At the same time as leading Western destinations – e.g., Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom – are applying brakes to slow or reverse the expansion of their foreign enrolment, several Asian destinations are doing the opposite: pursuing policies to boost international enrolments to record-high levels.

Japan, Malaysia, Taiwan, and South Korea have all set ambitious new international enrolment targets. These are:

- Japan: 400,000 by 2033

- Malaysia: 250,000 by 2025

- Taiwan: 320,000 by 2030

- South Korea: 300,000 by 2027

To date, this is the progress the four destinations have made:

- Japan: 279,275 international enrolments as of May 2023 (+21% over 2022).

- Malaysia: Between 115,000 and 170,000 enrolments currently (estimates vary). Malaysia tends to report application volumes publicly rather than enrolment volumes. Looking at this measure, Malaysian institutions received 58,285 applications in 2023, a 14% increase over 2022 following a 28% increase the previous year. Asia contributed the most growth – especially East Asia (+22% over 2022).

- Taiwan: 116,040 in 2023, representing a 90% recovery from foreign enrolment losses in the pandemic. Just over 6 in 10 (61%) of Taiwan’s international students are from “New Southbound Policy” (NSP) countries: Brunei Darussalam, Burma, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, Australia, and New Zealand.

- South Korea: 205,170 as of March 2023 (+23% over 2022).

South Korea is thus approaching the volume of Japan’s current foreign enrolment as it adheres to a strategy known as the Study Korea 300K Project. That strategy aims to position South Korea as one of the world’s top 10 study abroad destinations by 2027.

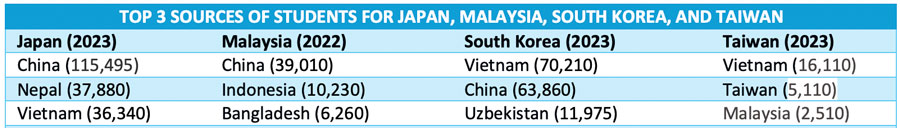

The following table shows top markets for each of the four Asian destinations. It also demonstrates the large number of Vietnamese students opting to study in Asia as opposed to the West. For example, South Korea enrols more Vietnamese students than do Canada (17,175) and the US (21,900) combined.

How is South Korea working towards its goal?

Here are some of the tactics and policies at the heart of the Study Korea 300K Project:

- In 2023, the part-time work allowance for international students enrolled in language studies or bachelor’s programmes increased from 20 hours per week to 25 hours per week. Master’s and doctoral students can work 35 hours during the weekdays. All international students are permitted to work unlimited hours on weekends/holidays.

- Also in 2023, the financial requirement for international students to get a D-2 visa (for degree studies) was lowered from to 20 million won (just under US$15,400). Previously, the financial threshold had been US$20,000. In addition, degree-seeking international students applying to universities outside of the Seoul metropolitan area is lower still: 16 million won.

- In 2025, the South Korean government will allow international students to remain in the country for up to 3 years to look for a job; currently the allowance is 6 months with a possible extension to a maximum of 2 years.

- Also planned for next year: expanding the type of jobs for which international students can apply and extending the amount of time job holders can remain in the country. Currently, foreign graduates are eligible only for a limited number of visas that lead to specialist jobs.

- The government’s Global Korea Scholarship (GKS) programme is being expanded to double the number of scholarships available for STEM students (to 2,700). There are now also 6,000 scholarships for international students pursuing non-STEM degrees, up from about 4,500 last year.

- STEM graduates are to be fast-tracked for permanent residency, and graduate and postgraduate students graduating from Korean universities will see the residency requirement for their permanent residency application reduced from 6 to 3 years.

- Korean universities now accept a wider band of tests to prove Korean-language proficiency, and there is also a controversial proposal to lower the level required on the Test of Proficiency in Korean (TOPIK) for international students. (Some academics are worried that this may reduce international students’ ability to succeed in their Korean-taught programmes.)

Too much ambition?

Some media outlets have reported on Korean academics’ concerns that the means being used to advance the Study Korea 300K Project – such as easing language requirements and pursuing a high rate of annual international enrolment growth – may put too much pressure on universities to support students well enough.

Song Ki-chang, emeritus professor of education administration at Sookmyung Women’s University, told University World News last year that attracting international students by easing entrance conditions “can be effective to secure new student numbers but if their language proficiency is not enough the education cost for quality education may work as another financial burden (on universities).”

And earlier this year, upon news that the threshold for Korean universities to obtain certification in the International Education Quality Assurance System would be lowered, Jun Hyun Hong, professor of public policy at Chung-Ang University, said: “I am concerned that pursuing a goal too aggressively may lead to the indiscriminate [recruitment] of international students, which has the potential to lower the quality of international students.”

However, the South Korean government is working to maintain quality standards. Following an annual evaluation of colleges and universities’ capacity and performance with respect to international students, it announced in February 2024 that it had stripped the right of 20 degree programmes and 20 language-training programmes to issue visas to international students for one year from the second semester of 2024. At the same time, it certified 14 more degree-granting institutions (to 134) for and 15 more language programmes (to 90) compared with 2023 based on the results of the evaluation.

Increasing supports for international students will be key

South Korea has historically had a reputation for being a tough market for international graduates to find a job in after their studies are completed. International students have had to jump through hoops to move from one visa category to the next to be able to remain in the country, all the while searching in what seems like a small proportion of jobs that international students can be hired for. The Korea JoongAng Daily reported in March 2024 that “…of 7,321 [international] students who graduated from universities or vocational colleges last year, only 8.2 percent got jobs in Korea, according to the Korea Educational Development Institute.”

Kumar Suraj, a 29-year-old Indian graduate student at Hanyang University’s Division of International Studies, was quoted in the Asia News Network last year, saying there is a “gap between education and employment”:

“Many foreign students find it hard to keep track of job openings that accept foreign applicants. They can look for employment opportunities through portal sites, but most recruitment posts are focused on hiring Koreans.”

University World News reported in 2023 that “currently, the rate of settlement for foreign graduates of Korean universities is low compared to some other countries, with studies pointing to a lack of incentives to stay.”

The country is generally facing a serious issue of youth unemployment. Government data released in July 2024 indicate that “the number of South Koreans without a job or seeking a job marked an all-time high in the first half of this year.”

The South Korean government knows very well that the country is competing with other ambitious Asian destinations that are working hard at increasing their retention of international students. For example:

- Japan has a target of enrolling 60% of international student graduates by 2033. This year, the Japanese government announced that foreign graduates of vocational schools and colleges – not just universities – can now look for a job after completing their studies without having to find work in a job/industry related to their field of study.

- Hong Kong extended students’ post-graduation stay allowance to 2 years in 2022, and Taiwan followed suit in 2024.

- Malaysia has also had a reputation for being a difficult job market to crack for international students. This year, it introduced the “Social Visit Pass” which allows graduates of Malaysian degree programmes from a list of eligible countries to remain in Malaysia for up to a year to look for employment. Eligible countries are Australia, New Zealand, Brunei, Singapore, South Korea, Japan, Germany, United Kingdom, France, Canada, Switzerland, Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, United States, Oman, and Bahrain.

South Korea’s plans to (1) extend the duration of the job-seekers permit, (2) expand the type of jobs for which international students can apply, and (3) extend the amount of time job holders can remain in the country are to be put into effect in 2025.

For additional background, please see:

Source