St. Benedict of Nursia The Benediktbeuern Monastery, located in southern Germany at the foot of the Bavarian Alps, is one of the oldest and most renowned monasteries in the country. It was founded in the years 739–740. Its original name was Buron. For over 1,200 years, the relics of  St. Benedict of Nursia, Founder of Western MonasticismFor three years the saint waged a harsh struggle with temptations and conquered them. People soon began to gather to him, thirsting to live under his guidance. The number of disciples grew so much, that the saint divided them into twelve communities. Each community was comprised of twelve monks and was a separate skete.

St. Benedict of Nursia, Founder of Western MonasticismFor three years the saint waged a harsh struggle with temptations and conquered them. People soon began to gather to him, thirsting to live under his guidance. The number of disciples grew so much, that the saint divided them into twelve communities. Each community was comprised of twelve monks and was a separate skete.

“>St. Benedict (†543 or 547) have been kept here, venerated by both the Orthodox Church (commemorated on March 14/27) and the Catholic Church.

The relics—specifically, the radius bone of St. Benedict’s right arm — were gifted to the monastery by the Frankish king Charlemagne (742–814), who was a patron of the Church, shortly before he was proclaimed emperor in the year 800. Because of this precious relic, the monastic community of Buron gained widespread fame and eventually received a new name: Benediktbeuern.

In 1964, Pope Paul VI proclaimed Benedict of Nursia the heavenly patron of Europe, in recognition of the profound influence he and the Benedictine monks had on the shaping of Christian culture. In the Catholic Church, St. Benedict’s feast day is celebrated on July 11. On this day, pilgrims from all over Germany, as well as from Austria, Switzerland, and northern Italy, gather in Benediktbeuern to honor the saint.

A special reliquary was crafted for St. Benedict’s relics in 1794 by Munich artisan Peter Streizel. The reliquary is uniquely shaped in the form of the saint’s right hand. Through the glass inset in the silver reliquary, one can see the relics wrapped in a ribbon adorned with precious stones.

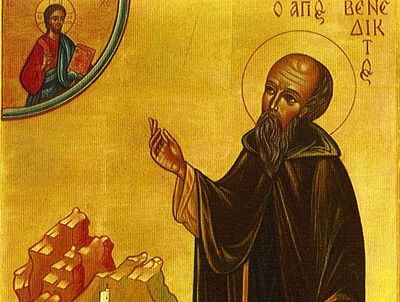

The earliest known depiction of St. Benedict, dating back to the eighth century, shows him in black monastic robes, holding a scroll of his Rule, inspired, like an evangelist, by an angel. Characteristic iconographic symbols of Saint Benedict, particularly in Catholic tradition, include:

-

a book,

-

a staff,

-

a bundle of rods,

-

a raven with a piece of bread in its beak,

-

and a cracked chalice or, alternatively, a chalice with a serpent, referencing the attempted poisoning of the saint, as described in his hagiography.

All these elements can be seen in the wall paintings of the Benediktbeuern Monastery.

The Benediktbeuern Monastery

The Benediktbeuern Monastery

Historical Information and Accounts of the Life of Saint Benedict are preserved in the Dialogues of St. Gregory the Great, Pope of Rome, and in the work, On the Illustrious Men of the Abbey of Monte Cassino by the medieval chronicler Peter the Deacon (twelfth century).

Benedict of Nursia, whose name in Latin means “blessed,” was born around the year 480 near the town of Nursia (modern-day Norcia in the region of Umbria, Italy) into a noble family. He had a twin sister, Scholastica, who, like her brother, devoted her life to strict asceticism.

In his youth, Benedict studied the liberal arts in Rome, but soon abandoned his studies and withdrew to live an ascetic life in the region of Effide (Affile), about sixty kilometers from Rome. Seeking even greater solitude, he left that place and around the year 500 settled in a cave in the region of Subiaco, where he was supported by a monk named Romanus from a nearby monastery, who would occasionally bring him meager food.

After three years, news of Benedict’s ascetic feats spread throughout the surrounding region. Monks from a nearby monastery, likely Vicovaro, invited him to become their abbot. However, after a time, dissatisfied with his strict leadership, the monks attempted to poison him. According to tradition, their evil intention was miraculously thwarted—when Benedict blessed the cup of poisoned wine, it cracked and split.

Upon discovering their plot, Benedict left the monastery and returned to his cave in Subiaco. Soon, disciples and followers began to gather around him. The holy hermit founded twelve small communities, appointing an abbot over each and placing twelve monks in each one. He remained the spiritual guide of them all, keeping a few disciples close to himself.

However, due to the intrigues stirred up by a local priest from a neighboring church, St. Benedict left Subiaco and moved to Campania, where in the year 529, near the site of a former Roman military camp, he founded a cenobitic monastery on a mountain called Monte Cassino and became its abbot.

The structure of monastic life at Monte Cassino was laid out in the rule written by St. Benedict, known as the “Rule of Saint Benedict” (Regula Benedicti). In it, the saint compiled and reflected upon the ascetic experience of both Eastern and Western monastic traditions. As he himself stated, St. Benedict aimed to establish a “school for the service of the Lord.”

In writing his rule, he also drew on the earlier anonymous monastic rule known as the “Rule of the Master” (Regula Magistri).

He found practical examples of monastic life both in Holy Scripture and in the earthly life of Jesus Christ.

The Rule places its primary emphasis on the principles of coenobitic monastic life as the main path to achieving sanctity, and on the virtues of humility and obedience.

The 72 Instruments of Good Works from the Rule of Saint Benedict are widely known:

The 72 Instruments of Good Works from the Rule of Saint Benedict are widely known:

-

To love the Lord God with all one’s heart, soul, and strength.

-

To love one’s neighbor as oneself.

-

Not to kill.

-

Not to commit fornication.

-

Not to steal.

-

Not to covet.

-

Not to bear false witness.

-

To honor all people.

-

To do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

-

To deny oneself.

-

To discipline the body.

-

Not to be attached to sensual pleasures.

-

To love fasting.

-

To relieve the poor.

-

To clothe the naked.

-

To visit the sick.

-

To bury the dead.

-

To help those in tribulation.

-

To comfort the sorrowful.

-

To shun worldly ways.

-

To prefer nothing to the love of Christ.

-

Not to give way to anger.

-

Not to seek revenge.

-

Not to harbor deceit in the heart.

-

Not to give a false peace.

-

Not to forsake mercy.

-

Not to swear, lest one fall into perjury.

-

To speak the truth with heart and lips.

-

Not to return evil for evil.

-

To bear patiently wrongs done to oneself.

-

To love one’s enemies.

-

To bless those who curse you.

-

To endure persecution for righteousness’ sake.

-

Not to be proud.

-

Not to be addicted to wine.

-

Not to be a glutton.

-

Not to be drowsy.

-

Not to be lazy.

-

Not to grumble.

-

Not to speak ill of others.

-

To place one’s hope in God.

-

To attribute to God any good found in oneself.

-

To always accuse oneself of one’s sins.

-

To keep in mind the Day of Judgment.

-

To fear hell.

-

To desire eternal life with all spiritual longing.

-

To keep death daily before one’s eyes.

-

To watch over one’s actions constantly.

-

To be certain that God sees us everywhere.

-

To dash evil thoughts against Christ the moment they arise.

-

And to reveal them to one’s spiritual father.

-

To guard one’s tongue from evil speech.

-

To avoid much speaking.

-

Not to speak idle words.

-

Not to love loud or frequent laughter.

-

To listen gladly to sacred reading.

-

To devote oneself often to prayer.

-

Daily in prayer, with tears, to confess past sins to God and to correct them for the future.

-

Not to fulfill the desires of the flesh.

-

To hate one’s own will.

-

To obey the commands of the abbot in all things, even if—God forbid—he acts otherwise, remembering the Lord’s saying: Whatsoever they bid you observe, that observe and do; but do not after their works (Matt. 23:3).

-

Not to wish to be called holy before one is so.

-

To fulfill daily the commandments of God in one’s deeds.

-

To love purity.

-

To avoid hatred.

-

Not to be jealous or envious.

-

Not to love strife.

-

To flee from vainglory.

-

To honor the aged.

-

To love the young.

-

To pray for one’s enemies in the love of Christ.

-

To make peace with those with whom one has quarreled before the setting of the sun.

-

And never to despair of God’s mercy.

The Rule of Saint Benedict spread throughout monasteries across Western Europe and played a key role in the development of a distinct monastic community—the Catholic Benedictine Order. The original handwritten manuscript of the Rule, penned by St. Benedict himself, was first preserved at Monte Cassino, then in Rome, and later in Teano. However, the original was lost during a fire at the monastery in Teano in 896.

The Rule of Saint Benedict spread throughout monasteries across Western Europe and played a key role in the development of a distinct monastic community—the Catholic Benedictine Order. The original handwritten manuscript of the Rule, penned by St. Benedict himself, was first preserved at Monte Cassino, then in Rome, and later in Teano. However, the original was lost during a fire at the monastery in Teano in 896.

It is known that in 787, by order of the Frankish king Charlemagne, a copy of the Rule was made from the original manuscript. This copy was transferred to Aachen, though it later disappeared without a trace. In 817, monks from the Reichenau Monastery on Lake Constance created another copy, based on the Aachen version commissioned by Charlemagne.

St. Benedict was widely revered even during his lifetime for his piety, ascetic life, selflessness, compassion, and the miracles worked through his prayers. The Lord revealed much to him. On one occasion, while praying at night by a window, the saint suddenly saw a great light descending from heaven, such that the night became brighter than the day. It seemed to him that he could see the entire universe, as if it were gathered together under a single sunbeam.

St. Benedict foresaw the day of his own death. He reposed in the Lord a few days after the death of his sister Scholastica, on March 21, in the year 543 or 547. According to tradition, he was buried in the monastic church he built in honor of St. John the Baptist, in the same tomb as his sister.

The relics of St. Benedict remained at Monte Cassino until 672, when the monastery was ravaged by the Lombards. The monks rescued the relics and brought them to the Frankish Kingdom, to the monastery of Fleury (then called Floriacum; now Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire) in Gaul.

Later, Charlemagne received a portion of the relics from the Gallic monks and presented them as a gift to the monastery of Buron (now Benediktbeuern). Another portion was returned by the monks between 755–757 to the rebuilt Monte Cassino. The relics that remained in Fleury were preserved during a Norman invasion, and in 883, they were transferred to a new church, where they remained until 1562, when they were miraculously saved from destruction by the Huguenots who plundered Fleury. In 1663, the relics were placed in a specially constructed mausoleum.

According to the monks of Benediktbeuern, the tomb of St. Benedict at Monte Cassino was completely destroyed during World War II, but his relics kept in the monastery church survived. After the war, the monastery was restored by the Italian government and reconsecrated in 1964.

Veneration of St. Benedict as a lawgiver and reformer of Western monasticism is especially widespread in Bavaria. Among the pilgrims visiting his relics in Benediktbeuern, there exists a tradition of taking home a copy of the “Benediktenpfennig.”

The Benediktenpfennig is a commemorative medal-coin first minted by the Benediktbeuern Monastery in the seventeenth century specifically for pilgrims. It bears a raised image of St. Benedict, surrounded by a Latin inscription in the form of a circular legend. This inscription contained an abbreviated form of a protective blessing attributed to St. Benedict, which warns against temptation and sin. The letters: V. R. S. N. S. M. V. – S. M. Q. L. I. V. B. stand for the Latin phrase: “Vade Retro Satana, Nunquam Suade Mihi Vana. Sunt Mala Quae Libas. Ipse Venena Bibas,” which means, “Begone, Satan, and do not tempt me with your vanities. The cup you offer is evil—drink your own poison.”

These coins became highly popular among the faithful in Bavaria, Austria, and Switzerland.

Pilgrims to Benediktbeuern often also visit another Bavarian city—Kempten, which holds an indirect connection to Monte Cassino: a fragment of an ornamented pilaster from the Italian monastery of St. Benedict has long been preserved there.

Source: Orthodox Christianity