The volume of Chinese students choosing to study abroad is rising and may even return to pre-pandemic levels in the next year, according to industry experts and data trends. But the nature of demand is changing due to the increasingly complex nature of this crucial sending market. While rankings and prestige still matter greatly to many Chinese students, other factors have risen in importance, including:

- Proximity and safety, which became top drivers of Chinese families’ choice of destination in the pandemic and which remain major priorities;

- Cost, in a context of high job insecurity in China and a faltering post-pandemic economic recovery;

- Employability outcomes, as youth unemployment remains a key problem in China.

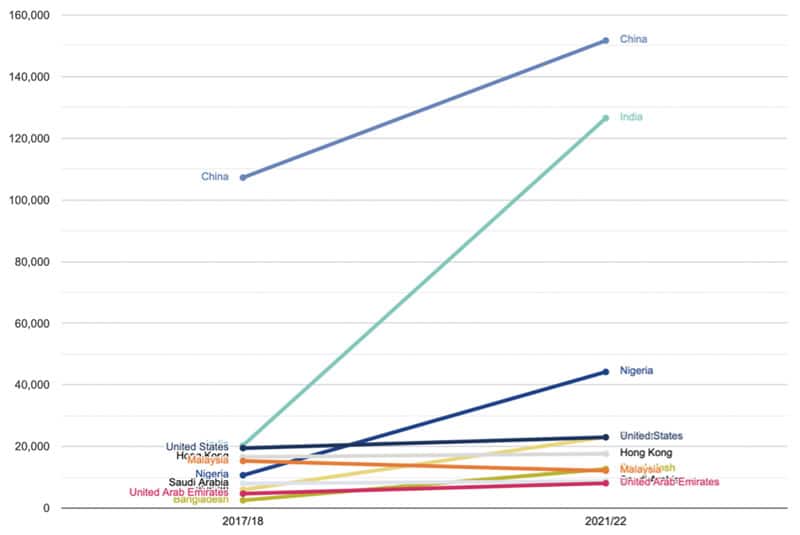

Three of the “Big Four” English-speaking destinations (Australia, the UK, and US) remain the most preferred options for study abroad and are the largest hosts of Chinese students:

- US: 289,530 (2022/23, 0% growth y-o-y)

- Australia: 166,420 (2023, +6.5% growth y-oy)

- UK: 151,675 (2021/22, +56% growth y-o-y)

But Asian destinations – especially Japan – as well as Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Thailand now command significant share of interest due to advantages such as proximity, affordability, and the presence of many highly ranked universities.

Asian destinations’ advantages shine even brighter in a year in which Australia, Canada, and the UK have more restrictive policies around international students – and leading into the November 2024 US presidential election. As it stands, former president Trump (whose platform is heavily premised on limiting immigration) has a very good chance of being elected for the second time. Recent research has found this prospect to be appealing, or at least a neutral proposition, for some prospective international students, but China/US tensions rose when Trump was president and families of prospective Chinese students will no doubt be aware of this.

Canada used to enrol many more Chinese students than it does now; enrolments are down about 40,000 since 2019. In 2023, Japan enrolled more Chinese students (115,495, +11% over 2022) than Canada did (101,150, +1% over 2022).

South Korea (68,065 in 2023, +6.5% y-o-y), Germany (42,580 in 2022/23, +9%) and Malaysia (39,010 in 2022) also host significant numbers of Chinese students. In 2023, Chinese applications to Malaysian institutions were up 21% compared with 2022 (to 26,630), and they have doubled since 2019.

Thailand is very popular among Chinese students looking for affordable education, and the number of Chinese students studying in Thailand has doubled within the past five years to over 20,000.

Otherwise, The China Daily reports that “Russia, Belarus, Italy, Ukraine, Ireland, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland have made it to the list of top 20 overseas education destinations for Chinese students.”

The ups and downs of destinations’ popularity

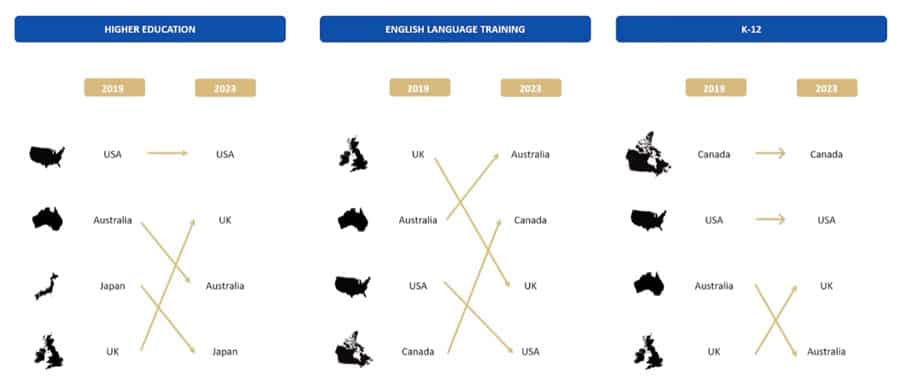

Viewers of a recent webinar hosted by international education industry research firm BONARD, Recruiting students from China, were presented with data showing that for Chinese students looking for university degrees, the UK has become much more popular in the past few years. In fact, UK universities are hosting more Chinese students now than in 2019. This means that the UK is the only destination other than Hong Kong to have exceeded its pre-pandemic volume of Chinese students. The US and Australia have recovered about 78% of their 2019 volume, while Canada has recovered 72%.

The US has held its ground in terms of its popularity among families of prospective Chinese students according to the BONARD graphic below, while Australia and Japan have lost some traction in the market. Canada is not even in the top four in 2023 for Chinese higher education students.

When we look at English-language training, however, it’s Australia and Canada that have gained students’ interest, while the UK has dropped to third. The Australian ELICOS sector’s increased share of demand may be short-lived, however, as visa rejection rates for Chinese English-language students have increased over the past year. While 97% of Chinese applications for Australian universities were approved as of June 2024, only 56% of Chinese ELICOS applicants receive a positive response to their visa application.

Sociologist Angela Lehmann, chair of the Foundation for Australian Studies in China, told Times Higher Education that in some Chinese circles, Australia’s more restrictive visa policies are being seen as “anti-China policy.” Declines in Chinese students in ELICOS could also have a debilitating effect down the line for Australia’s universities, as the higher education system relies to a significant degree on recruiting international students from ELICOS.

For families of K-12 students, Canada is the leader, as it was in 2019.

Chinese outbound set to surge – where will students go?

Speaking during the BONARD webinar, Mingze Sang, president of the Chinese agency association BOSSA, said the Chinese outbound student market recovered to about 80% in 2023, and he expected as many Chinese students will choose to study abroad in 2024 as before the pandemic. When polled, 13% of webinar attendees said they expected a major increase in Chinese student numbers in 2024 compared with 2023, 30% expected there will be more Chinese students, 34% expected stability in numbers, and 16% expected fewer Chinese students.

The UK is the only destination of the Big Four that has maintained its position – appeal-wise and in terms of enrolments – in the Chinese market. But even there, dynamics have changed: Mark Corver, managing director of data and analytics at the consultancy dataHE, says that lower-ranked UK universities are less able to compete in China than they once were – not least because elite UK universities are recruiting in China more aggressively than in the past, and also because there are a growing number of highly-ranked universities in Asia.

Elite US universities are having no issues maintaining Chinese enrolments – but other US institutions are facing a more price-sensitive student consumer in China, which is making it more difficult for many to recruit in the market. Writing in Inside Higher Ed, Xiaofeng Wan explained that there is a misconception about the ease with which Chinese families self-fund their children’s education abroad. The institution he works at, Amherst College, surveyed Chinese parents “to gain a deeper understanding of the current thinking among Chinese families on affording an American education.”

Mr Wan noted that of the 343 Chinese parents Amherst surveyed in in late June 2024, 90% intended to fully fund their children’s education in the US. But there is more to this story: many of those parents will be stretching their savings to afford their children’s education, and many could use scholarships/aid to be less pressured financially. Of the parents Amherst surveyed:

- 35% had an annual after-tax income between US$74,740 and US$149,481;

- 30% took home US$14,948 to US$74,739;

- 2% had an after-tax income below US$14,948.

That middle bracket – the 30% with annual after-tax income of US$14,948 to US$74,739 – will obviously find it challenging to afford a four-year American college programme. The 2% with incomes below US$15,000 will find it even more difficult.

But Chinese parents tend not to apply for aid because they believe it will reduce their children’s chances of admission. Mr Wan said their concerns are valid:

“There are only seven colleges in the United States that adopt a need-blind admission policy for both domestic and international applicants and that truly do not consider an international applicant’s ability to pay during the admission process— namely, Amherst, Bowdoin and Dartmouth Colleges; Harvard, Princeton and Yale Universities; and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.”

All this brings us back to the question of where Chinese students will go in the next couple of years for study abroad. If they can’t afford the UK or US, they may not choose Australia or Canada given policy changes in those countries and Canada’s generally declining appeal for Chinese families looking at higher education options abroad. (Study permits for Chinese students applying to Canadian institutions fell by 40% between 2018 and 2023).

Some observers have begun to parse the market by generation, where older generations remain strongly drawn to the Big Four destinations, and younger cohorts are much more interested in regional study destinations within Asia. That trend towards regional study seems to have been accelerated by the pandemic as greater numbers of Chinese students gained more experience with study destinations closer to home within Asia during those years.

Japan, Malaysia, Taiwan, and South Korea have all set ambitious new international enrolment targets, and there is no doubt their universities and schools are recruiting heavily in China right now. China is by far the top international student segment for Japan, Taiwan, Malaysia, Thailand, and South Korea.

Chinese more open to a range of destinations

Chinese students are not only becoming more interested in staying in Asia, but they are also open to whatever destination/institution best meets their needs – whether that’s through attractive pricing, cost-of-living, programmes, or, increasingly, internships.

Chinese youth unemployment rose dramatically through, and after, the pandemic, in tandem with slowing growth in China’s economy. The youth unemployment rate rose above 20% in June 2023, and soon after, the Chinese government suspended public reporting of this employment metric. Suffice to say that jobs are very much on the mind of Chinese students and families when they choose where to study. Su Su, senior project consultant at BONARD’s China branch, said in the BONARD Recruiting students from China webinar that:

“The so-called Return-On-Investment is a term I hear mentioned more and more by parents and students when planning overseas studies. Parents will consider affordability and employability when choosing a school and will appreciate internship opportunities in local companies.”

In 2021, a BOSSA survey of around 8,000 Chinese students found that nearly 30% of students said they would increase the number of countries they were applying to to ensure the stability of their study abroad plans. And China Institute of College Admission Counseling’s (China ICAC) 2023 Annual Report found that “58% of schools reported that over half of their students applied to colleges in multiple countries.”

Regional targeting is a must

Su Su said it’s imperative for institutions – wherever they are – to understand that Chinese families are strongly influenced by schools who spend the money to send a representative to where they live in China. She provided the example of a K-12 school in Switzerland that sent a representative to Zhengzhou (North China) to develop a strong rapport with parents there, and noted that within the span of 2 years, not only the school but also the destination of Switzerland became incredibly popular in Zhengzhou.

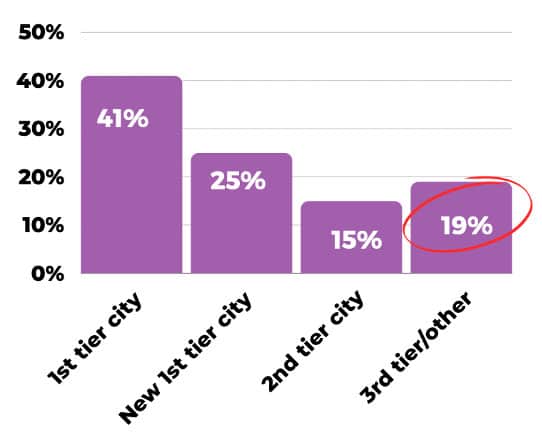

Ms Su used the Swiss school example to impress the importance of precise market targeting in China. It’s a huge country, and different programmes and destinations are more or less popular in certain regions, and lower “tier” cities hold great potential. (There are four city tiers in China based generally on economic prosperity: Tier I, New Tier I, Tier II, and Tier III.)

Edufair China notes:

“Tier I cities are saturated with recruitment from schools with well-established market footholds. Recruiting in second and third-tier cities means less competition from other foreign institutions for both agents and students. The further schools move from first-tier cities and markets, the more likely they’ll be to find students and agents eager to engage.”

Similarly, the survey informing China ICAC’s 2023 Annual Report secured participation from significantly more institutions in Tier III cities – “growing from 8% last year to 19% this year … indicating a growing interest and engagement [in international education] from a broader range of regions.” Overall, 111 institutions across China participated in the survey.

What’s more, lower-tier cities also hold the majority of China’s international schools, which offer excellent recruitment opportunities for foreign educators. Sunrise Education notes in its Trends in International Education and Student Mobility in 2024 report:

“Regionally, Tier 2 and 3 cities are home to 62.1% of China’s international schools. Tier 1 cities Beijing and Shanghai account for 11.2% and 11.9% respectively. Guangdong, which includes two Tier 1 cities as well as many Tier 2+ cities, accounted for 14.8%.”

In 2024, these are the cities categorised into four tiers (Tier I, New Tier I, Tier II, Tier III), as explained by Siam Commercial Bank (Thailand):

- “First-tier cities comprising Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen. Those are the most 4 developed cities in economics and infrastructures as people have high purchasing power. All are large cities that have political and cultural influence over the country.

- New first-tier cities comprising 15 cities; Chengdu, Hangzhou, Chongqing, Wuhan, Xi’an, Suzhou, Tianjin, Nanjing, Changsha, Zhengzhou, Dongguan, Qingdao, Shenyang, Hefei, and Foshan. All are big cities with high development in economics and infrastructures after the 4 First-tier cities. Consumers also have high purchasing power.

- Tier 2 cities comprising 30 cities and most are major county or on the east coast; Xiamen, Fuzhou, Wuxi, Kunming, Harbin, Jinan, Changchun, Wenzhou, Shijiazhuang, and Nanning, etc. All cities are not as booming as the new First-tier cities.

- Tier 3 cities comprising 63-71 cities (depending on the ranking person) which are as prosperous as the district level and are considered economically developed cities.”

Digital marketing tips

In China more than any source country, adapting digital marketing to the local market is key – on search platforms such as Baidu (aka “China’s Google”), which has a 70% share of the “traditional” search engine market, and on social media giant WeChat (estimated reach of over 1.3 billion monthly active users). In addition to Baidu, Sunrise Education says that using alternate discovery platforms in addition, such as Zhihu and Toutiao, can add a boost to marketing. You can check out Sunrise Education’s 2024 Trends in China’s Digital Landscape whitepaper here for more information.

Sekkei Digital Group advises:

“Transitioning or building your site means more than just simply translating it into Chinese. Your content will need to be equipped to cater to Chinese online habits. You can achieve this by considering website layout preferences, image preferences, and design choices. Localizing your site[2] will also improve its SEO ranking because most search engines in China favor a “.CN” domain name over foreign web pages. Through this, international applicants and other Chinese users can find your website easier when they look for international schools or exchange programmes.

On top of tailoring your website to the Chinese market standards and appearing on top of search engine results, remember that you need reputable web hosting services in China and an ICP licence.”

Sunrise Education says short-form videos remain exceptionally popular in China:

“Short-form video accounts are a useful new tool for recruitment in China. Douyin offers a robust advertiser backend, and Bilibili offers an opportunity to build an organic following as well as to run targeted digital campaigns. Douyin grew from a niche platform before the pandemic to having more than 731 million monthly active users (MAU) in 2022, while Bilibili has reached 341 million MAU. These platforms saw meteoric growth during the pandemic, but they’ve demonstrated staying power and reflect the broader global shift to short-form video like we’ve seen in the west with TikTok and Instagram Reels.”

Working harder is a must, and career supports are key

The British Council’s senior lead for culture and education, Joshua Gabriel, a panelist on the BONARD webinar Recruiting students from China, said:

“Parents and students are going to be looking more at employment outcomes and return on investment from study abroad, so employability is going to be a key push in 2024. Students are applying to multiple institutions, which means students have more choices. The appetite remains strong from China, but institutions around the world may need to work harder.”

Rona Wu, manager of ShinyWay International, concurred that employability is a major driver in 2024, saying that finding a job is a huge stress for Chinese students. BOSSA’s president Mingze Sang said that all educators need to realise that families are most concerned about jobs for their children, and career supports must be built into programmes if institutions want to be competitive in the Chinese market.

As for whether Asian destinations’ new popularity will prove a serious challenge for Western institutions recruiting in China, Mr Sang reminded the audience that destinations such as Singapore and Hong Kong are small and limited in terms of capacity. In this sense, their popularity may not have a profound effect in terms of share of the Chinese market.

Top Chinese students, however, are paying particular attention to the most highly ranked Asian institutions. Mr Gabriel pointed out that Hong Kong and Macao are attractive especially for their combination of high-quality education and safety.

Ms Wu says that a common tendency is for Chinese students to apply to a Western and an Asian institution, say in the UK and in Hong Kong, and then to compare their offers. Which is more highly ranked? Which is more affordable? Which offers internships?

In essence, Chinese students now know they have more choices, and their new habit of applying to institutions in multiple destinations is one worth keeping in mind as educators sharpen their recruiting strategies this year. The market still holds great opportunities, but it will take more to convince students that an institution is the best fit for them.

For additional background, please see:

Source