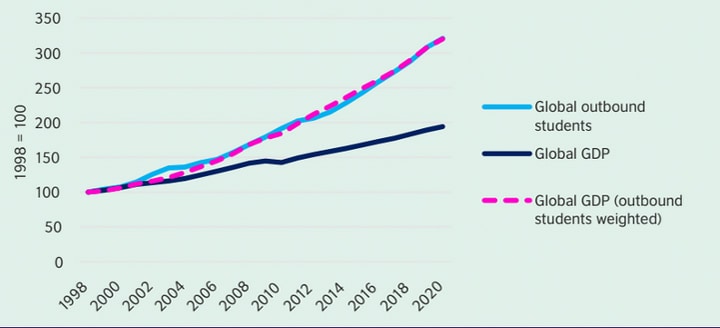

A new study suggests there is a strong link between global GDP growth and outbound student mobility levels, and that this correlation will lead to slower total outbound mobility growth through 2030 compared to the previous two decades.

The study report, The outlook for international student mobility: amidst a changing global macroeconomic landscape, was conducted by Oxford Economics and commissioned by the British Council. The study analysed 30 sending markets.

The GDP growth–outbound student mobility association is a new indicator, but analysts say that when applied to previous years, it lines up with UNESCO mobility data from the past – and therefore is a solid indicator of upcoming trends.

They illustrate the strength of the association with this example:

“Although global outbound student volumes have never declined on a year-on-year basis since UNESCO records began, significant slowdowns in growth were seen in 2003/04 and 2011/12. Both these periods of sharp slowdown occurred 1–2 years after significant global economic slowdowns (Dotcom Crash and Global Financial Crisis), suggesting a lagged passthrough from economic shocks to outbound student volumes.”

And at the country level, they note:

“Countries which have recorded the strongest growth in outbound student numbers [in the 1998-2020 period] have had amongst the fastest growing economies (e.g. China, India, Vietnam, Bangladesh), with slower growing economies like Japan, Hong Kong (SAR), Spain and Canada amongst the slower growing outbound student markets.”

Weaker “but still robust” growth ahead

In the two decades leading up to the COVID-19, global outbound student mobility increased at an average annual rate of about 5.5% per year. The Oxford Economics study predicts that this rate will slow to 4.2% up to 2030.

Slower growth does not mean zero growth, however; there is still great potential for students to choose to study abroad over the next few years and the British Council describes the next phase of mobility as “modestly weaker but still robust.” However, the slower growth means “student recruitment will depend on a more strategic approach to targeting of markets and allocation of resources.”

Macroeconomic volatility dampens growth potential

At the country level, the principal drivers of student mobility are economic growth, household income, and stable exchange rates. The impact of that last driver has been particularly notable in Nepal, Nigeria, and Vietnam. Exchange rate volatility in those countries has led to uneven outbound mobility trends in the past and highlights just how much uncertainty is created when a country’s currency declines, as was the case this past year in Nigeria.

British Council researchers write that economic growth and household income are medium-term predictors of outbound mobility, while changes in exchange rates have a more immediate impact.

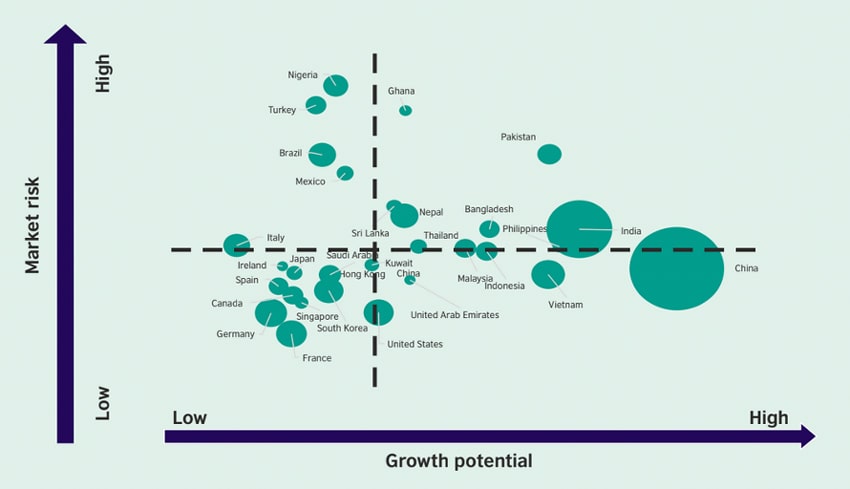

To predict outbound student mobility, the Oxford Economics analysts considered the growth potential and macroeconomic risk profile of individual sending countries, as shown in the chart below. (The report notes that the size of the bubble represents the number of outbound students in 2020 or latest available year).

Only Brazil and Pakistan are expected to have a mobility growth rate higher than what it has historically been, though Bangladesh, Indonesia, Philippines, and Vietnam are also expected to remain growth markets at a global level.

Mobility rates will decline in the key markets of China, India, Nigeria, and Indonesia. In particular, the growth rate from China will slow dramatically:

“The annual average rate of growth [in China] is expected to more than halve from around 18 per cent per year in the decade prior to the pandemic, to around 8 per cent per year in the 2019-30 period.”

That said, China and India will continue to the top sending countries through this decade, and in absolute terms, mobility from these countries continues to rise. China and India are relatively low risk compared with emerging markets, and their macroeconomic conditions are “supportive of growth in outbound student mobility.”

The mobility growth rate will decline in advanced economies such as Canada, France, Germany, Hong Kong (SAR), Ireland, Italy, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, and Spain – but the British Council emphasises the value of these markets in terms of stability and diversity in an overall student population.

Intense competition is expected in Brazil, Ghana, Mexico, Nigeria, and Turkey – because of a complicated mixture of demand for study abroad and macroeconomic pressures making it difficult for some families to send their children abroad. The British Council notes: “They will remain important recruitment markets for the UK to 2030, though primarily by winning market share from alternative study destinations.”

Bangladesh, Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam are considered “rising stars” thanks to their “favourable macro environments and low/moderate risk profiles.”

Kuwait, Malaysia, Nepal, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, UAE, and the US also offer important recruitment opportunities because of low/moderate market risk levels – but the analysis found they have less potential for growth. The British Council says the opportunity in these countries lies in their ability to contribute to “a balanced portfolio of student recruitment markets,” and notes that “several of these countries offer generous government funded scholarship programmes.”

For additional background please see:

Source