Holy Confessor Bishop Ambrose (before monasticism, Alexander Alexeyevich Polyansky) was born on November 12, 1878, in the village of Petelino, Elatma County, Tambov Province, to the family of a priest. The Polyansky family had many priests in their line, and they were known for their strong Christian piety. Alexander received his primary education in the parish school in his hometown. When he was nine years old, his father sent him to study at a religious school in the city of Shatsk, Tambov Province. He continued his education at the Tambov Theological Seminary, graduating in 1899. In the same year, he entered the Kazan Theological Academy.

Holy Confessor Bishop Ambrose (before monasticism, Alexander Alexeyevich Polyansky) was born on November 12, 1878, in the village of Petelino, Elatma County, Tambov Province, to the family of a priest. The Polyansky family had many priests in their line, and they were known for their strong Christian piety. Alexander received his primary education in the parish school in his hometown. When he was nine years old, his father sent him to study at a religious school in the city of Shatsk, Tambov Province. He continued his education at the Tambov Theological Seminary, graduating in 1899. In the same year, he entered the Kazan Theological Academy.

In 1901, he took monastic vows with the name Ambrose and was ordained as a deacon. In 1902, he was ordained as a priest. In 1903, Father Ambrose graduated from the academy with a degree in theology and was appointed as a teacher at the Kiev Theological Seminary. He was also assigned to the brotherhood of the Kiev Caves Lavra. In 1905, he was awarded the pectoral cross. In 1906, he was appointed as the rector of the same seminary and elevated to the rank of archimandrite.

Revolutionary riots and moral degradation in society also affected the Theological Seminary, despite the rector’s best efforts. On March 29, 1907, a revolt erupted among the students, driven by their dissatisfaction with the evaluation of their behavior over the last quarter. The disorderly conduct involved whistling, making noise, shouting, and the stomping of feet directed at the members of the inspection present during lunch and dinner when the disturbances occurred. After evening prayers, despite repeated warnings from the rector and the inspector, the disturbances continued, particularly in the form of loud whistling, noise, and offensive outbursts, which lasted continuously for about two hours. The lights in the corridor where all of this was taking place were extinguished. Items like spittoons, lampshades, pieces of plaster, and even classroom boards appeared on the scene.

At midnight, a delegation that came to the rector presented the following demands: 1) more humane treatment of the students by the inspection; 2) a review of behavior grades, changing the grades from four to five; 3) the reinstatement of dismissed students, and 4) immunity for the delegates’ personal safety. The demands were not accepted. The next day, whistling resumed before classes; occasional whistles and shouts were heard between the lessons, which escalated the general disorder. On March 30, an emergency meeting of the educational assembly decided to suspend classes and send the students home.

Despite such disheartening occurrences, which indicate how the spirit of the times had permeated young people in the church, Fr. Ambrose was actively involved in assisting financially disadvantaged students. He was a permanent member of the Society for the Assistance of Needy Students of the Kiev-Podolsk Theological Seminary and served as the chairman of the council of the Petropavlovsk Trusteeship for poorly supported students of the Kiev Theological Seminary. In 1915, in recognition of his diligent service at his diocesan obediences, Archimandrite Ambrose was awarded the Order of Saint Vladimir, 3rd class.

Archimandrite Ambrose was known for his deep piety and humility, and he was beloved by both the students of the seminary and by the ecclesiastical authorities, particularly by Metropolitan Flavian of Kiev and Galicia (Gorodetsky). On several occasions, there were discussions about consecrating Archimandrite Ambrose a bishop, but Metropolitan Flavian, who highly valued the devout monk and zealous worker in the field of preparing young men for service to the Church, would only say, “I need him.” Metropolitan Flavian himself was a missionary, an ascetic, and a man known for his exceptional charity; he never refused anyone material assistance. In Kiev, he designated specific days for meeting with the needy, and people gathered in the morning to receive his generous contributions. Being a devout man himself, he valued piety in his associates.

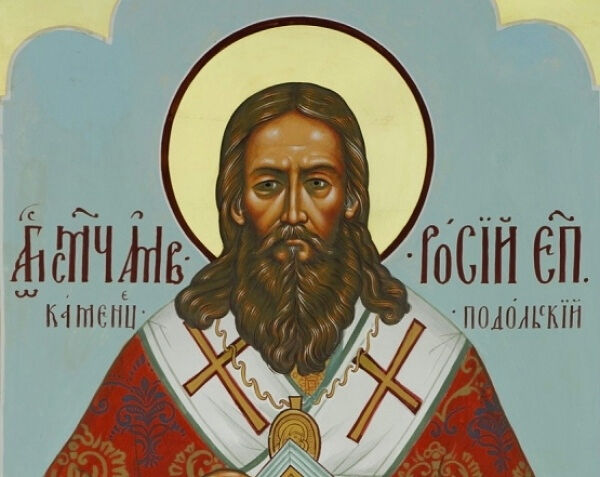

On October 22, 1918, Archimandrite Ambrose was consecrated as the Bishop of Vinnitsa, serving as the vicar of the Kamenets-Podolsky Diocese. In 1922, he was transferred to the Kamenets-Podolsky and Bratslav Diocese, but his time there was relatively short.

After the end of the civil war in Ukraine and the emergence of the Soviet government, harsh measures were taken against the Orthodox Church. The renovationist Archbishop of the Kamenets-Podolsky Diocese, Pimen (Pegov), invited Bishop Ambrose to join the renovationist organization. However, the Saintly Bishop declined, which the renovationists reported to the OGPU (the predecessor of the KGB), leading to his arrest. He was falsely accused of supposedly sheltering former officers of the Tsarist army by ordaining them as priests. The accusation was baseless, as the individuals in question had long retired from military service and were working as teachers. Having chosen martyric path awaiting them under the soviet regime, they passed an examination for the priesthood and were ordained by Bishop Ambrose.

In 1923, Bishop Ambrose was exiled from Ukraine and he settled in Moscow. Following the expulsion of the Orthodox hierarch from the Kamenets-Podolsky Diocese, with the support of Soviet authorities, the renovationists completely devastated it. For instance, in Vinnitsa, there was not a single Orthodox church left.

In 1923, the renovationists entered into negotiations with the Russian Orthodox Church regarding terms of reunification. Their primary condition was the removal of Patriarch Tikhon from Church administration and his retirement. At the end of September 1923, a meeting of twenty-seven hierarchs was held at the Donskoy Monastery to discuss matters related to reconciliation with the renovationists. Reports were presented by Archbishops Seraphim (Alexandrov),  The Life of Holy Hieromartyr Hilarion (Troitsky), Archbishop of VereyOne of the most eminent figures of the Russian Orthodox Church in the 1920s was Archbishop Hilarion of Verey, an outstanding theologian and extremely talented individual. Throughout his life he burned with great love for the Church of Christ, right up to his martyric death for her sake. His literary works are distinguished by their strictly ecclesiastical content and his tireless struggle against scholasticism, specifically Latinism, which had been influencing the Russian Church from the time of Metropolitan Peter Moghila [of Kiev].

The Life of Holy Hieromartyr Hilarion (Troitsky), Archbishop of VereyOne of the most eminent figures of the Russian Orthodox Church in the 1920s was Archbishop Hilarion of Verey, an outstanding theologian and extremely talented individual. Throughout his life he burned with great love for the Church of Christ, right up to his martyric death for her sake. His literary works are distinguished by their strictly ecclesiastical content and his tireless struggle against scholasticism, specifically Latinism, which had been influencing the Russian Church from the time of Metropolitan Peter Moghila [of Kiev].

“>Hilarion (Troitsky), and Tikhon (Obolensky).

Archbishop Seraphim was the first to speak: “Godly-wise shepherds, acting as three delegates of  Patriarch Tikhon

Patriarch Tikhon

“>His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon, we have just now held a thorough discussion with His Eminence Metropolitan Evdokim regarding the question of the liquidation of our ecclesiastical division. His Eminence Metropolitan Evdokim proposed that we immediately discuss three questions concerning this matter… The first question is whether we agree to reconciliation with him. If we agree, then we need to establish communication and begin joint preparatory work for the upcoming Local Council. In this case, the Local Council will be convened by His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon. At this Council, Patriarch Tikhon must relinquish the administration of the Church and retire. If we agree to carry this out, His Eminence Evdokim has given us the assurance that Patriarch Tikhon will be reinstated to his current rank at the Council.”

Photo: pravlife.org Bishop Ambrose responded to the essence of Archbishop Seraphim’s report: “I am surprised, your Eminence, that you refer to Evdokim as His Eminence,” he said. “Do you recognize him as the legitimate hierarch?” Archbishop Seraphim replied that he did, but he agreed that his decision on this matter was not straightforward. “But for me, and probably for others present here, Evdokim is not at all His Eminence, but a former archbishop, because he joined the schismatics (self-proclaimed clergy who separated from His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon and, according to their ideology, from the Church of Christ). Consider for yourselves, who were the leaders among them? Former Archbishop Antonin, who is now retired at the Zaikonospassky Monastery. He opposed Patriarch Tikhon out of personal motives, and others with dubious pasts joined him. Antonin turned out to be a blasphemer. As we know, he opposes the veneration of God’s saints and acknowledges only the Holy Trinity and sacred events from the life of Christ and the Mother of God. He refers to the iconostasis as an unnecessary partition that should be torn down. Bishop Leonid is not well-known to us, but he is undoubtedly compromised in order to undermine the canonical principles of Holy Orthodoxy. Vvedensky, a former priest from Petrograd, is now a married bishop, is basically a member of the Jewish community. Priest Boyarsky expressed blasphemous views at their unlawful Council against the veneration of the relics of the saints. These corrupt individuals rebelled against His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon and holy Orthodoxy. Archbishop Evdokim joined them and, by doing so, renounced the Church of Christ. Therefore, he cannot be a legitimate bishop.”

Photo: pravlife.org Bishop Ambrose responded to the essence of Archbishop Seraphim’s report: “I am surprised, your Eminence, that you refer to Evdokim as His Eminence,” he said. “Do you recognize him as the legitimate hierarch?” Archbishop Seraphim replied that he did, but he agreed that his decision on this matter was not straightforward. “But for me, and probably for others present here, Evdokim is not at all His Eminence, but a former archbishop, because he joined the schismatics (self-proclaimed clergy who separated from His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon and, according to their ideology, from the Church of Christ). Consider for yourselves, who were the leaders among them? Former Archbishop Antonin, who is now retired at the Zaikonospassky Monastery. He opposed Patriarch Tikhon out of personal motives, and others with dubious pasts joined him. Antonin turned out to be a blasphemer. As we know, he opposes the veneration of God’s saints and acknowledges only the Holy Trinity and sacred events from the life of Christ and the Mother of God. He refers to the iconostasis as an unnecessary partition that should be torn down. Bishop Leonid is not well-known to us, but he is undoubtedly compromised in order to undermine the canonical principles of Holy Orthodoxy. Vvedensky, a former priest from Petrograd, is now a married bishop, is basically a member of the Jewish community. Priest Boyarsky expressed blasphemous views at their unlawful Council against the veneration of the relics of the saints. These corrupt individuals rebelled against His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon and holy Orthodoxy. Archbishop Evdokim joined them and, by doing so, renounced the Church of Christ. Therefore, he cannot be a legitimate bishop.”

After discussing the question of reconciliation and unity with the renovationists, a closed vote was held, in which the majority of the bishops expressed their opposition to such a move.

A year later, Bishop Ambrose was arrested again. He was held in custody by the OGPU for ten days. Upon his release, he served in various churches in Moscow, regularly delivering sermons during worship services. In 1925, Bishop Ambrose was appointed as the administrator of the Kamenets-Podolsky Diocese, but he had no possibility of travelling there. At the end of November 1925, all the bishops who were assisting the Locum Tenens of the Patriarchal Throne in managing the Russian Orthodox Church were arrested in Moscow. Bishop Ambrose was arrested with them. The interrogations were conducted by Tuchkov and Kazansky.1

The first interrogation protocol was recorded half a month later, on December 16, 1925.

“In which church or monastery do you primarily serve?” the investigator asked.

“At the Danilov Monastery,” Bishop Ambrose replied.

“Whom among the bishops living in or near the Danilov Monastery and serving there do you know?”

“I know Bishops Damaskin, Parfeniy, German, and Ioasaf; Archbishops Pakhomiy and Prokopiy.”

By that time, all of them had been arrested along with Bishop Ambrose and were detained in the inner prison of the OGPU or in the Butyrka Prison.

The second interrogation protocol was drawn up on the Feast of the Meeting of the Lord, February 15. The investigator, relying on the testimonies of informants, inquired about the content of the bishop’s sermons in the churches.

Bishop Ambrose responded, “In my sermons, I speak on purely ecclesiastical and moral topics, avoiding any societal elements. I did not specially deliver sermons on the theme, ‘All rulers are ruled by God,’ but I did touch upon the text in my sermons. I interpreted it as meaning that everything on Earth occurs by the will of God, and if there are calamities and misfortunes, whether in the lives of individuals or nations, it is solely the punishment of God for their sins, intended for their correction. Regarding these punishments on nations, I referred to the post-revolutionary famine, without specifying dates or particular events, using terms like ‘shortage of provisions’ and ‘general need,’ generally discussing ‘severe trials’ in life in a broad sense.”

As for my stance on the  The October Revolution: Prophecies on Russia’s DestinyWhy is this subject so important to us (and we must understand that it is of very serious importance to us) who may have nothing to do with Russians or Russia? Those who have ears to hear, let them hear; and those who have eyes to see, let them see.

The October Revolution: Prophecies on Russia’s DestinyWhy is this subject so important to us (and we must understand that it is of very serious importance to us) who may have nothing to do with Russians or Russia? Those who have ears to hear, let them hear; and those who have eyes to see, let them see.

“>revolution, I have never expressed my thoughts and convictions on this matter in my sermons. Personally, I consider the revolution as God’s judgment upon all classes of the Russian people for their past actions.

I reiterate that I have never touched upon political events in a specific manner and have not given any reason to interpret my views on the revolution differently from what I have already stated. Perhaps people misunderstood me in this way without any grounds on my part, or maybe they did not understand me; I do not know.”

The next interrogation took place a month and a half later, on March 29. By this time, Tuchkov and the 6th OGPU department had already formulated their judgment, resolving that the bishops residing in the Danilov Monastery constituted an illegal Synod under Metropolitan Peter. Therefore, any meetings of these bishops in the monastery and any discussions of church matters were viewed as discussions of pressing church issues by the Synod. When asked whether the bishops’ meetings were sessions of the Synod under the Locum Tenens of the Patriarchal Throne, Bishop Ambrose responded, “In the Danilov Monastery, we had discussions on various church matters to exchange opinions, but the views expressed in these discussions were not binding on anyone. There were quite a few such issues, and it’s difficult to remember them all.”

After returning to his cell following the interrogation, the bishop began to recall the details of the questioning, particularly the zeal and desire with which the interrogators sought to reinterpret and distort the meaning of every word, aiming to ascribe a political character to church decisions and actions. What in the bishop’s view was purely a church action necessitated by ecclesiastical canons compiled and recorded hundreds of years ago, long before Soviet authority existed, took on a political significance in the interrogator’s eyes, with far-reaching implications. In response to this, the bishop decided to provide an explanation.

The next day after the interrogation, he sent a statement through the prison department’s secretary of the OGPU to the interrogator. He wrote, “Regarding the interrogation on March 29, I consider it necessary to state the following: For me, the Church is a religious community, and, like any community, it has its own laws and rules. Furthermore, the Church is a Divine institution with Divine rules at the core of its life, as expressed in Holy Scripture and the canons of Ecumenical and Local Councils. Anyone who wishes to belong to the Church must obey its rules and laws; otherwise, they depart from the Church, even if they outwardly appear to belong to it. Moreover, a clergyman must adhere to the laws and rules of the Church.

“I have embraced the spiritual life, become a servant of the Church, and I wish to continue belonging to it. Therefore, I strive to adhere to the laws and rules of the Church, and I view all events in the Church’s life solely from the perspective of Church rules and regulations, not from any other perspective, for example a political perspective. For example, I do not acknowledge the Renovationist movement solely because it violated Church laws (they are self-appointed, have married bishops, and so on). I acknowledge the Patriarchate solely, because it, not the Synod, is a canonical institution, as this exists in Eastern Churches.”

Regarding politics, I have never aspired to it and do not aspire to it. My soul is not inclined toward it. In the past, I was not involved in politics, did not participate in any organizations or societies, and now, under Soviet rule, I do not engage in politics. I do not belong to any organizations or societies, nor do I participate in any political activities, nor have I committed any crimes against Soviet authority.”

Bishop Ambrose was sentenced to three years of imprisonment and sent with Archbishop Prokopy (Titov) of Kherson to the Solovki Concentration Camp. On November 30, 1928, the bishops were informed that they would be exiled to the Ural region after serving their camp sentences. They traveled together via Ekaterinburg and Tobolsk. On April 7, during the Annunciation holiday, they arrived at the Tobolsk isolation chamber and were released on the same day. However, their freedom was short-lived, as they were re-arrested on April 9 and placed in the Tobolsk Prison, where they spent one and a half months. As soon as the river navigation season began, they were transported by the first steamboat to the town of Obdorsk. After a month, Bishop Ambrose was sent from there to the small village of Shuryshkary, where he remained until July 5, 1931, at which time he was returned to Obdorsk.

Photo: fond.ru On July 30, 1931, Bishop Ambrose and Archbishop Prokopy were arrested again. The true reason for their arrest was these saints’ profound faith, their unwillingness to compromise, their lifestyle in remote exile, and the fact that they dared to celebrate the Divine Liturgy even in exile, albeit with only a few people in attendance. Their correspondence with Metropolitan Peter, who was in the far north as the Patriarchal Locum Tenens, also irritated the godless authorities.

Photo: fond.ru On July 30, 1931, Bishop Ambrose and Archbishop Prokopy were arrested again. The true reason for their arrest was these saints’ profound faith, their unwillingness to compromise, their lifestyle in remote exile, and the fact that they dared to celebrate the Divine Liturgy even in exile, albeit with only a few people in attendance. Their correspondence with Metropolitan Peter, who was in the far north as the Patriarchal Locum Tenens, also irritated the godless authorities.

The decision to arrest them was made in Moscow, and therefore, witness interrogations and the search for charges began after their arrest.

The daughter of the church warden, Antonina Rocheva, testified: “Last year, when there were rumors amongst the population that they would close the church, Polyansky told my mother and my father, ‘They are going to close and desecrate the church. You shouldn’t let them close it, or you’ll all become atheists, and God will punish you. If you don’t agree, they won’t close the church forcibly.’ I spoke at the meeting in favor of keeping the church open. I did it because I was afraid of becoming an atheist. My father, the church warden, also opposed closing the church. My father… worked to keep the church open, collected money, and as a result, he was fined 150 rubles. When my father received the court’s verdict, Polyansky came to our house and said, ‘You have been unfairly condemned by the local authorities; file an appeal, and you will be acquitted.’ He also said, ‘The newspapers are writing that there won’t be any consumer goods, but there will be bread, although it will be expensive. You need to stock up a little at a time, or else you’ll go hungry. Everything is getting worse. Life was better before, and now there’s nothing left.’ Polyansky organized religious services, which local Zyryan women attended. I saw Maria Dyachkova and an old exile named Terenti Zhupikov praying at his services.”

Terenti Zhupikov, who lived in the same house as Bishop Ambrose, was summoned to the OGPU, where he stated: “In the village of Shuryshkary, he (Bishop Ambrose) has settled. He knows everyone, has become close with the Zyryan and Ostyak people. He visits the homes of each Zyryan, and some of them visit him. Ostyak people often visit him, providing him with fish, fat, and other things he needs. He does not engage in discussions with them because they do not understand each other’s language, but he is friendly with them. He told me and my comrade Sergienko, ‘Now is the time of persecution against the Church, believers, and clergy. The authorities are now exiling people because they are believers and refuse to close churches, and they don’t want to become atheists. Everywhere churches are being forcibly closed under pressure from the government. Once the churches are closed, it’s clear that people will become non-believers. Clergy are being exiled for serving the Church, with no other crimes committed. They exiled me, and I don’t know why. Others don’t know why they were exiled either. They arrested an elderly woman from our village in Kherson. Presumably, because she is a believer and sent me packages.’ He asked me and Sergienko why we were exiled and how long we had been in exile. I told him I was arrested in January 1930 and exiled along with a fellow villager. He told me, ‘They exiled you because of collectivization. Apparently, people didn’t want to join the collective farm. To intimidate the others, they took you and arrested you, and the rest joined the collective farm.’ He frequently tried to convince us of the truth of the Russian Orthodox Church and always criticized the sectarians, calling them charlatans and deceivers.”

The Head of the Organizational Bureau of OKRIK, Konev, stated, “Bishop Polyansky, upon his arrival in the village of Shuryshkary, had a close connection with Rechev and Dyachkov… Their connection was based on the fact that Polyansky frequently visited their apartments, and they also visited him. I cannot say exactly what kind of conversations they had… upon Polyansky’s arrival, the above-named individuals became the most knowledgeable in religious matters. Moreover, I personally saw prayer texts written on paper with a pencil by Dyachkov’s children. I believe this is also Polyansky’s doing, as Dyachkov and his wife are illiterate. All of these individuals strongly opposed the closure of the church… In addition, they all collected money illegally for the church’s upkeep, for which they were convicted. Once, in the spring of 1930, probably in May, Polyansky came to register with the Shuryshkary Village Council, where he began a conversation on religious topics first with the Village Council Secretary Karpov… and then I intervened in their conversation. Polyansky vigorously argued that ‘God exists and is real… He exists, and everything depends on Him…’ From this, I conclude that if Polyansky talks this way in the village council, he certainly does not hesitate to conduct such work among the unenlightened Zyryans and native masses.”

However, there was not enough evidence for the accusations. They introduced informants into the cell with the bishops, and one of them reported that Bishop Ambrose had said that every time he was summoned for questioning by the OGPU representative, he was offered to become an agent of the OGPU. “But I will never stoop to such treachery,” said Bishop Ambrose.

Summoned for questioning, the bishop insisted on writing his statements by hand. He held the word in high regard, especially the word of a bishop, and did not want any changes to be made to his testimony by the atheistic investigator. The bishop wrote, “I explain my arrest and expulsion from Ukraine by the fact that I did not join the renovationist organization, as suggested to me by the then Archbishop of the Podolsk Diocese, Pimen. I saw his report, as well as the report of a former comrade of the Chairman of the Supreme Church Administration of the renovationists, after my arrest in the local OGPU. Based on these reports, questions were posed to me. Based on this fact and others, I have the impression that the renovationist organization is in more a favorable position with the authorities than the Old Believers are. As for the motives and reasons for this favorable attitude of the authorities towards the renovationist organization, it is not for me to decide this issue; it is a matter for the authorities. Presumably, I can say that this may be due to the fact that the renovationist organization appears to be suitable and perhaps beneficial to the authorities, taking into account the reports of renovationist activists that I saw in the OGPU, as well as the fact that the renovationists violate church laws and rules, build church life according to their own will, and create divisions in church life, which may be favorable for the authorities that have set themselves the task of combating faith and the Church…”

In September 1931, the “case” of the archbishop was concluded. In the accusatory statement, the authorized representative of the Yamal Department of the OGPU wrote: “The Yamal Regional OGPU received information that the administratively exiled bishops Polyansky and Titov, while in exile in the village of Muzhi in 1929, established extensive connections with the local Zyryan and native Ostyak population… by conducting conversations on religious topics, giving them an anti-Soviet bias… organized illegal religious services in people’s homes and conducted overtly anti-Soviet agitation.

“Subsequently, the authorized representatives of the OGPU relocated Polyansky to Shuryshkary, and Titov to the village of Kievat, where they continued the same activities, exerting a harmful influence on the surrounding indigenous population. As a result, individuals in close contact with them began actively opposing the measures implemented by the Soviet authorities, such as the closure of churches, collectivization, the distribution of lands, and so on.

“During their interrogations as defendants, Polyansky and Titov did not admit guilt in the above-mentioned crimes and vehemently denied engaging in anti-Soviet agitation. However, taking into account that the existence of such activities was corroborated by witness testimonies, the OGPU decided to forward the case materials “to the Troika of the OGPU for the Urals for extrajudicial consideration.”

After the conclusion of the investigation, the bishops were sent to Tobolsk Prison. On December 14, 1931, a Special Meeting at the OGPU Collegium sentenced Bishop Amvrosy and Archbishop Prokopiy to three years of exile in Kazakhstan.

Bishop Amvrosy was sent to exile in the city of Turkestan, where he arrived in early September 1932. During this time, many exiled nuns from Russia, including those from the Sts. Martha and Mary Convent [in Moscow], lived in the area. One of the convent’s novices, Euphrosinia Zhurilo, took Bishop Amvrosy in. The OGPU authorities had told the bishop that he would have to travel 120 kilometers, crossing the desert to a small village named Suzak, where his place of residence was assigned. The journey involved a narrow and hazardous road, with sections running along the cliffs, where camels sometimes fell off the trail into the abyss. Novice Euphrosinia went to the head of the OGPU to plead with him not to send the bishop on such a distant and perilous journey and to allow him to stay in the city. However, her request was denied.

In the evening, the bishop talked with the nuns and novices from the Sts. Martha and Mary Convent. The next morning, they began packing his belongings and preparing him for departure. They gathered everything needed, arranged a cart, loaded his things, and handed him letters addressed to an exiled doctor they knew from Saint Petersburg and to the exiled nuns. They placed the bishop in the cart, and with tears in their eyes, they bid farewell to the confessor. The journey under the scorching sun took a toll on the bishop, and he barely made it to the place of exile. Upon arrival, he was immediately admitted to the hospital. However, his health deteriorated to such an extent that, despite the efforts of the doctor and nurses, the bishop passed away a week later, on December 7/20, 1932.

He was canonized among the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Orthodox Church at the Jubilee Hierarchical Council in August 2000 for universal veneration.