Category: Politics

-

Archbishop Wale Oke’s Track Record Shows He Has Robust Capacity To Lead PFN For 2nd Term – Isong

Archbishop Dr. Emmah Gospel Isong, is National Publicity Secretary, Pentecostal Fellowship of Nigeria PFN who knows his onions as far as issues of PFN are… Read More

-

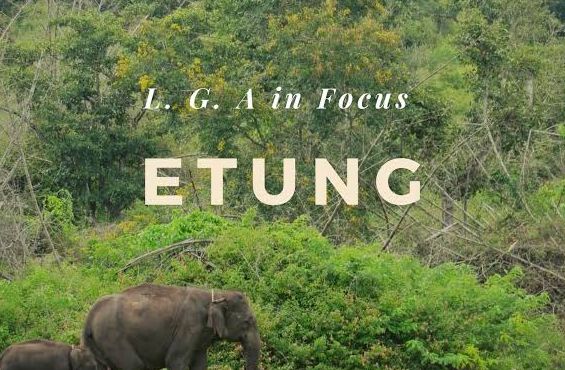

Councillors cry foul as chairman allegedly hoards revenue agencies in Etung

Elected Councillors in Etung Local Government Area have expressed their dissatisfaction over the sharing formular of revenue agencies across the 10 wards. The 10 councilors… Read More

-

PMQs verdict: Kemi Badenoch, belatedly, picks the right battle

In response to the prime minister’s press conference yesterday, Kemi Badenoch said she welcomed a public inquiry into the Southport murders but added — in… Read More

-

‘We’ve got to move on’: Rachel Reeves rejects calls to negotiate UK-EU customs union

Ministers have rejected calls for the UK to move closer to the EU in order to boost economic growth, insisting that Brexit has brought “opportunities”… Read More

-

Keir Starmer sends clear message to critics over Southport aftermath

Rarely in politics or public life does a “first test” — that media expression referring to an early, unexpected event — prove so definitive in… Read More

-

‘Government has questions to answer’ about Southport attack aftermath, says Philp

A senior Conservative frontbencher has said the government must reveal “what they knew and when” about Southport killer Axel Rudakubana, who pleaded guilty on Monday… Read More

-

The Politics of Yakurr: A Shift in Loyalty and Leadership

By Enang Eja The unfolding dynamics in Yakurr’s politics bring to mind the tale “How the Cookie Crumbles,” a childhood story my father often… Read More

-

Keir Starmer says Southport murders ‘must be a line in the sand’ — full statement

Keir Starmer has delivered a statement from Downing Street on last summer’s knife attack in Southport, which left three young girls dead Axel Rudakubana, 18,… Read More

-

‘Britain will be one of the great AI superpowers’ — Keir Starmer’s technology speech in full

The roll out of artificial intelligence will be “the defining opportunity of our generation”, Keir Starmer has said. In a speech in east London dedicated… Read More

-

Rachel Reeves is trapped

Economic growth is flatlining, the pound is down, gilt yields are up, borrowing costs continue to rise — and Liz Truss is claiming total vindication… Read More