It is becoming increasingly clear that a decline in international enrolments is putting the finances of UK universities under great pressure this year, leaving many with no choice but to cut staff, eliminate courses, reduce research innovation, and even shut down whole departments. Some universities are facing financial pressures so dire that they are at risk of bankruptcy.

A prominent article in The Sunday Times last week highlighted to the UK public the virtually impossible challenge the country’s higher education sector now faces:

- Most universities will lose vital international student tuition in the 2024/25 academic year in part because the dependant’s ban (preventing most international students from bringing their partners and children with them to the UK) is depressing demand from key non-EU markets.

- At the same time, universities are losing on average £3,000 per domestic student they enrol, not least because of inflation. As The Financial Times (FT) explains, “inflation is driving up operating costs, including energy bills and salaries, while eroding the real-terms value of domestic tuition fees.”

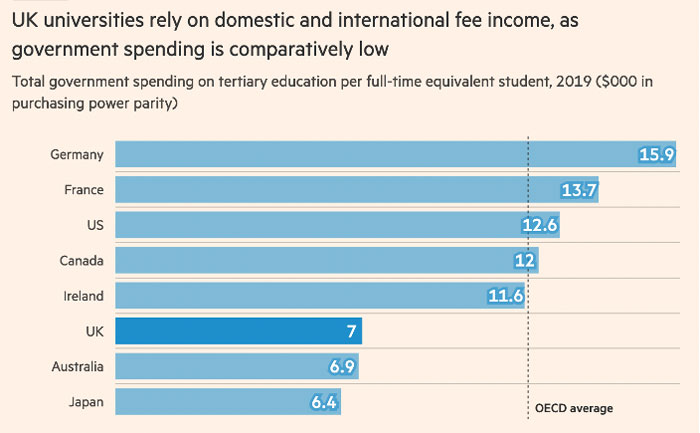

- The UK government spends less on public tertiary education than many advanced economies, including Canada, the US, Germany, Ireland, and France.

Over a third of UK universities are in trouble

The Sunday Times reports that 40% of England’s universities will run budget deficits this year and that closures and mergers are highly possible. The UK’s University and College Union (UCU) shared a list of 66 universities in financial distress in 2024 – a proportion that represents over a third of all universities in the UK. Many of those universities are having to lay off staff and eliminate courses – especially in the humanities and creative arts.

Jo Grady, UCU’s general secretary, wrote a letter to Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson and Skills Minister Jacqui Smith last week in which she stated:

“Anything short of an emergency rescue package for the sector will be insufficient to stave off catastrophe. This funding package should, though, come with conditions such as ensuring jobs are protected. We think there are three universities we have been able to identify that could be close to financial collapse and would benefit from state intervention and support. If they do not get state support they will struggle still and use cuts to staff as shock absorbers. We see this as a systemic crisis. We don’t think parents and prospective students understand the total mess some of our universities are in.”

At Goldsmiths University, half of the history and sociology department and a third of all English and creative writing academics are at risk of being laid off. The Sunday Times spoke with Michael Rosen, the former children’s laureate, whose position as professor of children’s literature was one being considered for redundancy (he has since learned he is “safe”), and Rosen commented:

“What’s happening at Goldsmiths is a disaster. Slashing the number of staff means whole courses are being closed down, and the essence of what Goldsmiths has offered in terms of diversity, is being wrecked. It’s heartbreaking.”

Why are universities in such dire straits?

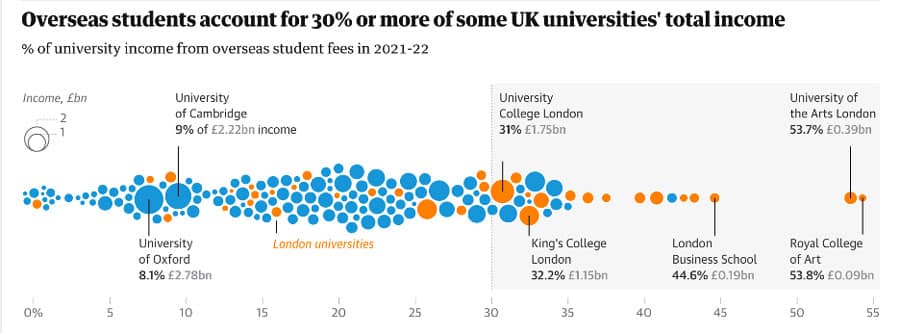

Since 2012, when the government under David Cameron raised undergraduate UK students’ tuition to £9,000 a year, domestic fees have risen by only £250 (to £9,250). As reported in FT, consultancy firm DataHE has calculated that “the £9,000 fee introduced in 2012 would now be more than £12,000 if it had increased in line with consumer prices … instead it is £9,250.” Universities have thus become increasingly reliant on international student tuition to cover costs. A Guardian analysis in 2023 found that “one in every five pounds received by UK universities last year came from international students.”

FT elaborates:

“International students, who typically pay about double the home fees, are the primary source of additional income enabling many universities to make ends meet. International fees account for nearly 20 per cent of universities’ income — up from about 10 per cent just over a decade ago. For a long time this money helped fund research, but it is now being diverted into making up the shortfall on domestic undergraduate tuition. At the same time, Brexit has cut off access to EU funding streams that were worth an aggregate average of £800mn a year to UK higher education institutions between 2010 and 2020, leaving the sector even more reliant on overseas students to balance the books.”

What’s more, the UK government spends much less than other leading economies on higher education, as shown in the chart below.

UK universities have thus become highly dependent on international students – especially those from non-EU countries. The following chart from the Guardian shows the extent to which some universities are dependent on foreign students’ income.

The dependant’s ban, introduced in summer 2023 and launched in January 2024, is seriously affecting the ability of many UK universities to recruit in key non-EU markets (including Nigeria, the third-largest source market), thus imperiling their ability to operate.

There has been a 49% decline in Nigerian students’ applications to UK universities for the upcoming academic year according to June 2024 UCAS data. Nigerian students have been especially drawn to one-year master’s programmes in the UK, and these programmes are now subject to the dependant’s ban.

The situation is worse for postgraduate taught courses (also included in the dependant’s ban). The number of international students applying for such courses at Russell Group universities (24 leading universities in the country) starting this September have declined by 10%. Tim Bradshaw, chief executive of the Russell Group, warned former Prime Minister Rishi Sunak – who was mulling the prospect of scrapping the UK’s popular Graduate (work rights) Route – that if the applications decline led to a similar drop in enrolments, “it would cost our group £500 million in lost income.”

The Russell Group aside, a survey by the British Universities’ International Liaison has determined that “the drop in applications is nearly three times bigger across the sector as a whole.”

Vivienne Stern, chief executive of Universities UK, said in an LBC interview earlier this month:

“With costs rising and income for teaching falling as a result of frozen tuition fees, we need the government to recognise that this cannot be left to drift. If we want our universities to be amongst the best in the world, as they currently are, we need to do something to stop the deterioration in their finances.”

For its part, the newly elected Labour government in the UK has been quick to signal that it will continue to look to international revenue to bolster funding for the sector. Speaking to BBC this week, new Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson said, “We want to make sure we are putting universities on a more sustainable footing overall. And part of that is what we see, for example, around international students, who are an important part of our system—not just in economic terms, what they contribute, but also in our reach around the world and our soft power.”

Worries about research funding in Australia

Australian universities are also reeling from the Australian government’s decision to massively hike visa application fees (which are non-refundable) and begin capping international student numbers in 2025. Australia, like the UK and Canada, is losing share of international students’ interest in the wake of these announcements.

Writing in Times Higher Education in July 2024, John Carroll, director of the Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute and dean of biomedical sciences at Monash University, warned:

“The direct causal relationship between international student revenue and research support was brutally exposed by the pandemic, as borders were closed and overseas enrolments plummeted. Are memories really that short? We are still recovering from that trough in revenue: deficits remain in most research-intensive universities, but the bigger impact has been the year-on-year savings targets and cost-saving measures needed to keep the books balanced. This is undermining risk-taking, creative endeavour and innovation.

It is also sapping the morale of researchers. For many of them, getting out of bed every day has become harder. And with the proposed visa restrictions making Australia the least likely destination for the world’s smartest students and researchers, they now go to bed worried about whether the resources will be in place to allow them to do their best work and, quite frankly, keep their jobs secure.”

For additional background, please see:

Source