FAST FACTS

Capital: Islamabad

Population: More than 250 million (2024)

Youth population: Two-thirds of the population is under 30

Median age: 20.5

GDP: US$375 billion (2024)

Currency: Pakistan rupee (PKR)

Official languages: English and Urdu

Main language of instruction: English (especially in private schools) and Urdu (especially in public schools).

English proficiency: “Low” according to the EF Proficiency Index, and 10th of 23 countries in Asia.

Religion: Islam

Geography: Pakistan is in South Asia. It shares borders with Iran to the west, Afghanistan to the northwest and north, China to the northeast, and India to the east and southeast.

Outbound students: Over 100,000

Preferred destinations: UK, China, UAE, Australia, US, Malaysia

Top student cities: Lahore, Karachi, Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Faisalabad, and Peshawar

Pakistan is becoming an increasingly valuable recruiting ground for educators in leading destinations. A large segment of high-school and college-aged Pakistani students are interested in study abroad, and nearly half of Pakistan’s population is under the age of 20.

Market fundamentals

The market fundamentals are in some ways very strong. According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Pakistan’s youth demographic is the largest in the world. Nearly two-thirds of the population is under the age of 30.

Pakistan is third, after only China and India, in terms of the size of its college-aged population. The British Council expects growth in Pakistani outbound mobility to be among highest in the world over the next decade, along with China, India, Nigeria, and Bangladesh.

Unfortunately, Pakistan is also a country where there is massive income inequality and limited opportunities for youth. The Commonwealth’s Youth Development Index for 2023 found that in South Asia, Pakistan is one of two countries that ranks “low.” WENR has written:

“Failure to integrate the country’s legions of youngsters into the education system and the labour market could turn population growth into what the Washington Post called a ‘disaster in the making … putting catastrophic pressures on water and sanitation systems, swamping health and education services, and leaving tens of millions of people jobless’—trends that would almost inevitably lead to the further destabilisation of Pakistan’s already fragile political system.”

Pakistan’s gross tertiary enrolment (GER) ratio was only 13% in 2023, according to UNESCO. This is much lower than in India, and lower than in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka as well. Of 109 countries UNESCO profiled in 2021, Pakistan’s tertiary GER was 100th. Given Pakistan’s huge college-aged population, there is serious unmet demand for higher education.

There are currently 4.5 million Pakistani students in secondary education (grades 9–10), and 2.5 million in upper-secondary education (grades 11–12). More than 25 million children aged 5–16 are “out-of-school” (36% of the cohort’s total population, a proportion similar to that in Nigeria).

Far more girls than boys do not complete school for a range of factors, including poverty and traditional views about the role of women. The literacy rate is 68% for adult men and 46% for adult women.

Regional disparities and opportunities

A Pakistani student’s access to education depends greatly on their household income, gender, and region. Just over a third (36%) of the population lives in cities, where there is more wealth and literacy, and where more schools are considered “functional.” In the poorest areas, many schools lack running water, plumbing, and electricity.

In an excellent report published in 2024 focused on regional opportunities in Pakistan, the British Council considers that, at the city level:

“Lahore, Karachi, and Islamabad will continue to provide the bulk of outbound students simply because of their population size. Second-tier cities, however, are proliferating. Faisalabad is large and fast-growing. Peshawar has begun to emerge as the next major city for outbound students….

Second-tier smaller cities are also seeing strong growth in demand for study abroad, especially in the Punjab (Gujranwala, Sialkot, Gujrat, Multan). Their economic growth lies in their connection to the bigger metropolitan areas, with a four or five-hour drive seen as an acceptable connection time. Important and growing industries in these second-tier cities mean that families have money to pay for education. Hence, industry growth has been matched by rapidly growing education provision. Large private school networks are also spreading out from the major cities to the smaller ones. These feed students directly into higher education.”

Further, students prefer certain destinations depending on where they live in the country:

- “Punjab, the largest and most populated region in Pakistan, is the largest contributor to student mobility to the UK. The UK has consistently been the top study destination, mainly through strong family connections with many fourth-generation families having well-established businesses in UK cities. Many political and business leaders of Pakistan from the region have also studied in the UK.

- In Islamabad and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, students mainly choose between the UK, North America and Australia. Often, the UK is not the top destination choice.

- Pakistan’s south region has the smallest population and includes Karachi and a few smaller cities. Students from this region mainly choose the US as a study destination.”

Outbound mobility trends

Leading destinations are all recording significant increases in Pakistani enrolments, and demand is especially high for postgraduate studies. Successive governments of Pakistan have slashed educational budgets, and one implication has been the closure of many graduate programmes, which is driving outbound mobility at this level.

Recent data on which destinations are hosting the most Pakistani students include:

- UK: 34,690 in 2022/23 (+50% y-o-y)

- China: 28,000 before the pandemic

- UAE: 24,865 in 2020 according to UNESCO

- Australia: 23,380 in 2023 (+49%)

- US: 10,165 in 2022/23 (+16%)

- Germany: 8,210 in 2022/23 (+22%)

- Kyrgyzstan: 6,000 in 2020 according to UNESCO

- Malaysia: 5,000 in 2023

- Canada: 4,750 in 2023 (+101%)

- Turkey: 2,385 in 2020 according to UNESCO

- Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Sweden, Qatar: At least 4,000 in 2020 according to UNESCO

Malaysian institutions are currently recruiting intensively in Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia has been increasing its scholarships for Pakistani students.

Meanwhile, educators in Canada, the US, and UK understand that while Chinese and Indian demand for study abroad remains high, it can be easily disrupted by immigration policies and geopolitics. It is worth noting that:

- ApplyBoard found that January to June 2024, Pakistani student demand for the UK grew by over 30% compared to the same period in 2023.

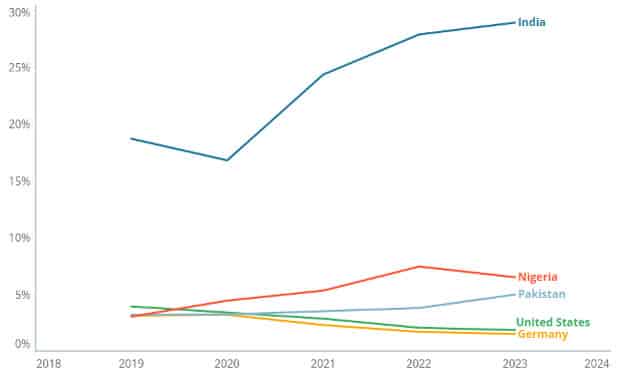

- Studyportals found that Pakistan was second only to India in terms of growth in demand for study abroad between 2022 and 2024 and that its share of enrolments, among the top-five student sending markets, is trending upward.

Transnational education

Thousands of Pakistanis are currently pursuing foreign degrees online, and they may soon be able to study for these degrees in-person in Pakistan. Pakistan’s Higher Education Commission (HEC) launched a revised transnational education policy in September 2024 that opens the door for foreign branch campuses. According to Times Higher Education:

“Under the policy, foreign institutions can offer degree programmes in Pakistan if they are among the 700 top-ranked universities in the world. There are also specific requirements around local contexts, with institutions required to ‘strictly comply with and respect the constitutional provisions, local laws, and the ideology of Pakistan.’”

The British Council reports that “HESA data show that 11,715 students in Pakistan are taking UK qualifications through transnational education, with most choosing distance and online models.”

Middle-class pressures

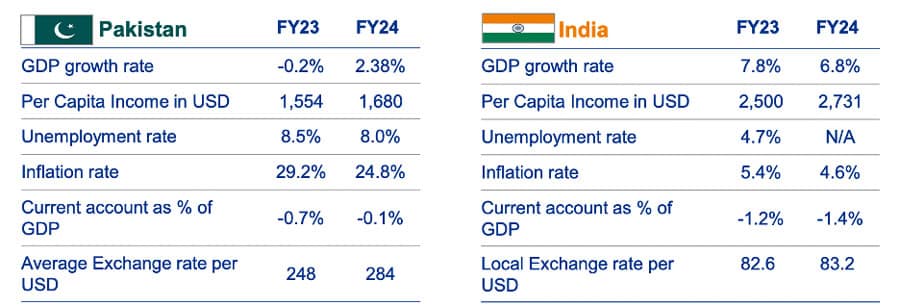

After slowing in 2023 (following devastating floods in 2022), the Pakistani economy has recovered somewhat, and the Pakistani rupee has stabilised a bit relative to the US dollar. The agricultural sector was the main reason for growth, up 6% in 2024 compared with overall GDP growth of 2.5%. But the situation remains difficult, as you can see in the following chart from KPMG comparing economic indicators in Pakistan and India in 2024 versus 2023.

A 2017 estimate by Pakistani market research firm Aftab Associates put 40% of Pakistanis in the middle class, up substantially from previous years. But this proportion may be shrinking.

The middle class is shaky and dynamic due to a lack of internal structural stability in the economy. Pakistan is incredibly dependent on loans and other packages from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and allies such as Saudi Arabia, UAE, and China. For the 24th time, the IMF approved a new loan in September 2024 in an “ongoing effort to strengthen macroeconomic stability, address deep structural challenges, and create conditions for a stronger, more inclusive, and resilient growth.”

In the meantime, Pakistanis are struggling due to persistently high inflation rates and currency fluctuations.

“The lower middle class has been really hit in the last few years,” Javaid Ghani, pro vice chancellor at Karachi’s Al Ghazali University, told the Wall Street Journal earlier this year. Many households “are struggling to hold on to the markers of a middle-class life as they are buffeted by higher food and energy prices.”

Pakistan’s independent newspaper, The Friday Times, featured an article in August 2024 that explained how current economic trends affect students aiming to study abroad:

“One of the primary challenges Pakistani students face in their quest to study abroad is financial affordability. Tuition fees, living expenses, and currency exchange rates often present insurmountable barriers for many Pakistani families because the value of the Pakistani Rupee has sunk to such depths that a single US dollar (August 7, 2024) costs around Rs278.5. Because of these circumstances, even the wealthiest people in Pakistan are forced to lead modest lives in developed countries. Managing spending becomes extremely challenging as the Pakistani currency’s value has diminished by more than 100%.”

When they undertake a cost analysis, Pakistani students find that overseas university tuition is surprisingly and excessively expensive. The ordinary Pakistani cannot afford the cost of international flights, rent, food, and transportation. In a developed foreign country, one can only purchase a cup of coffee with a monthly wage of Rs12,000 in Pakistan.”

As difficult as study abroad may be to afford, many families remain determined to secure a quality higher education for their children abroad, driven by a sense of hopelessness about opportunities in Pakistan. An Ipsos poll conducted in the summer of 2024 found that only 1 in 10 Pakistanis believe their country is headed in the right direction.

Muhammad Khan, a restaurant manager in the northern city of Rawalpindi who turns his fridge off in the day and works two jobs but who still cannot make ends meet, told the Wall Street Journal:

“The lower middle class, like us, is now just posing as white collar. Honestly, we are in the poor class now. Seeing the political situation, I have no hope.”

Private schools

Where there is hope, however, is in Pakistan’s thousands of private schools. These have ballooned from 3,000 in 1982 to 137,000+ in 2024. Almost half of Pakistani children attend private schools – many of them from lower-income households.

A fascinating study by researchers at Harvard explores what is behind the popularity of Pakistan’s for-profit, non-religious, fully autonomous private schools. It investigates why middle-class and poorer families are able to send their children to these schools, and finds:

“The key element in their rise is their low fees. They hire predominantly local, female, and moderately educated teachers who have limited alternative opportunities outside the village. Hiring these teachers at low cost allows the savings to be passed on to parents through low fees ….

At the time of writing, a typical private school in a village in Pakistan charged a fee of Rs. 1,000 per year (roughly $18). The countrywide data analyzed shows that fees are low for all the provinces in Pakistan, as well as within rural and urban regions within each province. The analysis shows that in rural areas, the median annual fee roughly translates to $1.50 a month, or less than—much less than a dime a day. Thus, these schools’ fees are affordable even for someone living at the dollar-a-day poverty line established as a global benchmark.”

The researchers also note that affordability does not mean lower quality:

“Despite lower levels of education and training, lower salaries in private schools do not imply lower educational quality. Because private schools are held accountable by parents, who may monitor teacher behavior and can withdraw their children if performance is poor, private schools have full incentives to hire the best available teachers who then exert high effort. Indeed, teacher absenteeism rates appear to be lower and student test scores higher in many private schools as compared to government schools.”

Government support for study abroad

The number of universities in Pakistan has been rising quickly, but quality is a major issue, as is government interference and underfunding. There are over 200 universities and 3,000 degree colleges (which are similar to community colleges) across the country.

To counter domestic higher education issues, the government supports study abroad, not least because personal remittances from Pakistanis abroad compose a significant portion of GDP (over 8% in 2022). The UN says. “The substantial share of remittances highlights the importance of the Pakistani migrant community abroad in the economic development and stability of the country.”

Key motivations for students

Pakistani students are first and foremost interested in accessing a high-quality foreign degree to enhance their career prospects. Affordability is a major concern – and so scholarships are much sought-after. Similarly, the ability to work during studies and post-study work opportunities can make the difference in decision-making about where to go.

Recommended reading

We highly recommend checking out the following resources:

WENR’s focus on Pakistan (2020), which includes assessment criteria and what official documents are recommended from Pakistani students.

The British Council’s 2023 report, Landscape of in-country funding options for students from Bangladesh, India and Pakistan to pursue higher education overseas.

The British Council’s 2024 report, Mapping international student mobility from Pakistan at the province / territory and city level.

For additional background, please see:

Source