shown in the following chart. Only Ireland sent more students in 2022/23 than in 2021/22 (+5%). The steepest declines were from Poland, Romania, Greece, and Cyprus. Students from Europe have had less incentive to choose the UK over other top destinations since Brexit, when they lost their “home fee” status and became less eligible for financial aid.

The top EU markets were:

- France: 10,305 (-15%)

- Italy: 9,220 (-23%)

- Spain: 8,730 (-18%)

- Germany: 8,240 (-20%)

- Ireland: 9,410 (+5%)

- Romania: 6,020 (-48%)

- Poland: 5,710 (-39%)

- Greece: 5,455 (-30%)

- Cyprus: 4,870 (-30%)

- Portugal: 4,370 (-41%)

Lag in data reporting begs questions

The UK government introduced the so-called “dependants ban” in 2024 – ahead of HESA releasing foreign enrolment data for 2022/23. Louise Nicol, founder of Founder Asia Careers Group posed this question in an 8 August 2024 LinkedIn post:

“How on earth can government set policy towards international students and universities forecast their international student recruitment working with data two years in arrears?”

It is a fair question, and one with some urgency attached to it given that:

- Domestic enrolments in UK universities fell 0.3% between 2021/22 and 2022/23 from 2,182,565 to 2,175,530, according to HESA.

- Brexit has sent EU enrolments into a tailspin. Universities UK International (UUKi) and Studyportals research shows that between 2020 and 2021, there was a 37% decrease in the number of EU undergraduate applications to UK universities and a 47% drop in the number of EU students accepted to UK universities. That decline accelerated according to the 2022/23 HESA data.

- In July, data revealed a -16% decrease in student visa applications from July 2023 to July 2024. Mark Corbett, head of policy and networks at London Higher, said that if the trend holds all year, it could equate to almost a billion pounds in lost revenue in 2025.

Essentially, the government is depressing non-EU enrolments through policy at the same time as EU enrolments are declining and UK university recruiters have lost their pricing advantage in Europe due to Brexit.

International education’s sector peak bodies are sounding the alarm. In July 2024, Jo Grady, UCU’s general secretary, wrote a letter to Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson and Skills Minister Jacqui Smith last week in which she stated:

“Anything short of an emergency rescue package for the sector will be insufficient to stave off catastrophe. This funding package should, though, come with conditions such as ensuring jobs are protected. We think there are three universities we have been able to identify that could be close to financial collapse and would benefit from state intervention and support. If they do not get state support they will struggle still and use cuts to staff as shock absorbers. We see this as a systemic crisis. We don’t think parents and prospective students understand the total mess some of our universities are in.”

Last year, the International Higher Education Commission, supported by Oxford International Education Group, released a report warning the government about the perilous state of UK higher education:

“Without urgent actions to diversify markets and ensure a more balanced distribution of international students across programmes of study, the UK HE sector is potentially in an extremely vulnerable position.”

For additional background, please see:

Source