Everyone striving for Christ, in addition to the labor dedicated to church service, inevitably faces the necessity of undertaking a special, inner spiritual struggle. More often than not, it is this invisible, internal effort that ultimately leads a person to the Kingdom of Heaven. In all other respects, we, as unworthy servants, merely do what is required of us. For  St. Nektarios of Aegina

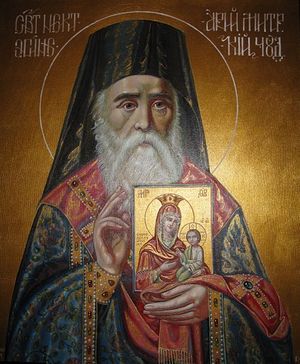

St. Nektarios of Aegina

“>Saint Nektarios (Kefalas) of Aegina, Metropolitan of Pentapolis, this struggle lay in his courageous and humble endurance of envy and slander.

A letter from God

Anastasios Kefalas was born into a large family in Silivria in 1846. His parents, especially his mother, provided him with a strong Christian upbringing. From an early age, the young Christian displayed a thirst for knowledge and a desire to serve Christ. At the age of fourteen, he set out for Constantinople, miraculously securing passage on a ship to reach his destination.

Anastasios Kefalas was born into a large family in Silivria in 1846. His parents, especially his mother, provided him with a strong Christian upbringing. From an early age, the young Christian displayed a thirst for knowledge and a desire to serve Christ. At the age of fourteen, he set out for Constantinople, miraculously securing passage on a ship to reach his destination.

However, poverty prevented the curious and gifted boy from immediately pursuing his studies. Anastasios began working in a tobacco factory while educating himself. “He lived in such deprivation that, at one point, in utter need, he decided to write a letter to the Lord, explaining his problems and needs—such was his childlike simplicity and sincerity. ‘I will ask Him,’ Anastasios thought, ‘for an apron, clothes, and shoes, because I have nothing and I am cold…’ Armed with pencil and paper, he wrote: ‘My Christ, I have no apron, no shoes. I beg You to send them to me. You know how much I love You.’ He folded the letter, sealed it, and addressed it: ‘To the Lord Jesus Christ in Heaven.’ Then, with that, he went to the post office.

“On the way, he encountered a neighbor who was a merchant. This meeting, like everything in our lives, was undoubtedly the work of divine providence.

“‘Anastasios, where are you going?’ asked the neighbor. The unexpected question embarrassed the boy, who muttered something in reply while still holding the letter in his hand. ‘Give me your letter; I’ll send it for you.’ Without hesitation, Anastasios handed it over. The merchant took the letter, put it in his pocket, and walked on. Anastasios, joyful, returned home.

“The merchant, approaching the mailbox, noticed the unusual address. Unable to contain his curiosity, he opened the letter and read it. Deeply moved and troubled, he thought to himself that Anastasios was an exceptional child. Undoubtedly inspired by Him who said, Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me (Matt. 25:40), the merchant decided to respond to the letter.

“He wrote a few touching words, enclosed some money in the envelope, and sent it to Anastasios. The Lord’s ‘reply’ came so swiftly that the young saint appeared at work the very next day, dressed in new clothes. Seeing him so well-dressed, his employer was enraged, accused Anastasios of stealing, and mercilessly beat him. The boy protested, crying out that he was innocent and explaining the incredible truth that God had sent him the money.

“‘I have never stolen anything in my life!’ However, the blows continued with such force that the neighbor—the merchant—arrived, drawn by the commotion. He intervened, explaining everything to the cruel employer and saving Anastasios from further inhumane treatment. Thus, through much hardship, the young saint earned his bread, provided for his studies, and even helped his family.”

Wisdom on Tobacco Paper

At the time, Anastasios led a simple life: work, church, prayer, and the reading of edifying writings and Holy Scripture. He transcribed thoughts he found most inspiring into a special notebook made from tobacco paper, later a book entitled, A Treasury of Sacred Thought.

Reflecting on this, he later wrote, “True labor is the result of long and persistent effort, born of a deep desire to spread knowledge with spiritual benefit… Lacking funds, I could not publish my writings. However, I found a way to overcome this obstacle by using cigarette papers from tobacco merchants in Constantinople as pamphlets. The idea seemed fitting, and I immediately set about implementing it. Daily, I transcribed many of my collected thoughts onto these papers. Thus, curious buyers could read them and learn from their wisdom and spiritual value…”

The teacher (didaskalos) within him, as we see, awakened early and remained his lifelong vocation.

A Laboratory under the shadow of the Holy Sepulchre

Holy Hierarch Nektarios of Aegina Anastasios eventually resumed formal education by working as a laboratory assistant in one of Constantinople’s colleges, overseen by the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. There, he was permitted to teach younger students while continuing his studies in the senior classes.

Holy Hierarch Nektarios of Aegina Anastasios eventually resumed formal education by working as a laboratory assistant in one of Constantinople’s colleges, overseen by the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. There, he was permitted to teach younger students while continuing his studies in the senior classes.

At twenty-two, having completed secondary education, he moved to the island of Chios. Working as a teacher, he lived ascetically, spending most of his free time in prayer and contemplation, eating only once a day. Teaching was a ministry to God, not merely a means of improving his financial situation. He taught not only children but also adults, instructing them in piety through both word and example, assisting the needy, and writing extensively.

“During this period of his life, one particularly noteworthy incident occurred. A boy who assisted Anastasios with errands and cooking once, in a moment of carelessness, left a pot on the stove, causing its contents to burn. In anger, Anastasios struck him twice on the back of the head as punishment. However, he immediately repented, asking God for forgiveness. As a penance, he prayed to lose his sense of taste. God granted his request, accepted his repentance, and from that day onward, St. Nektarios never again distinguished the taste of the food he consumed.”

At the time, a light cuff to a child’s head was considered a normal form of discipline—juvenile justice systems as we know them today did not exist. Parents would likely have thanked the teacher for instilling discipline in their child, and not raised objections. Yet Anastasios was deeply troubled, his sense of sin and fear of God preventing him from simply moving on.

Dreams of Mount Athos

In 1876, inspired by conversations with the abbot of the Nea Moni Monastery on Chios, Anastasios took monastic vows with the name Lazarus. Two months later, the Bishop of Chios ordained him a deacon and named him Nektarios.

At that time, the young hierodeacon dreamed of becoming a hermit on Mount Athos. However, he would only visit the Holy Mountain years later, and only briefly, as a pilgrim. The monastery on Chios laid a strong foundation for his monastic life: service to Christ out of deep filial love, obedience to the abbot, and a habit of long and fervent vigils.

People who receive such preparation often live a dual life. On the one hand, they experience inexpressible consolation from the Lord; on the other, equally inexpressible suffering from the attacks of the devil. A turning point in this direction came when one of the benefactors of Chios introduced the knowledge-thirsty hierodeacon to Patriarch Sophronios of Alexandria. Fr. Nektarios made a favorable impression on the patriarch, who advised the young monk to continue his education in Athens. The aforementioned benefactor did everything possible to support this endeavor.

Higher Rank, Greater Humility

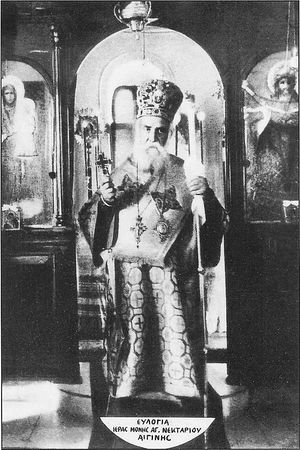

Holy Hierarch Nektarios of Aegina After completing studies at the University of Athens Theological Faculty in 1885, Fr. Nektarios went to Alexandria. There, he ministered to the faithful, undertook inspiring work, experienced a meteoric rise (ordination as a priest in 1886 and as a bishop in 1889), and endured slander, exile, and lifelong estrangement.

Holy Hierarch Nektarios of Aegina After completing studies at the University of Athens Theological Faculty in 1885, Fr. Nektarios went to Alexandria. There, he ministered to the faithful, undertook inspiring work, experienced a meteoric rise (ordination as a priest in 1886 and as a bishop in 1889), and endured slander, exile, and lifelong estrangement.

Upon his episcopal ordination, he prayed: “Lord, why have You raised me to such a high rank? I asked You only to make me a theologian, not a metropolitan. From my youth, I begged You to allow me to be a humble laborer in the field of Your divine Word. Yet now You test me in such matters. Lord, I submit to Your will and pray: cultivate in me humility and other virtues as only You know. Grant that I may live my earthly life in accordance with the words of the blessed Apostle Paul: I am crucified with Christ: nevertheless I live; yet not I, but Christ liveth in me (Galatians 2:20).”

And Here Is What He Wrote to a Monk in Response to a Letter of Congratulations: “Your humility inspires in you a sense of inequality between yourself and me because of my episcopal rank. This rank is indeed great, but only in itself and for itself. It elevates the one who bears it because of its objective value, but it does not in any way change the relationship between the one vested in this dignity and his brothers in Christ. These relationships always remain the same. That is why there is no inequality between us. Moreover, the one who bears the episcopal rank must serve as an example of humility. If a bishop is called to be first, it is in humility, and if he is first among the humble, then he must therefore be the last of all. And if he is the last of all, in what does his superiority consist?…

“Among brothers in Christ, regardless of rank, those who imitate Christ are distinguished, for they bear within themselves the image of the Archetype and the grace of the Holy Spirit, which adorns and exalts them to the heights of glory and honor. Only this honor introduces distinctions and inequalities…

“I assure you that every day I envy those who have devoted themselves entirely to God, who live, move, and have their being in Him. What could be more honorable and radiant than such a life? It skillfully works to restore the image to its original beauty. It leads to bliss. It sanctifies the one who possesses it. It adorns the one who lives by it. It instructs in truth. It makes the Divine Word resonate in the heart. It confidently leads a person to heaven. It turns breath into an unceasing melody. It unites man with angels. It makes man like unto God. It raises us to the Divine and brings Him close.

“This, my beloved brother, is my conviction, which compels me to regard an ascetic as greater than a bishop, and I confess this with all humility.”

Several key points stand out in St. Nektarios’ words. First, he continued to strive for a life of asceticism. Second, he sincerely equated himself with a simple monk, refusing to identify himself with his rank. Third, his words are filled with spiritual poetry, testifying to his deep love for God. Most importantly, he possessed genuine confidence that the chief virtue of a bishop must be supreme humility, thereby imitating Christ.

It can be presumed that, to a certain extent, the Lord revealed to St. Nektarios the greatness of this gift. That is, he experienced the true grace of humility—not merely in words, as we often do, but in reality, through the Holy Spirit. His subsequent life provided him with the opportunity to affirm this virtue.

Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you

The devil continually stirred up slanders against St. Nektarios until the last days of his life, each accusation more monstrous than the last. The most painful aspect of these attacks was that they were often fabricated, yet believed by his fellow clergy or by those whom he had helped.

The devil continually stirred up slanders against St. Nektarios until the last days of his life, each accusation more monstrous than the last. The most painful aspect of these attacks was that they were often fabricated, yet believed by his fellow clergy or by those whom he had helped.

As a result, the “traveling bishop” (as St. Nektarios began to call himself) faced humiliation, poverty, and the many “joys” of an unjustly slandered life.

Though the Lord dealt with his slanderers, this offered no comfort to St. Nektarios. He would have preferred they remain silent, refraining from poisoning his life, and die righteous deaths. Yet, he understood that all these machinations were the devil’s tests of his faithfulness to Christ, and forging his virtues. Therefore, we will not give undue attention to the devil by detailing his deeds but will instead focus on the labors of Bishop Nektarios.

After the first wave of slander, he was expelled from Alexandria with a “wolf ticket”—a vague letter of recommendation so ambiguous that the saint initially could not find a place to settle in Greece. As soon as he secured a position, the Alexandrian slander followed him.

Once again, the saint was plunged into poverty. However, a kind-hearted landlady in Athens, recognizing his ascetic life, offered him lodging and food free of charge. The Lord also raised up good people who refuted the malicious accusations of his detractors.

After a period of deprivation, the Metropolitan of Pentapolis became a traveling preacher in Euboea and Phthiotis, tirelessly sowing the Word of God in those regions. His sermons immediately drew attention because he was both deeply learned—a rare trait among Greek preachers of the time—and exceedingly humble, following Christ with childlike simplicity. People believed St. Nektarios because hespoke from his genuine experience of life in God.

The devil’s schemes continued, not only through attacks by people but also through direct demonic assaults. The saint responded with humility and prayer.

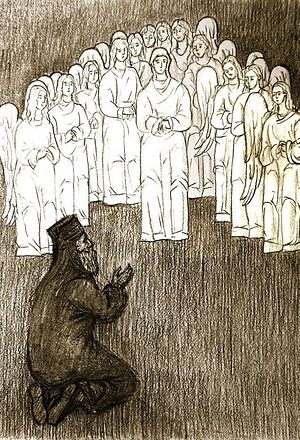

“One day, when St. Nektarios, exhausted by poverty and shaken by the betrayal and distrust of his friends and loved ones, was praying in brokenness of heart, an extraordinary peace descended upon him. It seemed to him that he could hear harmonious singing. Realizing what was happening, he raised his eyes and saw the Most Holy Theotokos accompanied by a host of angels, singing a unique melody. He wrote down the words and the melody (later adding additional verses). This beautiful hymn to the Theotokos, known as ‘Agni Parthene’ (‘O Pure and Ever Virgin’), is now beloved throughout the Orthodox world.”

Sweep, Nektarios!

In 1894, the disgraced hierarch St. Nektarios found relative stability when he was appointed director of the Rizarios School, primarily a seminary for preparing clergymen. He was also allowed to serve in the school chapel, something previously forbidden to him.

In 1894, the disgraced hierarch St. Nektarios found relative stability when he was appointed director of the Rizarios School, primarily a seminary for preparing clergymen. He was also allowed to serve in the school chapel, something previously forbidden to him.

St. Nektarios was an unusual director. His work can be aptly described by the late M. E. Kirillova’s words: “He was not only a clergyman but also a Christian,” which, alas, could not be said of many opponents of the Metropolitan of Pentapolis.

“When a report came to the director about a student’s bad behavior, he would summon the student and accept his explanations, trusting the accused more than the accusers. One student recalled that, instead of punishing those who violated school discipline, St. Nektarios would punish himself by fasting. This same student saw him three times impose such fasting on himself for disturbances caused by student misconduct.

“St. Nektarios was a loving father, not only to the students but also to the school staff.

“One nun from Aegina, who knew the saint from his time as the school director, shared this story. The school’s caretaker, who was responsible for cleaning and maintenance, fell seriously ill and was sent to the hospital. In those days, Greece lacked social insurance, and the poor man feared losing his job if he was replaced.

“When he recovered, he returned to the school and found it in perfect order and cleanliness. Returning home, he told his wife that someone else must have been hired to replace him. She encouraged him to visit the school early in the morning to speak with his replacement. Arriving at 5 a.m., the caretaker met his ‘replacement’—St. Nektarios himself, sweeping the latrines and murmuring to himself: ‘Sweep, Nektarios; this is all you are worthy of doing.’

“Seeing his staff member, the saint called him over and said: ‘Come here and don’t be surprised. Just listen to me carefully. You are shocked to see me cleaning the school, but don’t be afraid—I’m not taking your job. On the contrary, I’m doing everything I can to keep it for you until you fully recover. You’ve just left the hospital and can’t work for at least two more months. What will you do if you’re dismissed? How will you live? That’s why I’ve stepped in to help. But be careful: while I am alive, no one must know what you’ve seen.’”

Another time, a visitor approached the saint and was greeted as an old friend. “Holy Father,” the man said, “I owe twenty-five drachmas, and I must repay them tomorrow, but I have no money. I don’t know what to do. Please, help me.”

St. Nektarios called for Kosti, the treasurer. Kosti, overhearing the conversation, pretended not to hear. There were barely thirty drachmas left in the treasury, and the month was just beginning. St. Nektarios summoned him again. This time Kosti responded.

“Give this man twenty-five drachmas,” said the saint. “He desperately needs them.”

“There’s nothing left, Holy Father,” replied Kosti.

“Search again, Kosti. He truly needs them.”

“We have only twenty-five drachmas in the treasury, and it’s the start of the month.”

“Give them to him, Kosti. God is great!”

Kosti handed over the money, and the visitor left. That same day, St. Nektarios received a note from the archbishopric asking him to substitute for a sick archbishop at a wedding. After the ceremony, St. Nektarios was given an envelope containing one hundred drachmas. He handed it to Kosti, saying: “We have nothing, but God possesses everything, and He cares for us.”

The Bishop-Laborer

Many people came to Met. Nektarios’s services and for confession. Among his penitents were a few devout young women, one of whom was blind. They asked him to guide them on their path to monasticism. Thus was born the famous  How to Find Yourself in a Transfigured WorldInstead of an answer, St. Nektarios prayed, and the nuns found themselves in a transfigured world, where they heard how every tree, every flower, and every little blade of grass sings the glory of the Lord.

How to Find Yourself in a Transfigured WorldInstead of an answer, St. Nektarios prayed, and the nuns found themselves in a transfigured world, where they heard how every tree, every flower, and every little blade of grass sings the glory of the Lord.

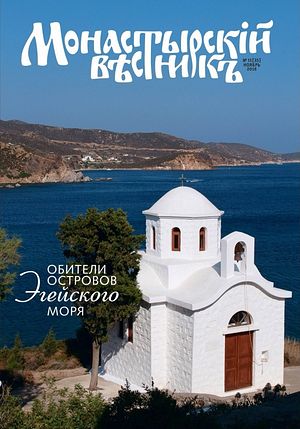

“>Holy Trinity Convent on the island of Aegina, where St. Nektarios spent the last twelve years of his life.

He helped the sisters acquire the ruins of a monastery on Aegina, and they began restoring it. St. Nektarios oversaw the construction of the convent, often working alongside the builders between 1906 and 1908. At the age of 62, he requested to retire as school director and moved permanently to Aegina.

The locals already knew him as a man of prayer and a miracle worker. Stories of his exorcisms and prayers for rain during a three-year drought were well known.

At the convent, the bishop continued to preach and work as a simple laborer. However, the devil unleashed another wave of slander against him and the convent. Though the accusations were quickly disproven, the stigma followed him even after death.

An ascetic who lived on Aegina recounted that St. Nektarios was seen praying in the church before the holy icons, tears streaming from his eyes, for three days and nights without food or water. No one knows the trial he endured during that time. Only after an appearance of the Angel of the Lord did he leave the church, having overcome the temptation, and return to his usual daily life.

In his final months, St. Nektarios endured severe pain from cancer. Shortly before his death, he was admitted to a poor person’s ward in an Athens hospital. The attending physician was astonished by the saint’s humble, monastic appearance:

“This is the first time I’ve seen a bishop without a pectoral cross, gold, or money.”

St. Nektarios reposed on November 8/22, 1920. Miracles began immediately after his death. While preparing his body for burial, his shirt accidentally touched the bed of a paralyzed man, who was instantly healed. The saint’s body exuded myrrh, and the heavenly fragrance lingered in the hospital for days.

Three years after his burial, St. Nektarios’ incorrupt and fragrant relics were discovered. On April 20, 1961, he was canonized as a saint by the Universal Church.

Risen in the Flesh

During World War II, when the Nazis attempted to bomb the island of Aegina, their efforts were thwarted by the prayers of St. Nektarios. Despite clear sunny weather, they could not locate the island amidst the sea, while other islands were perfectly visible.

One of St. Nektarios’ more recent miracles cannot be left untold.

A few years ago, a mountain village on Aegina was left without a priest. As time passed, and no replacement was assigned, the villagers grew anxious. When Great Lent approached, they became deeply concerned—remaining without a priest during this holy season was unthinkable. After consultation, they decided to write to the diocesan bishop:

“Holy Master,” they pleaded, “please send us a priest, at least for Holy Week and Pascha. We wish to prepare ourselves worthily, repent, pray, and joyfully celebrate the Bright Resurrection of Christ with peace.”

The bishop read their letter and presented their request during the next diocesan council. “Who among you, Fathers, can go to this village?” he asked. However, each priest gave reasons for being unable to go. The council moved on to other matters, and the villagers’ letter was buried under a pile of papers, eventually forgotten amidst the preparations for Pascha.

The Great Day of Christ’s Resurrection arrived, celebrated across Greece with unparalleled joy and splendor. After Bright Week, the diocesan staff returned to their offices, and soon the bishop found another letter from the mountain village on his desk.

“Holy Master!” the villagers wrote, “There are no words to express our gratitude and heartfelt appreciation for your pastoral care and help to our parish. We will forever thank God and you, Holy Master, for the devout priest you sent us to celebrate Pascha. Never have we prayed with such a gracious and humble servant of God…”

The bishop opened the next diocesan council with the question: “Which of you went to the village mentioned in the letter?” Silence filled the room—no one responded. The bishop was bewildered and deeply curious.

A few days later, the bishop and his entourage set out on the rocky roads of Aegina, raising dust on their way to the mysterious village. For the first time in history, the bishop visited this forgotten place, accompanied by a splendid procession. The villagers greeted them in full assembly—from the eldest to the youngest—with Paschal bread, cookies, dyed eggs, and flowers, leading them to their small, ancient church.

In Greece, all priests are considered government officials, and even if they serve in a church only once, they are required to record their service in a special church journal. After venerating the church’s cherished icon, the bishop went straight to the altar. Through the open Royal Doors, everyone could see him take the journal and move to a tall, narrow window. Flipping through its pages, he ran his finger along the last entry, written in elegant script: “Nektarios, Metropolitan of Pentapolis.”

The bishop dropped the journal and fell to his knees.

News of this great miracle spread like thunder through the congregation. A stunned silence gave way to an outpouring of emotion. People knelt, raised their hands to heaven, embraced one another, wept, and loudly thanked God and St. Nektarios.

For an entire week, St. Nektarios—who had passed away in 1920—was present in the flesh with the humble shepherds and their families. He served in their church, led them in processions, presided over solemn nighttime epitaphios processions with the Holy Sepulchre, sang hymns and prayers with them, comforted them, and taught them. His words about God were unlike anything they had ever heard. It seemed as if this grace-filled elder with a gentle voice knew God personally.

Only later did the villagers realize why an otherworldly joy had filled their hearts during that time, why tears of repentance and tenderness flowed freely, with no one trying to suppress or hide them. Why they had no desire to eat or sleep, but only to pray with this extraordinary, kind priest.