An ordinary woman, a believer, kind and meek, of which there are many in Russia. She lived her life in labors and prayer. So what did she do to be executed by a firing squad?

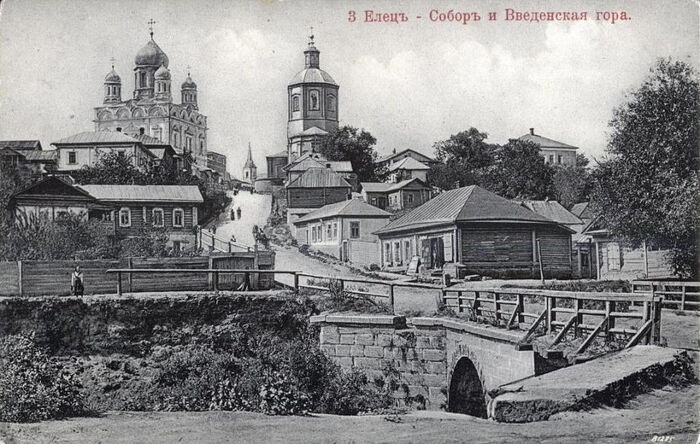

The city of Yelets in the Orel province—the saint’s birthplace

By the end of the nineteenth century, ancient Yelets, which had been a military outpost for centuries, turned into a cozy city of craftsmen and merchants with tall stone houses, factories and plants, schools and colleges, commercial buildings, a post and telegraph office, a theater, and a bank. Its main attractions were public gardens, buildings of local red bricks, monasteries and many churches, striking in their grandeur and beauty of architecture. By 1917, Yelets had two monasteries, thirty-one churches and fifteen chapels.

Ascension Cathedral and Vvedenskaya Hill, Yelets. Postcard, c. 1910. Pastvu.com

Ascension Cathedral and Vvedenskaya Hill, Yelets. Postcard, c. 1910. Pastvu.com

In 1889 in this city a daughter was born in the family of Nikolai Nikolaevich Ulyanov and was named Natalia. That year was marked by the consecration of the Holy Ascension Cathedral. However, there is no information as to where Natalia was baptized and which church she attended with her parents. The family was religious, God-fearing, united and respectful of knowledge and learning. Her father worked as a carpenter, which at that time allowed him to have a good smallholding.

The girl received her primary education in one of the parish schools, where they taught the Law of God, reading, writing, arithmetic, church singing and needlework: sewing, fancywork and the weaving of the famous Yelets lace. After graduating from school and before moving to Moscow, Natalia may have been a novice at the Convent of the Icon of the Mother of God “of the Sign” in Yelets, but this is just a guess.

In 1910, at the age of twenty-one, Natalia Ulyanova came to Moscow with the desire to enter the Novodevichy Stavropegic Convent. It seemed to everyone who entered that glorious convent as if they were in Paradise. To Natalia’s great joy, she was admitted as a novice. At  Russia’s nine most beautiful monasteries: Winter viewIf you’re not afraid of the Russian winter, here are nine reasons to visit the country in December and admire the view.

Russia’s nine most beautiful monasteries: Winter viewIf you’re not afraid of the Russian winter, here are nine reasons to visit the country in December and admire the view.

“>Novodevichy Convent she would perform various obediences for twelve years.

After the October Revolution

In 1917, the  The October Revolution: Prophecies on Russia’s DestinyWhy is this subject so important to us (and we must understand that it is of very serious importance to us) who may have nothing to do with Russians or Russia? Those who have ears to hear, let them hear; and those who have eyes to see, let them see.

The October Revolution: Prophecies on Russia’s DestinyWhy is this subject so important to us (and we must understand that it is of very serious importance to us) who may have nothing to do with Russians or Russia? Those who have ears to hear, let them hear; and those who have eyes to see, let them see.

“>October Revolution broke out, which not only disrupted the convent’s centuries-old established way of life, but jeopardized its very existence. In the first years after the establishment of Soviet power, by a decree of the Council of People’s Commissars the property of monasteries and convents was confiscated. So, everything they had became the “people’s”. The Decree of Nationalization strengthened this right. All actions against monasteries and convents were accompanied by repressions of clergy and monastics. In 1918, Novodevichy Convent was dissolved, but not yet closed. It would not be closed until 1922. And then the nuns would face the question: “What should they do and where should they live?”

Anti-religious agitation within the walls of the former Novodevichy Convent. Pastvu.com Monasteries and convents had various destinies. Fortunately, Novodevichy Convent did not become a concentration camp, but it was converted into the “Museum of the Reign of Princess Sophia and the Streltsy Riots”, later renamed the “Museum of the Emancipation of Women”. Then it became affiliated with the State Historical Museum. Some nuns remained at the convent and worked there as restorers and cleaners, helped in the churches which were still active, and read and sang in the choir. But many had to leave.

Anti-religious agitation within the walls of the former Novodevichy Convent. Pastvu.com Monasteries and convents had various destinies. Fortunately, Novodevichy Convent did not become a concentration camp, but it was converted into the “Museum of the Reign of Princess Sophia and the Streltsy Riots”, later renamed the “Museum of the Emancipation of Women”. Then it became affiliated with the State Historical Museum. Some nuns remained at the convent and worked there as restorers and cleaners, helped in the churches which were still active, and read and sang in the choir. But many had to leave.

From 1922 to 1930 Natalia Ulyanova worked in various Moscow churches. She sang in church choirs and helped in the churches. However, year after year there were fewer and fewer active churches in Moscow and in the countryside, so in 1930 she had to get a job at the Commercial Bank of Moscow, which was located on Ilyinka Street. Natalia Nikolaevna held modest positions as a courier and a cleaner at the bank for eight years.

However, in addition to her main employment (especially for believers like her), there was also compulsory labor. Lenin himself worked on a draft resolution of the Council of People’s Commissars on snow clearing, unloading potatoes and other types of “necessary work”. It was for people who were not engaged in “productive work” and for “non-working elements”. However, workers could also be conscripted for such work. Such cases were under the jurisdiction of the Main Committee for Universal Labor Service.

Natalia Nikolaevna was sent to clear snow on the railway and to do difficult seasonal work on peat cutting near Moscow. In the 1930s, peat was needed for the construction of the Moscow–Volga Canal. There were power plants on it, including the Shatura plant. There was an acute shortage of workers for peat extraction.

Life in a monastic “communal apartment”

After its closure, Novodevichy Convent was turned not only into a museum, but also into a residential quarter in which people were housed in towers, monastic cells, and hospital wards. The children’s writer Viktor Suteyev lived in the Setun Tower, and Count Vasily Sheremetev in the Naprudnaya Tower. The artist and architect Vladimir Tatlin opened a workshop in the bell-tower. Some had five-room apartments, others huddled together in cold closets downstairs. Some residents used icons to make their dwellings comfortable, while others saved holy images from destruction. Natalia Ulyanova, the convent’s former novice, lived in one of the former cells. She would write her address in questionnaires that she filled out when applying for a job: “Moscow, Pirogovskaya Street, 2-15-69 (on the territory of Novodevichy Convent)”.

Different people lived in the huge “communal apartment”. Some of them were former nobles or nuns. But many of the residents hated nobles and monastics, and therefore were happy to give false testimonies in order to get rid of the vestiges of the hated past. So, a false denunciation was concocted against Novice Natalia Ulyanova.

Arrest

Natalia Nikolaevna was arrested on March 11, 1938 and brought to police station number 7 in the Frunzensky district of Moscow. A few days before, some people, whom she had never harmed in any way, signed their testimonies against her. A document had been drawn up by the investigator in advance. The thoroughly elaborated mechanism of denunciations and perjury worked almost without failures. During the interrogations, Natalia Nikolaevna was reminded about words she had allegedly said two years before on a patch of land beside the monastic cells.

“As an individual hostile to the Soviet Government, she told her neighbors that there would be no point in collective farms if people working on the land lived from hand to mouth.” According to the investigator, these words contained slander against collective farmers, provocation and fabrications about “honest and glorious collective farm labor” in the USSR and a “bright future”. They declared it “counterrevolutionary activity”.

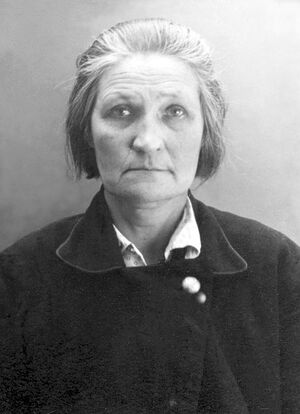

Inmate Natalia Ulyanova. Moscow, NKVD prison, 1938 On March 13, a confrontation with witnesses was arranged. Natalia Nikolaevna admitted neither perjury nor the charges brought against her and stated, “I did not conduct any agitation among the people in Novodevichy Convent concerning the life of collective farm peasantry.” But did anyone really need the truth, her truth?…

Inmate Natalia Ulyanova. Moscow, NKVD prison, 1938 On March 13, a confrontation with witnesses was arranged. Natalia Nikolaevna admitted neither perjury nor the charges brought against her and stated, “I did not conduct any agitation among the people in Novodevichy Convent concerning the life of collective farm peasantry.” But did anyone really need the truth, her truth?…

Prosecution and sentence

The charge brought against Natalia Nikolaevna Ulyanova, a forty-nine-year-old former novice of Novodevichy Convent, was as follows: “Counterrevolutionary agitation, slanderous provocative fabrications about the life of collective farm peasantry, counterrevolutionary activity among the residents of the house she lived in.”

On March 15, the troika at the UNKVD (the Directorate of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) in the Moscow region passed sentence: the death penalty—execution by firing squad. On March 22, 1938, the sentence was carried out at the Butovo firing range. The novice nun’s life was destroyed within two weeks. She was interred in a mass grave.

In August 2001, by decree of the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church, Natalia Ulyanova was canonized and her name was included in the  New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia

New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia

“>Synaxis of the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church.

Icon of the New Martyrs of Novodevichy Convent She is commemorated on March 22, on the Synaxis of the Saints of the Voronezh Metropolia, as well as in the Synaxes of the Saints of Lipetsk and Moscow, in the Synaxis of the New Martyrs Who Suffered in Butovo, and in the Synaxis of the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church. Since 2006, with the blessing of Patriarch Alexei II of Moscow and All Russia, Novodevichy Convent has celebrated an annual feast of the Holy New Martyrs and Confessors of the convent on the Saturday before the

Icon of the New Martyrs of Novodevichy Convent She is commemorated on March 22, on the Synaxis of the Saints of the Voronezh Metropolia, as well as in the Synaxes of the Saints of Lipetsk and Moscow, in the Synaxis of the New Martyrs Who Suffered in Butovo, and in the Synaxis of the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church. Since 2006, with the blessing of Patriarch Alexei II of Moscow and All Russia, Novodevichy Convent has celebrated an annual feast of the Holy New Martyrs and Confessors of the convent on the Saturday before the  Sunday of the Myrrh-bearing Women

Sunday of the Myrrh-bearing Women

“>Sunday of the holy Myrrh-Bearing Women. Among them is the Venerable Martyr Natalia (Ulyanova).

In the same year, at the request of Metropolitan Juvenaly of Krutitsy and Kolomna, an icon, “The New Martyrs of Novodevichy Convent”, was painted. It depicts the holy Priest-Martyr Sergei Lebedev and the Nun Martyrs Natalia (Ulyanova), Irina (Khvostova), Matrona (Alexeyeva) and Maria (Tseitlin).