Increasingly we live in a digital world: e-cards, Google calendars, the Contacts phone app.

“The Notebook” (Profile Books, $31), by Roland Allen, subtitled “A History of Thinking on Paper” celebrates the age-old practice of writing things down — numbers, images, thoughts, dreams — and charts the evolution of this handy, humble little item that many of us consider indispensable but to which I, for one, had never given much thought.

Allen begins by recounting the surprisingly absorbing history of the Moleskine, forever romantically associated with Hemingway, Matisse, and the nomadic English travel writer Bruce (“The Songlines”) Chatwin.

Maria Sebregondi, the creator of the modern classic Moleskine, suggests that the notebook’s minimal form — black clothbound covers, thread binding, elastic closure, an internal bellowed pocket for maps, dried flowers, insect specimens — makes it the perfect creative tool: a “simple object” generating a “sense of extraordinary possibility born of small things.”

The notebook’s “practical effectiveness” has been noted by many. Far more interesting, to my mind, is Allen’s conviction that the very incarnate, kinesthetic act of writing something down has a kind of larger, (he doesn’t use the word, but I will) spiritual value.

“The laptop, the BlackBerry, the iPhone, and the iPad all seemed to offer greater functionality than their paper antecedent,” he writes, “but a stubborn constituency of users refused to move over into the digital sphere, and numerous peer-reviewed studies soon showed that their obduracy made sense. Something about the act of writing by hand, and the production of a physical object, makes the older technology more effective than the new. Sebregondi had, unwittingly, prompted serious inquiry into the workings of the human brain.”

From the contemporary Moleskine, Allen goes back to the beginning: cuneiform on clay tablets, long scrolls of papyrus. Then things jumped ahead: a small hinged writing tablet of wood and ivory, palm-sized when folded, that was found in the Ulu Burum shipwreck off Turkey’s southern coast. Recesses were cut into the two leaves, filled with wax (that could be smoothed over and used again), and written on with a stylus.

The ship went down in 1305 B.C. and archaeologists estimate that similar tablets constituted Europe’s “notebooks” for 2,000 years.

The Romans adapted the Ulu Burun-style tablets, made them more capacious, and called them pugillares (“hand-helds”) or tabellae.

Then they started using parchment, adapted from the Greeks and again, improved: the Codex Sinaiticus, its 694 pages made of calf- and sheep-skin parchment, was the pinnacle of fourth-century bookbinding.

Meanwhile, a Han dynasty eunuch had discovered how to make paper from pulp vegetable fibers.

While the codex spread across the Roman Mediterranean and Near East, paper eventually moved west from China to the Islamic world. East and West met in Spain in the early 1200s when paper ledgers appeared, accounting was invented and, in Allen’s telling, the entire world was pretty much transformed.

“Business as we know it dates from this era,” Allen observes, quoting historian Jacob Soll: “Without double-entry accounting, neither modern capitalism nor the modern state could exist.”

Italy — with its love for handmade goods and fine craftsmanship that continues to this day — pushed the progression yet further. In the mid-13th century, the papermakers of Fabriano, a town 200 km east of Florence, developed the watermark, the water-powered multiple hammer mill, and a finish that consisted of coating vegetable fibers with gelatin from stewed animal bones.

The resulting sheets were easier to write on with a scratchy nib and the Fabrianese dominated paper production in Italy for 50 years. New trades sprang up: cartolai (stationery shops) and librai (bookshops).

Wandering around the Tuscan countryside, Allen asserts, the early Renaissance painter Cimabue developed the sketchbook. Giotto, his contemporary, followed suit. From 1300 to 1500, medieval artists in Florence and beyond could draw life from everyday people and objects with a new immediacy and freshness; were also able to plan, revise, and prepare before executing the final subject on canvas.

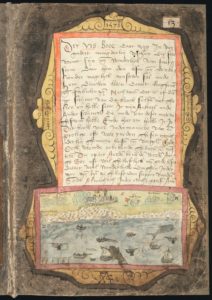

A page from Adriaen Coenen’s “Fish Book,” 1577. (Library of Congress)

As Leonardo da Vinci observed: “And take a note … with slight strokes in a little book that you should always carry with you … preserved with great care; for the forms, and positions of objects are so infinite that the memory is incapable of retaining them, wherefore keep these sketches are your guides and masters.”

Humans being what we are, it wasn’t long before we figured out other uses for the notebook; namely, writing down our own daily activities, thoughts, desires, plans, complaints, and obsessions.

From 1300 to 1500, notebooks were increasingly used in the home: not just for personal accounts, but for recording gambling winnings and losses, the births and deaths of children, family histories, conversations, poems, prayers, songs, recipes, and puzzles.

On it goes: Venetian scholar Antonio Pigafetta’s illustrated chronicle of Magellan’s expedition to the Spice Islands; a celebrated 410-page “fish book” (1580) by Adriaen Coenen (available digitally at the Library of Congress); tattered notebooks of song passed hand to hand for centuries in Franciscan monasteries; more recently, informal “patient diaries,” kept as a labor of love by Danish ICU nurses for those who are unconscious or unaware in order to “recover lost time” when and if the patient heals.

I like to save my old notebooks and stack them on my bookshelves: mementoes of trips I’ve taken, books I’ve read, to-do lists I’ve long ago checked off. Now I know I’m in good company. The more things change, as the French say, the more they remain the same.