Editor’s note: The following piece draws heavily on commentary and insights from industry leaders speaking at the ICEF Monitor Global Summit in London, 23 September 2024.

International student mobility has historically been concentrated among the “Big Four” destinations of the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia. Over the past several years, however, there has been a shift towards a wider field of study destinations. That change is being driven both by changing student preferences and by the strategic goals, demographics, and labour market needs of emerging destinations.

New research from INTO University Partnerships shows that prospective students are applying to more programmes than ever before – typically four or five – and to more institutions in more destinations than in previous years. This trend is projected to continue in the long term, and it means that institutions investing in enquiry responsiveness and admissions processing will see more applications converting into enrolments. Destinations in which universities are climbing global rankings – e.g., China – will also see more conversions.

Students’ openness to alternatives reflects their changing priorities, including :

- Affordability;

- Fast visa processing;

- Geographic and cultural proximity;

- The expansion of English-taught degree programmes in non-English-speaking countries;

- Opportunities to work during and after studies in the host country.

At the same time, destinations such as Japan and South Korea are working more actively to recruit foreign students in part because of declining domestic populations of college-aged students and the related need to attract talent in key areas of local labour market demand.

“As international students seek to understand what return they can expect on their investments, we see that decisions across every major source market are increasingly based on cost,” says Peter Thompson, vice president of data analytics at INTO University Partnerships. For Jessica Turner, chief executive officer of QS, this creates a competitive point of differentiation for emerging study destinations: “In contrast to students seeking education in the Big Four, students setting their sights elsewhere tend to prioritise affordability over reputation and teaching credentials.”

Economic opportunities are a common draw

Dr Florian Hummel, vice-rector for international affairs at the International University of Applied Sciences (IU) in Germany, says, “The economy is one of the main reasons international students come to Germany. Our strong career prospects and clear post-study work rights are some of the reasons that a growing number of students from the Indian subcontinent are choosing to study at IU.”

A mix of factors drives choice

Cost of living influences many students, but more expensive destinations can still compete to significant market segments by virtue of other attributes. Living costs in Japan are relatively high, for example, but Japan welcomed an additional 50,000 international students in 2023 compared to the year before.

More students are also taking sustainability, national sentiment toward international students, and mental health into account when making their decisions. These issues are key areas of focus across emerging markets, and they could already be contributing to increases in student mobility to destinations such as Germany, France, and Finland.

Pros and cons

Greater access to a more diverse range of study abroad opportunities is good news for students. But Mr Thompson cautions that higher volumes of applications can also pose a risk to the sector’s reputation globally. For one, administrative functions will be under more pressure. And students may also delay decisions as they hedge their bets across destinations. This means that, more than ever before, speedy and effective response to enquiries and applications will be absolutely key.

Competing for foreign talent

Countries outside of the Big Four are seizing the opportunities of a changing international education landscape, with destinations across Asia and Europe growing in popularity. Ms Turner notes, for example, that the number of international students in China doubled over 10 years from 2013 and remains healthy despite declines in the pandemic. Further, with a healthy contingent of those students coming from other Asian countries, China continues to establish itself as an important player in intra-regional recruitment.

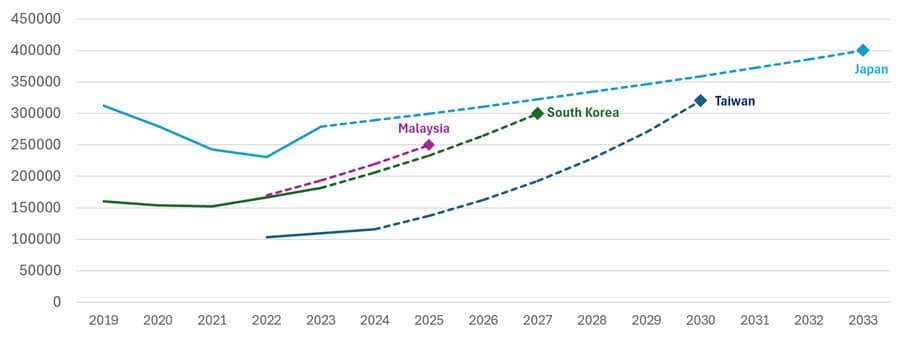

Japan, Malaysia, South Korea, and Taiwan are on upward trajectories as well, with Japan aiming to host 400,000 international students within the next decade. South Korea’s Deputy Prime Minister and Education Minister Lee Ju-ho declared last year that, “Now is the time to attract foreign talent strategically.”

In Germany, the government is the primary funder of the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD). Recognising the long-term benefits of global collaboration and welcoming the brightest minds, the DAAD is the world’s largest funding organisation for international exchange of students and researchers. In China, the government issues tens of thousands of scholarships for international students each year and is investing in infrastructure through initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative.

More English language programmes outside the Big Four

Edwin van Rest, chief executive officer of Studyportals, says, “The European Union’s decade of growth in this area is winding down. Now we are entering a decade of Asian expansion. South Asia has expanded its ETPs more than twofold since 2019. China, the Middle East and North Africa, and the rest of Asia have doubled their offerings. The Big Four are losing market share, dropping to 78% this year from 82% in 2021.”

That said, the English language is and will remain influential in Europe. Leaders such as Dr Hummel, are investing in ETPs as part of their growth strategies. One of Germany’s largest universities, the IU has approximately 200 programmes. Nearly half of those programmes are now offered in English or German.

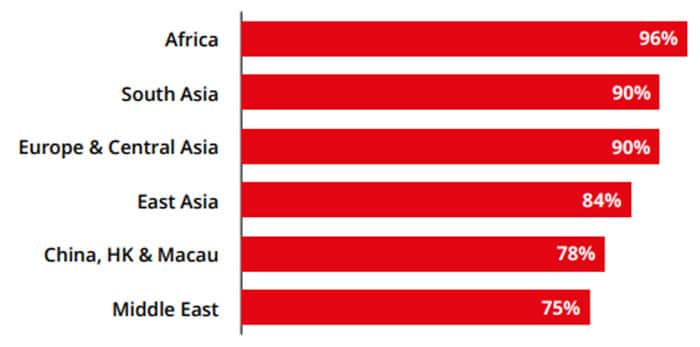

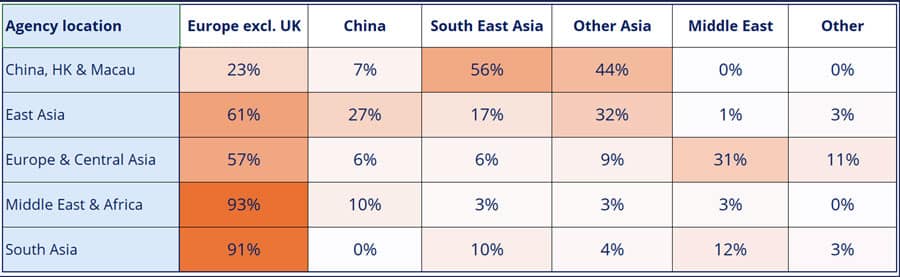

Indeed, educators across Europe are buoyant. France and Germany each enrolled more than 400,000 students last year and international strategies in Spain are generating results. The prospects of European institutions beyond the UK are extremely healthy overall: these destinations have become more attractive to international students from all major source countries in the last year. As we see in the table below, education agents report interest in these European destinations has surged more than 90% among students from South Asia, and the Middle East and Africa.

Agents in China, Hong Kong, and Macau also report that interest in non-UK European institutions has increased nearly a quarter. However, these agents have seen even greater growth in the appeal of institutions in Southeast Asia and the rest of Asia.

Policy drives students to alternatives

Mr van Rest says that many students from sending countries that are the most affected by new policy settings in Big Four destinations are now looking elsewhere: “What they find are more attractive conditions in terms of work rights, affordability, and proximity.” This may partly account for the dramatic surge in interest in New Zealand and Ireland this year: student applications to these countries via QS increased 7.2-fold and 1.7-fold respectively, compared to last year.

Flexible delivery modes disperse demand

New strategic approaches to international education in emerging markets demonstrate the global interconnectedness of the sector, which is ever more visible through expanded transnational education (TNE) activity, including regional hubs, remote delivery, and branch campuses. The UK dominates TNE, accounting for 75% of the market with around 580,000 students enrolled. Australia and the US are also key players, particularly in Asia and the Middle East. As a host country and as an education exporter, China is rapidly expanding its TNE offering and is becoming an increasingly influential player in the field.

Student mobility beyond the Big Four is being defined by strategies to deliver practical outcomes and relevant experiences. As the executive director and chief executive officer of NAFSA: Association of International Educators, Dr Fanta Aw, says, “There is plenty of room in a growing space. We should be thinking about the 20 major countries instead of the Big Four, because students should have choices to get the best education that is right for them.”

For additional background, please see:

Source