By 2041, experts expect that the number of domestic high-school graduates in the US will drop by 13%. This is due in large part to a projected steady decline in the 18-year-old cohort beginning in 2025. This so-called “enrolment cliff” stems from a weakening fertility rate among US women over the past few decades, as couples weigh the pros and cons – e.g., financial, lifestyle-related, environmental – of having children. It fell to an all-time low in 2020 and was less than half the rate observed in 1957.

The shrinking pool of domestic students is expected to present huge challenges for some colleges (e.g., smaller ones whose quality is not captured in rankings) and to be less of an issue for highly selective colleges. It is also expected to hit certain states and regions more than others, with the South the only area of the US where the pool of 18-year-old students is expected to increase in coming years.

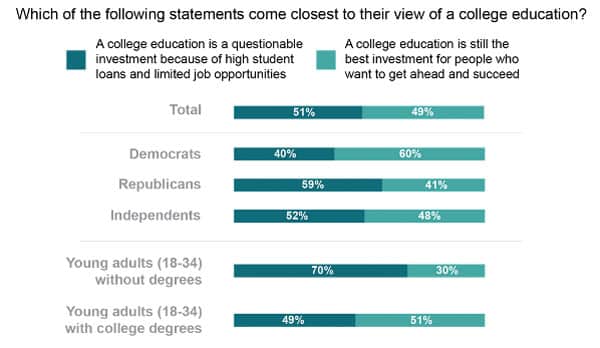

The dynamic is exacerbated by a growing sense in the US that higher education does not always provide enough of value relative to its cost. Among those who cannot get into and afford a highly selective college, direct entry to the workforce is an increasingly popular option.

Shorter, less expensive options on the rise

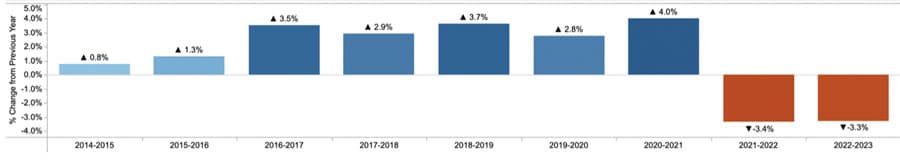

Another appealing option for many high school graduates is skills acquisition via certificate or micro-credential. National Student Clearinghouse Research Center released a report in April 2024 that found that the largest segment of certificate-completers during the 2022/23 academic year was 18-20-year-olds. By contrast, in 2022/23 “fewer students earned an associate degree than in any of the last ten years, and bachelor’s earners declined to their lowest level since 2015-16.”

The report found that:

- Of all programme completers in 2022/23, 19.5% graduated with a certificate, 24.1% graduated with an associate’s degree, and 56.4% graduated with a bachelor’s degree.

- The number of students who progressed from one credential to another fell, and this was mainly because fewer students are completing an associate degree and then progressing to a bachelor’s degree.

Worry is natural, but it isn’t enough

The projected enrolment cliff – and data on showing the ebbing attraction of degrees – is naturally alarming for many educators. There is a widespread belief that school and programme closures are inevitable, especially for smaller schools and for humanities-based departments. But many industry analysts are arguing for less resignation and more strategic thinking.

For example, Nathan Grawe, an economist and professor at Minnesota-based Carleton College, told Inside Higher Ed: “People shouldn’t wish away the real challenges of the situation … but while resignation is not the right response, neither is fear.”

He continued:

“If we choose to continue as if it’s just business as usual, I don’t know how colleges could expect to not see major enrollment declines. The good thing about higher education is we have an enormous lead time to try doing things differently—it’s not as if birth rates dropped 17 percent in one year. We just have to choose to put ourselves on a new path.”

Laura Bloomberg, the president of Cleveland State University, was also interviewed and said that her university laid off staff this year due to enrolment declines and a US$400 million deficit. She noted that her institution is not alone in having clung to an overly optimistic perspective:

“This is happening all over the country, and that’s because we budgeted based on hope. Hope is great, but it isn’t a strategy. Some people might call that the tyranny of low expectations. I think it is accepting the demographic reality of the region and focusing on putting our energy where we can make a difference.”

So: what could make a difference? What can colleges do other than resign themselves to programme closures and staff reductions?

They can approach recruitment and operational priorities in fresh ways. For example, they can:

(1) Identify new domestic recruitment targets. In a report released by the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE), president Demarée Michelau notes: “There are still plenty of potential students out there, including recent high school graduates who historically haven’t been well-served by our education systems, those who may be leaving college short of a degree, and adult learners, including those with previous college experience.”

(2) Adopt student-centric strategies. Institutions can shift budget allocations to focus on student services and retention strategies, and encourage students to progress from one level to the next. They can also add more flexibility into degree programmes and expand blended and distance programme delivery to capture a larger segment of students.

(3) Reimagine branding. Rankings are not everything. In fact, they have lost importance relative to graduate outcomes and value for money over the past several years. Schools should explore what they are best at, how they can communicate these strengths, and strengthen connections with employers. Students are much more likely to attend a less selective college if there is proof that its programmes lead to desirable jobs.

(4) Invest more in international student recruiting and hosting. This means expanding the focus well beyond India and China. At Lynn University in Boca Raton, Florida, the international student population makes up 17% of all enrolments, but China and India do not appear the school’s top five markets. Renee Loayza, the director of international admission, told NAFSA’s International Educator magazine: “We’ve found success focusing on regions such as Latin America, the Caribbean, and Europe to build strong, personal relationships with students and parents … having high school counselors and educators who know Lynn is crucial for navigating these complex markets.”

Ms Loayza’s comment speaks to the importance of a “best-fit” strategy in international recruitment. This approach prioritises quality over quantity of student, and it relies on an investment in data systems (e.g., CRM) and top-quality agents and other partners to communicate competitive advantages to the students most likely to succeed at the institution.

NAFSA CEO Dr Fanta Aw says:

“We do believe there is ample capacity at U.S. colleges and universities to welcome international students. However, institutions must be committed to creating the structures, systems, and environment for them to thrive. That starts with approaching international students with the right motivation and perspective—to see them as true assets to the campus, classroom, and community on a multitude of levels, not to simply plug a gap in enrollment or tuition dollars.”

Carleton College’s Nathan Grawe adds:

“We shouldn’t think of it as a light switch, like everybody wants to study in the United States, so, if we need to, we’ll just flip that switch. We’re going to have to work for it.”

For additional background, please see:

Source