Venice is a city founded in A.D. 421 that exists entirely on water, whose streets and alleys have hardly changed in centuries, and is navigated either on foot or by little boats called vaporettos that zip along the canals.

It’s as if a tiny corner of the world had been dipped in resin around the turn of the 16th century and has been slowly, picturesquely deteriorating ever since.

Whole libraries have been written about its history, buildings, art, palace intrigues, and near hallucinatory effect on visitors.

So I didn’t pretend to myself that in the recent week I spent there I could do more than scratch the barest surface. I spent my days walking, people-watching, and visiting museums, churches, and the Biennale.

The weather’s lovely — very much like Southern California. Perching on the edge of canals, at the base of statues, on steps, ledges, and fountains is perfectly acceptable. Food is always close at hand: around every corner is a cafe, trattoria, pizzeria, or counter selling bread, pastries, dried meats, cheese, and cold limonatas.

Everything is stylish to within an inch of its life: haircuts, the gaily striped poles marking private gondola stops, museum tickets. The clothes, of softly draped linen, gabardine, cashmere.

Even the collection receptacles at the San Marco Cathedral Mass were stylish!: of deep red velvet, a kind of rectangular purse with a slit on top, like something in which you might deliver a letter to the pope.

For the most part I avoided the super-congested squares and streets (though if you’re visiting the justifiably famous top churches and museums, crowds are inevitable).

Venetians, whose city we’ve overrun, clearly resent us tourists. Over the course of the week I nonetheless developed a great sympathy for my fellow citizens of the world who, after all, had suited up and showed up and, like me, were doing the best they could.

Doing the best we could, we hit the high points. Titian was nearly 90 when he painted the “Pièta,” (1575-1576), housed at the crème de la crème of Venetian art: the Gallerie dell’Accademia.

A self-portrait with the artist as a stand-in for Nicodemus, the follower of Jesus who helped bury his body after the crucifixion, it was his last work of art.

In “Last Light: How Six Great Artists Made Old Age a Time of Triumph” (Simon & Schuster, $35), author Richard Lacayo observes that as Titian grew older, “the surfaces of his canvases became a mélange of splodges and ripples — and yet, out of them flesh, air, space and light still somehow emerged. The face of Mary Magdalene in the ‘Pièta’ was not much more than a mass of careless-looking dabs and daubs; yet there she was, alive and passionately grieving.”

Titian had wanted the painting to decorate his tomb, but he never finished. He died during a plague and is buried at the Basilica St. Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, more commonly known as the Frari, beneath a simple headstone.

The “Pièta” was completed by another artist and eventually brought to the Accademia. There I sat for several minutes, drinking it in. Perhaps the older we are the more we identify with Nicodemus — and with Titian: on our knees half-naked before the crucified Christ: supplicating, wondering, grieving.

I visited the Tintorettos at the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, too, and the Veroneses at the church of San Sebastiano, and the Chiesa di San Vidal, where I heard a Vivaldi concert one night.

But it was another Titian that clutched my heart: his recently restored “Assunta” (1515-1518) at the Frari.

Dominating the high altar, Mary, in a rose-red robe and a rich blue cloak, is being borne heavenward by choirs of cherubic angels. The upturned faces of the crowd below, the outstretched hands, the Blessed Virgin’s own beseeching eyes: all speak of the consummation of her original yes to the angel Gabriel.

The painting embodies our collective human plea: for a protectress, a guardian, a mother. “Take us with you!” the straining horde seemed to cry.

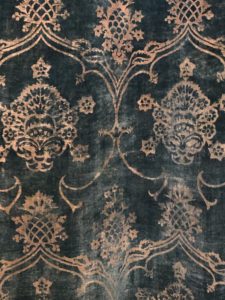

The Museo Fortuny, one of Venice’s innumerable smaller attractions, was another highlight. Mariano Fortuny (1871-1949), an eccentric artist given to wearing rich silk dressings gowns and turbans, lived in a palace, now the museum, that is draped ceiling to floor with rich panels of the fabulous textiles he designed.

With all that the real Venice, one intuits, is hidden behind high walls, closed shutters and locked doors.

That includes some of the storefronts: Antica Legatoria Piazzesi, for example, just off San Marco Square.

The handwritten signs on the door were priceless. “Hours: OPEN RARELY.”

Don’t touch anything, they continued, don’t sit on my steps, don’t drop food all over everything, don’t come in if you’re “just looking.” Donations welcome.

I finally found the delightfully irascible proprietor in one morning. The cramped and cluttered space — which claims to be Italy’s oldest paper shop — was not a store, she emphasized, but rather a studio; an atelier.

She wouldn’t let me touch anything but instead laid out a few stacks of notebooks from which I selected two, along with an irresistible pencil (10 euro) wrapped in marbled blue-green paper which obviously I can never use as at some point it would need to be sharpened.

Maybe the greatest aspect of travel is that you’re not sitting in front of a laptop or phone all day. I returned changed in ways I haven’t yet plumbed.

And again, massive thanks to the Venice-loving Angelus reader who underwrote my trip.