“The Path of Holiness Is Never Closed to Anyone in Any Circumstances”A real Christian remains one everywhere—in everyday life, in communication with a stranger; a seller or a buyer, a boss or a subordinate. For a Christian everything is subordinated to the same Gospel law, which is the basis of his spiritual life.

“The Path of Holiness Is Never Closed to Anyone in Any Circumstances”A real Christian remains one everywhere—in everyday life, in communication with a stranger; a seller or a buyer, a boss or a subordinate. For a Christian everything is subordinated to the same Gospel law, which is the basis of his spiritual life.

“>Part 1

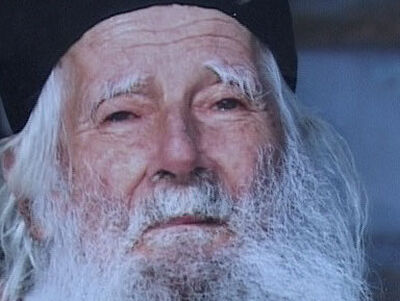

Priest Alexei Shishkin

Priest Alexei Shishkin

The Path to the Priesthood

—How did you decide to devote your life to the priestly ministry?

—I can’t say that once I woke up and decided to become a priest. It was the development of my worldview and the establishment of my soul. During the period of my integration into Church life, I studied at the university. At the same time, I thought of entering a theological college and even study full-time. And in my fifth year at the university, where I studied to be a programmer, I had a feeling that I should venture to enter a theological school. When I told my father-confessor, Father Pyotr Mashkovtsev, about this, he gave me his blessing and said: “Give it a try.”

However, at that time it was not certain yet that the choice had been made and my life path was the  “The Priesthood is the Most Terrible Thing on Earth”Even if I had graduated from all the schools of this world, even the highest schools, not a single one of them would have been as useful for me as the school of sufferings.

“The Priesthood is the Most Terrible Thing on Earth”Even if I had graduated from all the schools of this world, even the highest schools, not a single one of them would have been as useful for me as the school of sufferings.

“>priesthood. There are so many intermediate stages on the path to the priesthood, and each of them can turn in a different way. It may turn out that you are spiritually unprepared or unworthy. And one of the stages was my admission to the seminary. At that time I was free—I was single, I had no children, no divorces, did not have to pay alimony, so why shouldn’t I try? Father Pyotr Mashkovtsev signed the reference letter, and Metropolitan Chrysanth (1937–2011) of Vyatka and Pokrovsk signed it. After that I went to Moscow and enrolled in the theological seminary.

And then a new stage began: a seminarian is supposed to find a good young lady for marriage with whom he can build a happy family, and everything should turn out well so he can apply for ordination. And, as I can tell you now, everything worked out for me.

—Did you and your future wife first meet at the theological school? How did it happen?

—It’s very simple. The seminary has several hundred students who want to become priests, and about 100 girls. Some of them study at the Choir Directing Department and some at the School of Icon-Painting. The girl I took the fancy for studied at the School of Icon-Painting—she embroidered icons. And our acquaintance was ordinary to the point of banality. Before classes I kept walking and looking. At last I saw her walking alone, ran up to her, but she said, “Later, later.” She was in a hurry—that is, there was no beautiful romantic story at that moment; rather, the fateful meeting was ordinary, banal and very short: she was late for her classes. And I thought: “If I come up to her again and something like this happens again, then we aren’t destined to become a husband and a wife.” I came up to her again, and this time she reacted normally. We got to know each other better and then got married.

—What spiritual and life lessons did you learn over the years at the capital’s theological school?

—If we talk about the essence of studying at a theological school, a seminary is a place where you are tested: not even before the Church, but for yourself—whether this is your path, even of the priesthood. A seminary is an institution where there are many obediences, theological subjects, and practically a barrack atmosphere—that is, in terms of discipline the structure of life resembles the army. However, now they have built a good dormitory there, where two seminarians share a room, and sometimes one seminarian lives in a separate room. When I studied, our dormitory was beneath the royal chambers—it used to be a stable. And part of the dormitory consisted of large rooms, in each of which fourteen to sixteen seminarians lived, but at the moment when I entered the seminary a couple of “chambers” were being renovated, and the large rooms were crammed with beds, with only narrow spaces between them. Over twenty seminarians would live in each of those rooms—that is, we were cooped up there. There were two or three shower cubicles and five or six sinks for 100 students. But I took such harsh conditions quite calmly; apparently, the question of the “barrack” situation did not depress me and did not cause inconvenience.

Thus, the seminary became a test for its students: whether you need it or not, whether you can stand it or not, whether you agree with it or disagree. There were a lot of disciplinary moments; there were moments when you were scolded or treated unfairly, and you had to accept it. There were many moments when you interacted with other seminarians. A seminary is a test of how much you need the church ministry, because it is not easy there. The Church is not a community of saints; rather, it is a hospital where sinners repent.

And to expect that we will become “wonderful” people here, and that everything will be like in Paradise, that we will come and meet hosts of saints here, and they will make us saints too—nothing like that! We are here in a community of sinners trying to reform, and it is very hard to say whether they succeed or not. Some make good progress, others are less successful, others manage very poorly, and others don’t even try to improve and only pretend—and it shows in them. And we all live in this community. So, a seminary is a test of whether you are able to accept a lot, bear it, whether or not you need it and sincerely want to go further down this path; because the higher you move up the ranks in the Church hierarchy, the more vividly you see this and encounter it face to face.

When a person is at some distance from the Church in a good sense—that is, he does not perform church obediences and does not work in the Church—he comes to church, prays, confesses his sins, takes Communion and leaves, or also does some good deed and reads the Gospel, he is not involved in the inner church life, and this distance can give him freedom. It allows him not to immerse himself in Church relationships. And someone who gets into the church hierarchy—a seminarian, a deacon, a priest, and even more so a bishop—he immerses himself in it completely, and he must live with it all his life. And I cannot say that this process is very easy.

For many, staying at a distance from the Church is even a great blessing—because, for example, one may have a strong sense of justice, lack patience or humility in situations where he cannot abstract his mind from it. He can’t put up with something, but it’s also hard to stand it. He can’t leave, because, for instance, he is in the ordained ministry, but he can’t bear it either, and the person has an inner dissonance—he feels bad.

At the same time, the  “Why Go to Church If I Have God in My Heart?”Today one can often hear the phrase: “Why go to church if I have God in my heart?” It would seem that one could only envy this person. True, if God is in your heart, then church-going is seen as something quite unnecessary.

“Why Go to Church If I Have God in My Heart?”Today one can often hear the phrase: “Why go to church if I have God in my heart?” It would seem that one could only envy this person. True, if God is in your heart, then church-going is seen as something quite unnecessary.

“>Church is a Divine and human organism that God created to guide man to salvation. And, on the one hand, if a person can abstract his mind from the internal problems of the Church, it is good for him. On the other hand, if a person is ordained, he is inside all the problems, but the grace that he receives from God cannot be compared to anything. Priests value their ministry very much, because the priesthood is an invaluable gift that is given to a man, and it is also the greatest blessing. So they have more problems, but the grace that a person receives in the ordained ministry is greater. And if one thing is made up for by the other in a person’s inner world, it means that he will live in the Church in harmony. But if it does not work out, he does not receive grace, and perceives all these internal Church problems too painfully, then he may have an inner dissonance. And I want to say that most priests remain in the priesthood and are quite happy, which means that they live in harmony inside the Church.

Priest Alexei Shishkin with family

Priest Alexei Shishkin with family

A priest’s children

—How is faith manifested in your family’s everyday life? How do you plant church traditions in your children?

—I don’t think it is especially or vividly manifested in my family. We pray a little in the evening, pray in the morning, pray before eating; every evening I read books, including a children’s Bible, we may discuss some matters, but in general, I can’t say that my children are very different from other children. We have very ordinary children: the only difference is that their father is a priest, and their mother is a priest’s wife. We pray, take Communion, confess our sins, and talk a little about God.

It varies in different religious families: everyone has their own approach. Some try to make super-religious people out of their children from an early age, others are even negligent about this. I personally try to find a happy medium, because if I am overzealous, I feel that nothing good will come from excessive moralizing. But it is also wrong to ignore the Christian aspect of education completely. Therefore, I try my best not to nag on religious matters and not to annoy my children very much.

This theme raises the question of what an Orthodox Christian should be like in certain circumstances. He must be Orthodox: an Orthodox Christian on a trolleybus, an Orthodox walking down the street, an Orthodox entering a church, an Orthodox working. What makes him different from other people is that he makes efforts to fulfill the commandments of God, to pray, and to turn to God with his heart. Therefore, the upbringing of children in an Orthodox Christian family, including a priest’s, may not differ much from childrearing in ordinary families. There are simply some spiritual aspects: reading the Bible, prayer, and the participation of children in the Church sacraments. Otherwise, they live a very ordinary life. Maybe now something new will be introduced into our family—a more in-depth knowledge of faith—since our two eldest sons are studying at the Vyatka Orthodox school. But it is an ordinary municipal school with an Orthodox bias in education and subjects, and it does not have a system like in a theological seminary with its many services and obediences.

“I make efforts, and God helps me”

—What helps a Christian on the path of spiritual growth?

—God. In general, it is an attempt to be a Christian, to do what God tells you to do. I make efforts—and God helps me.

During the hierarchal service at the Church of the Nativity of the Most Holy Theotokos

During the hierarchal service at the Church of the Nativity of the Most Holy Theotokos

—Tell us about your pastoral ministry at the Church of the Nativity of the Mother of God. Are many parishioners eager to listen to the Word of God?

—At the church in Chistye Prudy in the city of Kirov, where I serve as a priest, I have been teaching at the Sunday school for adults since last year. And this year we resumed classes towards the end of September. The classes are mostly attended by people closer to middle and pre-retirement age. Last year we discussed the Gospel. This year, a curriculum including the Knowledge of God will also be offered. Adults will be able to read both the Gospel and the commentaries to it on their own—my involvement here is not very important. But there is one aspect that is very lacking in the Church today: communication with a priest. But this is very important for people. Someone needs to ask a question, resolve some perplexity, and the very presence of a priest near those for whom he is responsible is very good. So I see this important moment in the role of a Sunday school for adult parishioners.

Priest Alexei Shishkin holds a tour for Orthodox psychologists

Priest Alexei Shishkin holds a tour for Orthodox psychologists

On the one hand, meetings are devoted to talks on spiritual topics: I explained the commentaries to the Holy Scriptures—I tell them what I know. At the same time, a number of parishioners may know the Gospel better than I do, they may read more commentaries than I do, and they may surpass me in spiritual life. But they don’t “hurt my self-esteem” by it at all; if a person strives for holiness, this happens. However, a priest is someone who is appointed by the bishop, the Church and God Himself to teach parishioners, so to be able to communicate with him is good.

A priest can look at this or that disturbing situation as someone who has encountered other similar stories in his pastoral practice, as someone who can say something edifying. Therefore, in the classroom we first talk about the Gospel, discuss something, and then communicate, reflecting on everyday problems or some situation that requires a resolution. In my opinion, it is very useful to think aloud about how to act wisely in a Christian way for the benefit of yourself and others.

Communal prayer at the Church of the Nativity of the Theotokos. A hierarchal service

Communal prayer at the Church of the Nativity of the Theotokos. A hierarchal service

—What works of art, including literature, documentaries and feature films, can you recommend as useful for the soul?

—Spiritual reading begins with the  Living the Gospel Is the Best PreachingThe Lord puts the fulfilment of the commandments first.

Living the Gospel Is the Best PreachingThe Lord puts the fulfilment of the commandments first.

“>Gospel.

After the Gospel, I would recommend reading the Catechism, a reference book that contains a simple confession of faith—it helps us realize Who we believe in. And then you can read moral literature. The classics of moral literature are those written by Abba Dorotheos of Gaza: a small yet excellent book in all respects and easy to read; and very similar to it in many ways is the Ladder of Divine Ascent by St. John Climacus. When I first read it, it seemed complicated to me, but later I really liked these books. But it does not mean that you must necessarily read precisely these books and in this order. People come to faith in different ways through reading spiritual literature, they read different books. And yet, if you read the Gospel, the Catechism and the instructions of Abba Dorotheos, a certain foundation will be formed, and then you can continue to study the Holy Scriptures, including the Old Testament, the Acts, the Epistles, the Revelation of John the Theologian, commentaries and moral literature.

Further, if you are interested, you can study dogmatic and moral theology. The Law of God by Archpriest Seraphim Slobodskoy can serve as an Orthodox reference book on your shelf.

As for cinematography, I really like the movie The Island.

Church of the Nativity of the Theotokos in Kirov

Church of the Nativity of the Theotokos in Kirov

Miracles are in small things

—Do you believe in miracles?

—I don’t see any colorful miracles in my life. Rather, I hear about them more often than I experience them. I usually see miracles in small things, and I must be able to notice them. I have woken up today, I am alive, my eyes can see, my feet can walk: isn’t it a miracle? When someone is looking for some remarkable, extraordinary miracles and does not see simple ones, I believe it is a bad sign. And if we take our whole life, I see a miracle in this: if you do not try your best to fulfill your own will, but humble yourself and accept the will of God, then (not always, but often), looking back, you can say, “Wow, what wonderful Providence of God! One, two, three, and dozens of circumstances were linked together in one line, and half a lifetime has been built thanks to them.” As you look at it you think: “Truly this is Providence.”

—But man is free. And in any situation you make a choice, which probably becomes good for your later life.

—There is the will of God which creates good, and there is the will of God which allows. If I sin, isn’t it God’s will, because God allowed me to sin? If I have sinned, it means that there was God’s will here in some sense, but it was the will which allows. And there is the will of God which creates good: if God commands to do something and I do it. And when I talk about linking together that number of circumstances that I may not even have dreamed of before, but they unfold, and I get a life like this, and it’s beautiful and wonderful. But, doing each individual deed, it was impossible to predict what it would lead to, but it has led to what it is now, and it is good for me. Maybe I’m speaking very abstractly.… If I put it in a nutshell: if you try to live a holy life, you see the will of God, which is fulfilled in the most wonderful way.

Strive for holiness

—What would you wish our readers?

—When it comes to saints, people often say, “This is not about us—we aren’t saints.”

You know, we are not saints for one simple reason—we don’t want to be saints; that’s all—there are no other special reasons. Therefore, I want to wish you not just abstract holiness, but the desire to be saints. Clearly, everyone has different measures: the measure of holiness of St. Seraphim of Sarov is not the same as ours. But we must not justify our unwillingness to live according to the will of God by saying that we are not saints. Everyone can (as much as they want) try to succeed in this. True, it’s unlikely that any outstanding results will come soon, but anyone can strive for holiness, anytime and in any circumstances. It just requires effort.