A new report asserts that there is no basis for blaming international students for the lack of housing (and lack of affordable housing) in Australia. Research commissioned by the Student Accommodation Council, a peak body for the country’s purpose-built student accommodation sector (PBSA), found no alignment between the return of international students to Australia – after borders reopened post-pandemic – and rents increasing.

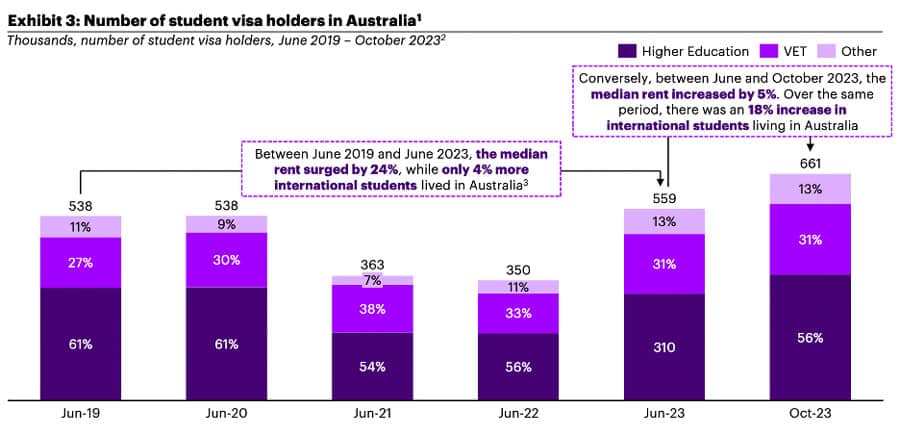

Instead, says the report, entitled Myth busting international students’ role in the rental crisis, “rents began rising in 2020, when there was no international student migration and most students had returned home.” There is data to back the point: “Between 2019 and 2023, median weekly rent increased by thirty per cent. Over the same period, student visa arrivals decreased by 13%.”

Student Accommodation Council executive director Torie Brown writes in the report: “International students have been unfairly blamed for the rental crisis, yet this report shows that long-term structural issues in Australia’s housing market are the real cause for rental pressures.”

The research found that international students make up only 4% of all renters in Australia. Domestic students compose 6.2%, and the remainder are non-students. What’s more, the vast majority of international students do not live in the housing most in demand in Australia. Only 3% live in detached houses suitable for couples or families, while 74% live in PBSA close to universities.

The Student Accommodation Council attributes the housing crisis in Australia to “a complex web of supply and demand drivers …. including the rise of smaller and solo-person households, intrastate migration, rising construction costs, planning delays and a trend to re-purposing second bedrooms into home offices, amongst others.”

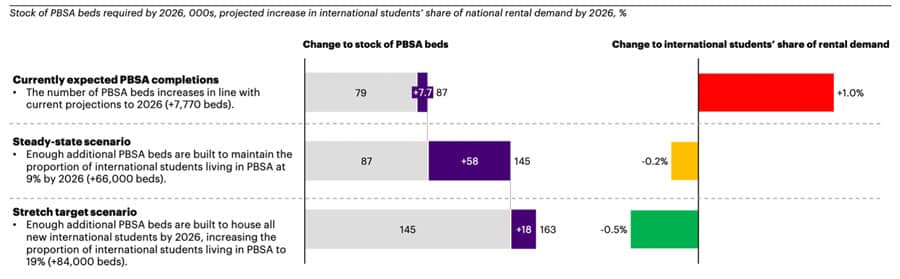

Now that international students have returned, however, there is a great need for increasing the supply of purpose-built student accommodation (PBSA). Vacancy rates in major Australian cities are currently around 1%, and rental prices have been climbing for months.

Unfortunately, the Student Accommodation Council says that looking at the pipeline of new PBSA currently (7,770 new beds), there will not be enough supply to ease pressure on the rental market from international students by 2026. That would only be accomplished if there were 84,000 beds ready by that time.

A key issue undermining progress at getting enough accommodation built, says the report, is cumbersome approval processes that delay completion of projects.

Go8 research echoes the findings

Separate research by the Group of Eight (Go8), which represents Australia’s leading research-intensive universities, also lays the blame for the housing crisis on supply-side issues, rather than excessive demand from international students. The policy paper, International students and housing and other cost of living pressures, argues that no matter how many international students were provided with visas, current supply chain dynamics dictate that there would still be a housing crisis.

Go8 Chief Executive Vicki Thomson writes:

“The number of international student arrivals has no direct bearing on underlying supply side factors which include decades of underinvestment; Government regulation, planning approvals, elevated construction costs and workforce shortages; supply chain disruptions; and weak productivity growth. Any plans to impose a cap on international students as one mechanism to ease housing pressure – especially during a domestic skills crisis – is short-sighted and risks putting a brake on Australia’s economic growth and prosperity.”

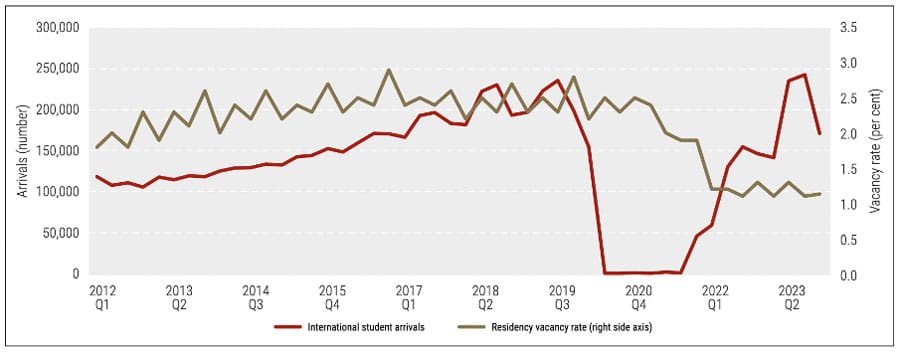

Like the Student Accommodation Council’s report, the Go8 report charts data underlining the myth that increasing volumes of international students over the past few years correlates with lower residency vacancy rates.

Ms Thomson encourages the government to consider how much international students contribute to Australia’s prosperity – a 0.8% increase in GDP in 2023 is directly attributable to these students:

“We caution against apportioning blame to one cohort of students who were responsible for most of the nation’s economic growth. In 2023, following a downturn during the COVID-19 pandemic, total spending by international students bounced back to $47.8 billion. International students contributed an 0.8 per cent increase in GDP over 2023 (more than half of the recorded 1.5 per cent economic growth) according to the National Australia Bank.”

The Go8 report concludes by saying that a Canada-style blanket-cap on new international student visas is not the way forward:

“If the Australian Government’s resolution is that net overseas migration numbers must be eased, a blunt instrument such as immediate caps on international students attending Australian universities is not a smart solution as already outlined.

The Go8 does support targeted interventions to tackle “ghost colleges and visa factories” together with strengthened English language requirements for visas to ensure the integrity of Australia’s (international) education and migration systems.”

For additional background, please see:

Source