In a new study by the University of Cincinnati, scientists described a giant sea creature called a Japanese mosasaur. This creature was as giant as a great white shark and lived in the Pacific Ocean around 72 million years ago.

Scientists found this mosasaur in Wakayama Prefecture in Japan. They named it the Wakayama Soryu, which means blue dragon. In Japanese stories, dragons are legendary creatures.

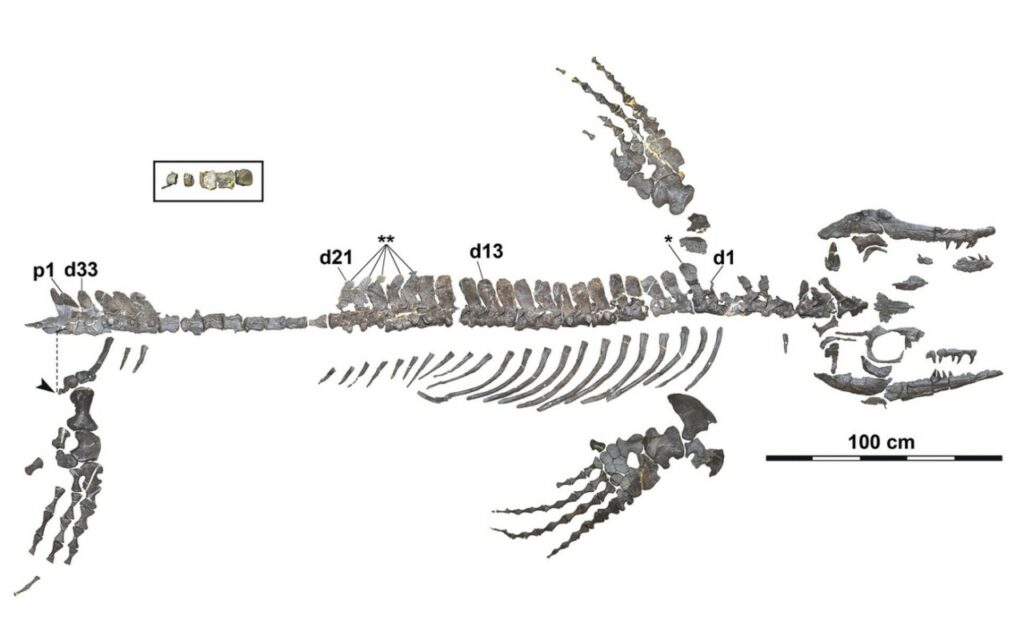

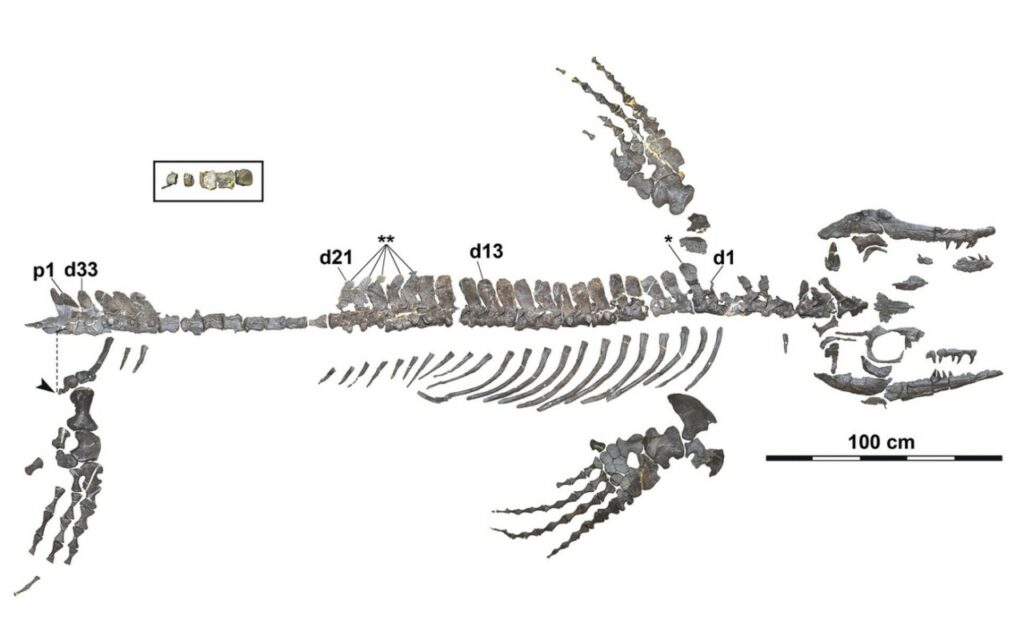

The scientists found this unique sea creature along the Aridagawa River in Wakayama, Japan, in 2006. One of the researchers, Akihiro Misaki, was looking for fossils of ammonites, a type of invertebrate, when he stumbled upon an interesting dark fossil in the sandstone.

Even though Misaki was focused on finding ammonites, he couldn’t resist looking at the dark bone he found. To his surprise, it turned out to be a vertebra, a part of the backbone belonging to a mosasaur. This discovery was fascinating because the mosasaur was almost entirely preserved in the hard sandstone.

This specimen is the most complete skeleton of a mosasaur ever discovered in Japan or the northwestern Pacific.

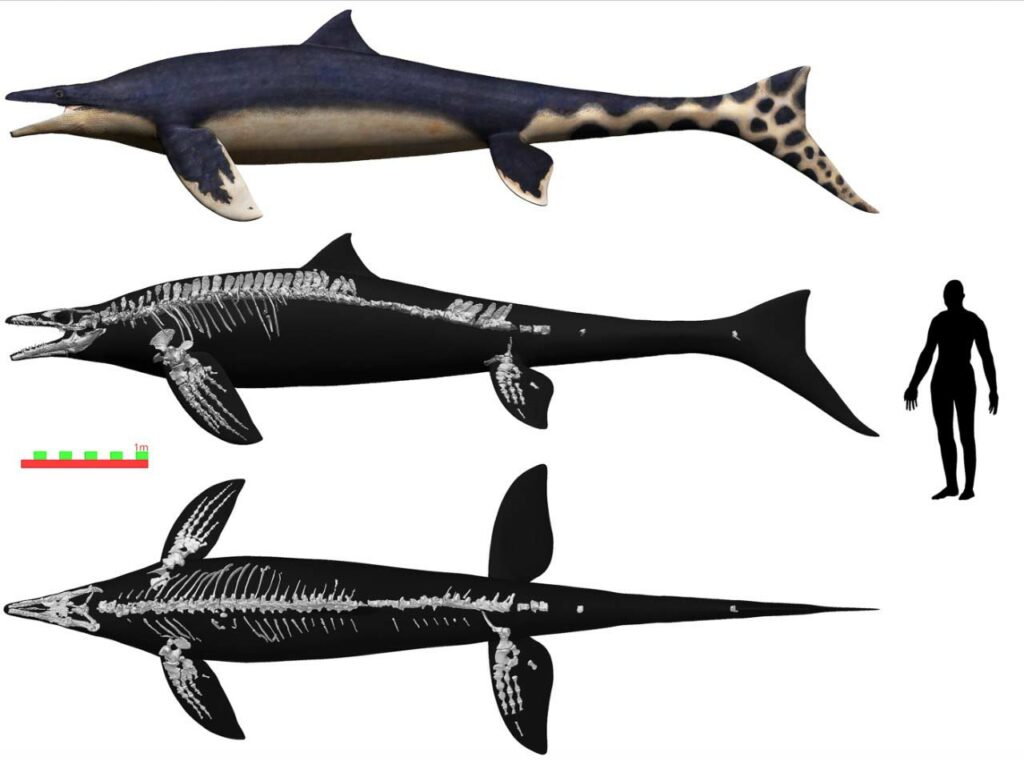

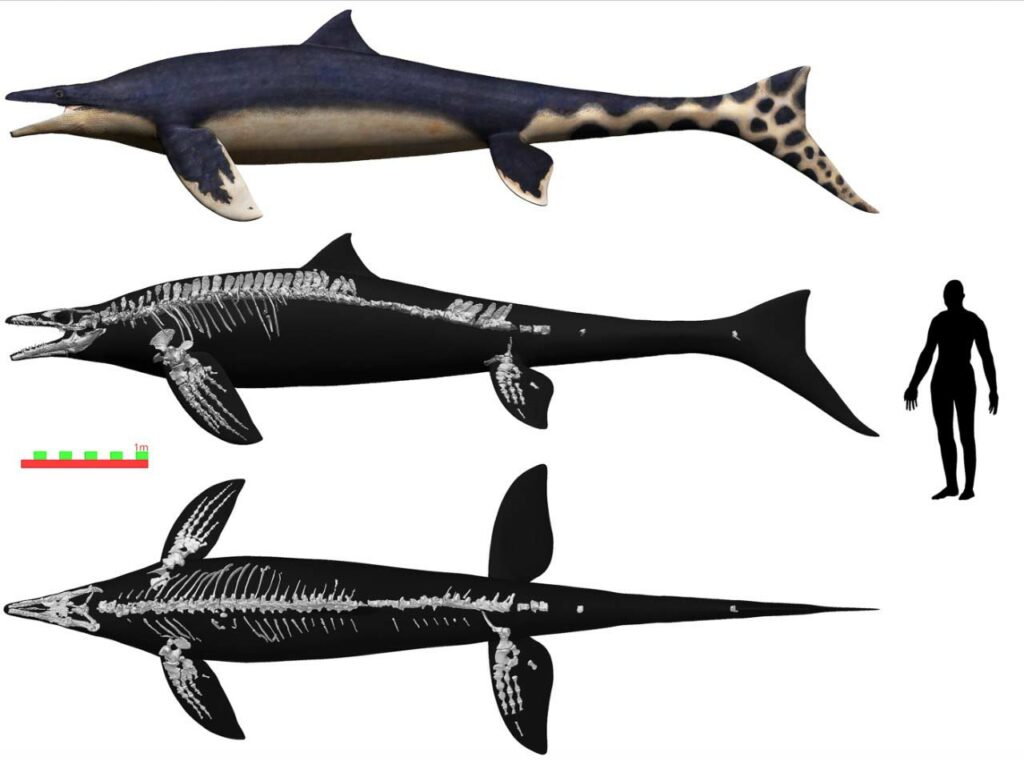

This special mosasaur had long back flippers that helped it move through the water and a long tail with fins. What makes it different from other sea creatures is that it has a fin on its back, just like a shark. This fin would have helped it turn quickly and move precisely in the water.

Its rear flippers are longer than its front ones. These enormous flippers are even longer than their crocodile-like head, unique among mosasaurs.

In the oceans of prehistory, mosasaurs ruled supremely from roughly 100 million to 66 million years ago. They lived in the same era as Tyrannosaurus rex and other dominant late Cretaceous dinosaurs on Earth. When an asteroid struck what is now the Gulf of Mexico millions of years ago, it caused a catastrophic extinction that wiped off nearly all dinosaurs, including mosasaurs.

The Wakayama Soryu mosasaur shares characteristics with mosasaurs discovered in New Zealand and California. It possessed almost binocular vision, a trait that would have made it a highly effective and deadly hunter.

Scientists classified this specimen within the subfamily Mosasaurinae and named it Megapterygius wakayamaensis, acknowledging its discovery location. The name Megapterygius means “large winged,” referring to the mosasaur’s massive flippers.

University of Cincinnati Associate Professor Takuya Konishi said, “Those big paddle-shaped flippers might have been used for locomotion. But that type of swimming would be extraordinary among mosasaurs and virtually all other animals.”

“Another prehistoric marine reptile called the plesiosaur used its paddle fins for propulsion, but it didn’t have a long rudderlike tail.”

“We lack any modern analog with this body morphology — from fish to penguins to sea turtles. None has four large flippers they use in conjunction with a tail fin.”

The scientists think that the Wakayama Soryu Mosasaur used its big front fins to change direction quickly in the water. The large rear fins might have helped it tilt downward or upward when diving or surfacing. Like other mosasaurs, its tail was likely used for swift and decisive movements, allowing it to accelerate quickly as it hunted for fish.

Konishi said, “How all five of these hydrodynamic surfaces were used is a question. Which were for steering? Which is for propulsion? It opens a whole can of worms that challenges our understanding of how mosasaurs swim.”

The Wakayama Soryu mosasaur was unique among mosasaurs because it seems to have had a dorsal fin. Scientists came to this conclusion by examining the orientation of the neural spines along its vertebrae. Interestingly, the way these spines were positioned is quite similar to that of a harbor porpoise, a marine mammal with a noticeable dorsal fin, as noted in the study.

While it’s still somewhat speculative, the distinct change in the orientation of these neural spines, especially behind a presumed center of gravity, aligns with what is observed in modern toothed whales, such as dolphins and porpoises, which have prominent dorsal fins.

Scientists took five years to remove the surrounding matrix of sandstone from the fossils. They also took a cast of the mosasaur in place to provide a record of the skeletal orientation of the bones before they were excavated.

Journal Reference:

- Takuya Konishi, Masaaki Ohara, Akihiro Misaki, Hiroshige Matsuoka, Hallie P. Street &Michael W. Caldwell. A new derived mosasaurine (Squamata: Mosasaurinae) from south-western Japan reveals unexpected postcranial diversity among hydropedal mosasaurs. The Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. DOI: 10.1080/14772019.2023.2277921